Contents

Guide

A DDITIONAL P RAISE FOR T HE J OURNEYS OF T REES

A handful of seeds is all it takes to launch a new forest. Should we do it? Zach St. George chases the answer to this vital question from California to New Zealand in this smart and engaging book that illuminates the past and explores possible futures.

Kim Todd, author of Tinkering with Eden

In the rings of trees, we can see the past. Zach St. George brilliantly reports and narrates a journey to understand the future of forests trying to stand tall against the forces of climate changeand explores how we, a powerful hand holding a tiny seed, can help.

Harley Rustad, author of Big Lonely Doug

A beautifully written and deeply reported look at the world of trees at this moment of crisis. One of the best and most engaging pictures Ive seen of how climate change has impacted and will impact the story of the species facing it.

James Pogue, author of Chosen Country

THE

JOURNEYS

OF

TREES

A STORY ABOUT FORESTS, PEOPLE,

AND THE FUTURE

Zach St. George

Copyright 2020 by Zach St. George

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Jacket design: Yang Kim

Jacket photograph: Xuanyu Han / Getty Images

Book design by Chris Welch

Production manager: Lauren Abbate

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: St George, Zach, author.

Title: The journeys of trees : a story about forests, people, and the future / Zach St. George.

Description: First edition. | New York, NY : W. W. Norton & Company, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020005951 | ISBN 9781324001607 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781324001614 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Forest conservationUnited States.

Classification: LCC SD412 .S74 2020 | DDC 333.75/160973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020005951

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

To Janet and Judith, David and George

CONTENTS

THE

JOURNEYS

OF

TREES

INTRODUCTION

I n February 2004, Connie Barlow lay down under a small evergreen tree, stared up through its branches, and made it a promise. Im going to find a way, she told the tree. Im going to move you.

