Copyright 2021 by Fred Pearce

North American edition first published by Greystone Books in 2022 Originally published in Great Britain by Granta Books in 2021

22 23 24 25 26 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a license from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright license, visit accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Greystone Books Ltd.

greystonebooks.com

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-1-77164-940-7 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-77164-941-4 (epub)

Copy editing for North American edition by Paula Ayer

Proofreading by Jennifer Stewart

Jacket and text design by Belle Wuthrich

Jacket illustration by Shutterstock/Nosyrevy

Background photograph by Adrian Pingstone

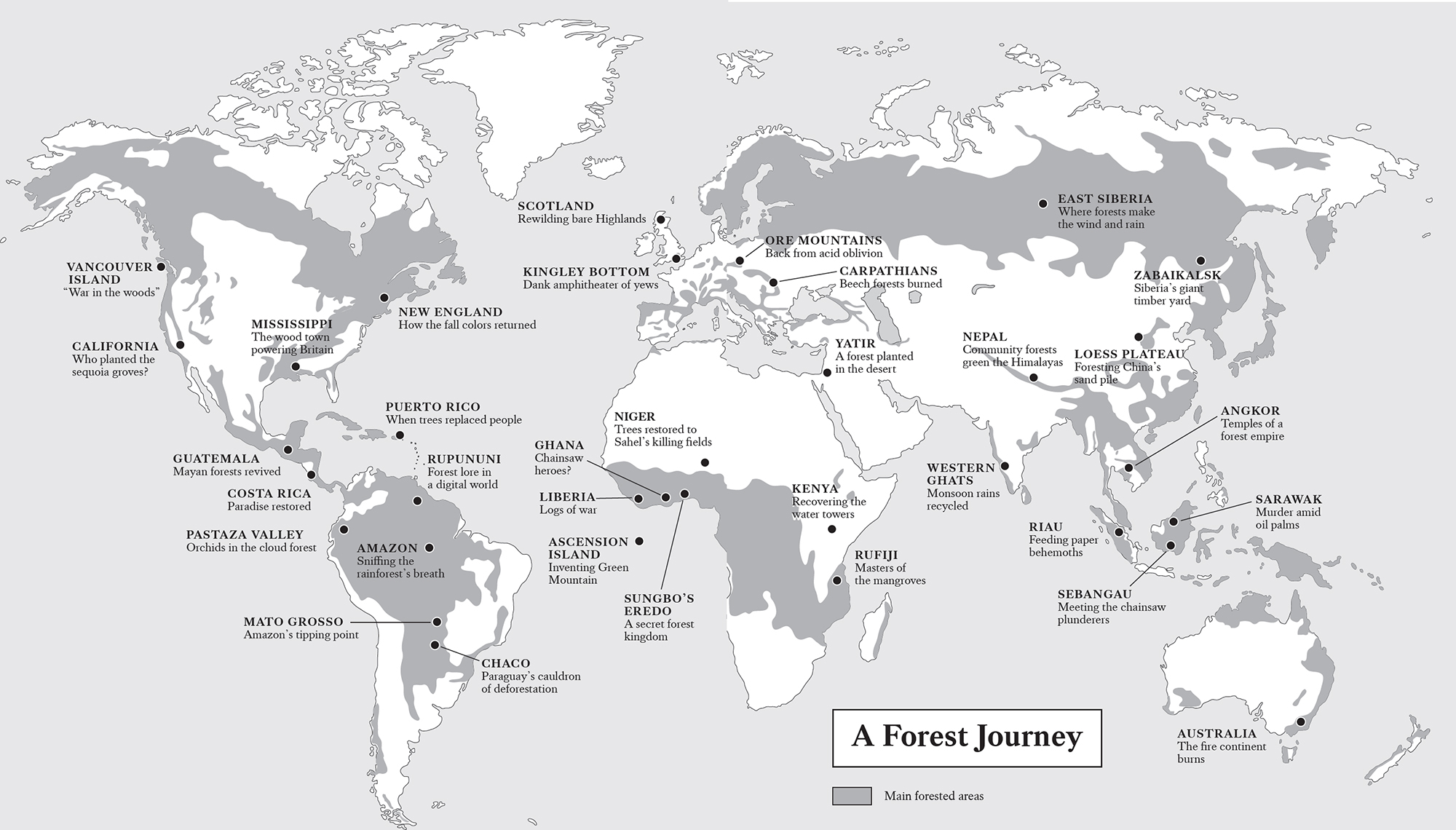

Maps John Gilkes

Greystone Books gratefully acknowledges the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples on whose land our Vancouver head office is located.