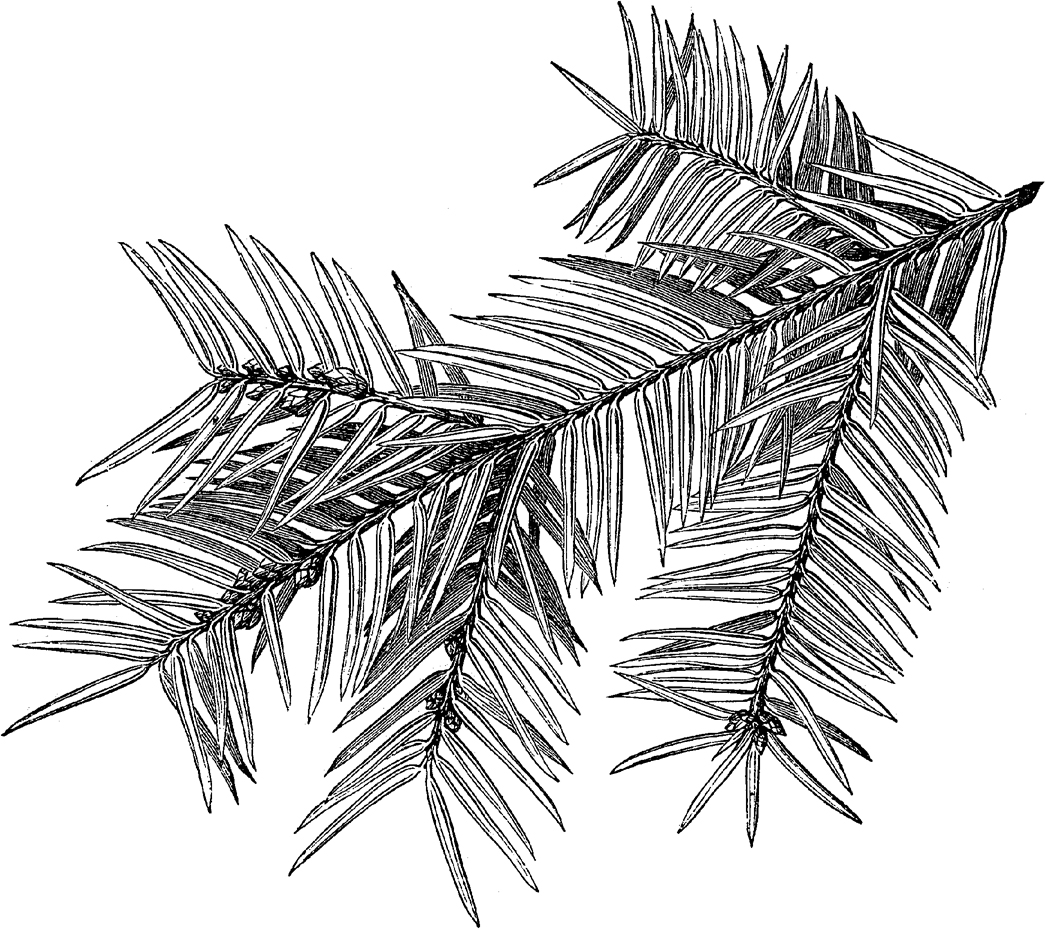

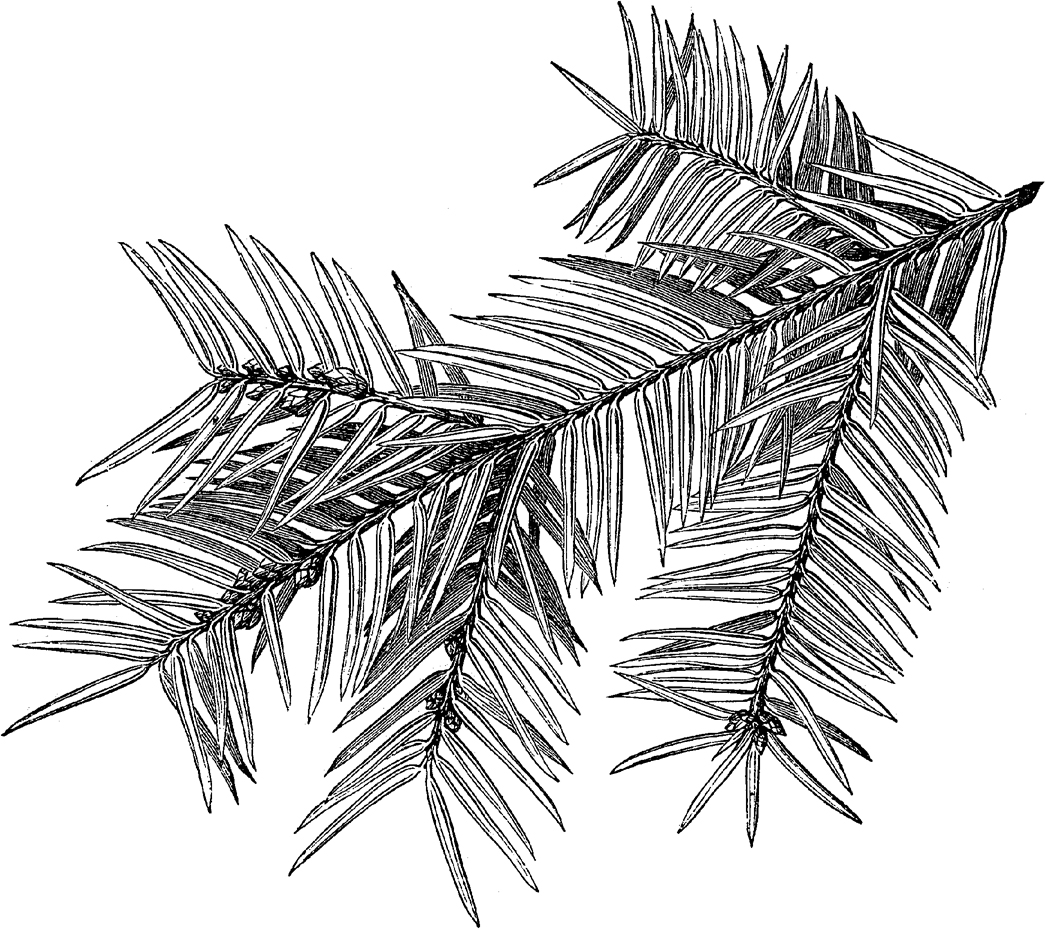

Barlow, a retired science writer and working evolutionary evangelist, was in a state park overlooking the Apalachicola River, which cuts north to south across the Florida Panhandle. The tree was a Torreya taxifolia, called variously in English Florida nutmeg, savine, gopherwood, and stinking cedar, the last for the offensive smell its foliage emits when crushed. Barlow, a partisan, thinks the nickname is whats offensive. She prefers to call the tree, simply, Florida torreya.

The tree is a conifer, with pin-sharp needles and fleshy fruit. From afar, the tree has the draped, disheveled form of an old shag rug and is of medium build, sometimes fifty or sixty feet tall, although its hard to find one that tall today. It is rare, growing over only a couple dozen square miles, in the steep ravines that cut through the limestone bluffs overlooking the Apalachicola River.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Florida torreya was confined to its few square miles, but within these miles it was common. Locals used torreyas for fenceposts and firewood and Christmas trees. But in the 1950s, the torreyas started dying. The culprit seemed to be a fungus. The trees died back to their roots, which then sent up suckers. These suckers would get to be ten or twelve feet tall and a couple inches thick and then they would succumb to the fungus, too. What was the fungus? Why now? Nobody knew.

Decades went by, and the tree grew rarer and rarer. Various people and universities and botanical gardens and state and federal agencies tried to save it, but none of them could wrest it from its terminal slide. Then, in the early 2000s, Connie Barlow visited Torreya State Park, found the suckers, and saw that the problem was a simple oneso simple, in fact, that it beggared belief that nobody had realized it and acted on it before. The problem wasnt the fungus at all. The trees real problem was that it had gotten stuck.

Individual trees, as will be apparent to most people who have encountered one, dont often move around. Once a tree is rooted in one spot, its rare for it to wind up in another. Forests, though, are restless things. Anytime a tree dies or sprouts, the forest it is a part of has shifted a little. The migration of a forest is just many trees sprouting in the same direction. Through the fossils that ancient forests left behind, scientists can track their movements over the eons. They shuffle back and forth across continents, sometimes following the same route more than once, like migrating birds or whales.

This Florida torreya, Barlow thought, was not supposed to be a Florida torreya at all. It should have been a northern Georgia torreya, or a Virginia torreya, or maybe even a Pennsylvania torreya. It should have migrated north at the end of the Pleistocene, 11,700 years ago, but for some reason, it had not. Now it was marooned in hot, sticky Florida, a place growing only hotter and stickier. The fungus was just a symptom of this mismatch, the way polar bears in zoos will sometimes grow algae on their fur and turn green. The Florida torreya, she thought, was a tree in the wrong place. The solution to this problem was simple: Move the tree north.

I n his 1908 book Worlds in the Making, Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius wrote that the enormous combustion of coal by our industrial establishments suffices to increase the percentage of carbon dioxide in the air to a perceptible degree. He predicted this would cause the planet to warm. He saw it as a welcome side effect. We may hope to enjoy ages with more equable and better climates, he wrote, ages when the earth will bring forth much more abundant crops than at present, for the benefit of rapidly propagating mankind. By the 1980s, scientists thought Arrhenius was correct: Human pollution was warming the world. But it seemed likely to be less pleasant than the Swede had imagined. In a 1981 paper, a group of NASA scientists led by atmospheric physicist James Hansen predicted rising seas, growing deserts, and large-scale human dislocations.

The rest of the worlds living things would be rearranged, too. Every species has certain climatic requirementswhat degree of heat or cold it can tolerate, for example. When the climate changes, the places that satisfy those requirements change, too. Species are forced to follow. All creatures are capable of some degree of movementor dispersal, as scientists call it. A mobile creature, like a fish or a bird, might move around throughout its life. But even creatures that appear immobile, like trees and barnacles, are capable of dispersal at some stage of their lifeas a seed, in the case of the tree, or as a larva, in the case of the barnacle. A creature must get from the place it is bornoften occupied by its parentto a place where it can survive, grow, and reproduce. Movement is constant and essential.