Greystone Books thanks the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit, and the Government of Canada for supporting our publishing activities.

To the memories of Don Hinrichsen and Conrad Gorinsky, pioneers both

Contents

IntroductionMyth and Magic

MY FIRST REAL EXPERIENCE of the wonder of tropical forests came in the Andean Mountains of Ecuador. It had been a long drive from Quito and evening was drawing on as we climbed into forests shrouded in cloudsclouds whose coverage was so extensive and permanent that no cartographers had ever mapped the terrain, and no satellites had ever observed the surface beneath. Breathing the sopping-wet air and peering into the gloom, I could understand why people occasionally showed up here believing that the trees hid an El Dorado of gold buried by the Inca half a millennium ago.

But I hadnt come for gold. Walking the next morning into the eternal mists above the valley town of Baos, I met Lou Jost. An American botanical explorer, he had come here to uncover his own El Dorado: a biological trove of orchids found nowhere else. He said his discoveries were changing our understanding of how and why plants evolve to create species that are unique to particular places, and why forests contain so much of the worlds biodiversity.

When I met him, Jost had already spent six years exploring the ridges around Baos. He operated alone, without the help of any academic body, having given up work as a quantum physicist in the US to pursue his dream. He said he found scouring the cloud forests for orchids more mind-expanding than the wonders of the universe. Quantum physics offered nothing you could touch and feel, he told me. But as soon as I visited a cloud forest, I was hooked. On the wet, sunless forest floor, species of orchids have evolved in the thin air with flowers so fragile that they would collapse anywhere else. He had already discovered ninety previously unknown orchids, and believed there were more here than anywhere else in the world. He had become an artist too, drawing and painting his discoveries.

The Pastaza valley, where Baos is situated, is the deepest and straightest valley in the eastern Andes, draining down into the vast basin of the Amazon River to the east. Despite being virtually on the equator, it is bone-chillingly cold and wet, and riddled with cliffs and ravines that are all the more dangerous in the permanent cloud. Not many people pass this way. The infrequent trails are mostly made by the mountain tapirs and spectacled bears.

The outside world intervenes, nonetheless. Every day a wind blows in from the Amazon rainforest, bringing huge volumes of moisture that condenses to form the near-permanent clouds. Each ridge catches the winds a little differently and has a different micro-climate, said Jost. Each species seems to specialize in a particular combination of rain, mist, wind and temperature. Some species grow by the thousand on top of a single ridge, but disappear just a few feet below and are found nowhere else.

The only way to discover the botanical secrets of these forests is to walk them all, Jost told me. Many of the hills have never been visited by scientists. Well, almost never. Jost came originally to follow in the footsteps of his hero, English botanist Richard Spruce, who trekked through the Pastaza valley in the 1850s, discovering ferns and liverworts that have never been seen since. The valley is comparable to Ecuadors other, more famous biological treasure house, the Galpagos Islands. On one red-letter day, Jost found four new species in a single patch of moss, raising the number of known orchid species of the genus Teagueia from six to ten. Since then, he has identified more of the distinctive long-creeping orchids here. One, Teagueia jostii, bears his name.

Josts orchid collection had become a life-consuming passion. His apartment in Baos was strewn with plant samples. A tiny rooftop greenhouse grew plants collected on past expeditions. Many had only opened their petals under his tender care. You have to know what you are looking for when you go orchid hunting, he says. The flowers are only a few millimeters across and usually hide under the leaves. Often the plants are not in flower. If I spot what I think is a new species, I can often only be sure when I bring it back here to wait for the flower to appear.

Their survival in Josts apartment looked precarious. He kept the greenhouse air mountain-cool with an electric fan, which depended on the towns fitful power supply. As a backup, he had a passive air conditioner that drew in air over permanently wet tiles. There was an ingenious device to maintain humidity, using a paperweight balance. When a packet of plant stalks on the balance became too dry, it lost weight and the balance shifted, switching on a humidifier. Once moist again, it switched the humidifier off. Its not perfect. But it means I can go away on plant-collecting expeditions and be fairly sure my specimens will still be alive when I return, he said.

Can Josts wild orchid El Dorado survive? The value of the Baos cloud forests biological heritage is increasingly being acknowledged. In 2006, near a waterfall just down the valley from Baos, Jost and local officials erected a bust to commemorate Spruces journey there. Jost, a loner when I visited him, is becoming a celebrity himself. He now runs the EcoMinga Foundation, an NGO dedicated to protecting Ecuadors upland ecosystems. In 2016, TV naturalist David Attenborough launched a film about Jost and the orchids of Baos.