To my two forest bathers and nature protectors, Matthew and Axel

Text copyright 2019 by Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review .

Twenty-First Century Books

A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

241 First Avenue North

Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA

For reading levels and more information, look up this title at www.lernerbooks.com .

Main body text set in Adobe Garamond Pro 11/15.

Typeface provided by Adobe Systems.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Koch, Melissa, author.

Title: Forest tal k : how trees communicate / Melissa Koch.

Other titles: How trees communicate

Description: Minneapoli s : Twenty-First Century Books, [2019 ] | Audience: Ages 121 8 | Audience: Grades 9 to 12 . | Includes bibliographical references . |

Identifiers: LCCN 2018010569 (print ) | LCCN 2018011368 (ebook ) | ISBN 781541543935 (eb pdf ) | ISBN 781541519770 (l b : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Plant cellular signal transductionJuvenile literature . | Plant ecophysiologyJuvenile literature . | Plant chemical ecologyJuvenile literature . | Forest ecologyJuvenile literature . | Human-plant relationshipsJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC QK725 (ebook ) | LCC QK725 .K63 2019 (print ) | DDC 5 81.7/14dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018010569

Manufactured in the United States of America

1-44313-34559-9/6/2018

Contents

Introduction

Reconnecting with Trees

Chapter 1

Our Trees, Our Life

Chapter 2

Healthy Trees, Healthy Humans

Chapter 3

Trees Talk to One Another

Chapter 4

The Forest Canopys Cry for Help

Chapter 5

Listening to Forests

Conclusion

Next Steps

Introduction

Reconnecting with Trees

The wonder is that we can see these trees and not wonder more.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, nineteenth-century US writer and poet

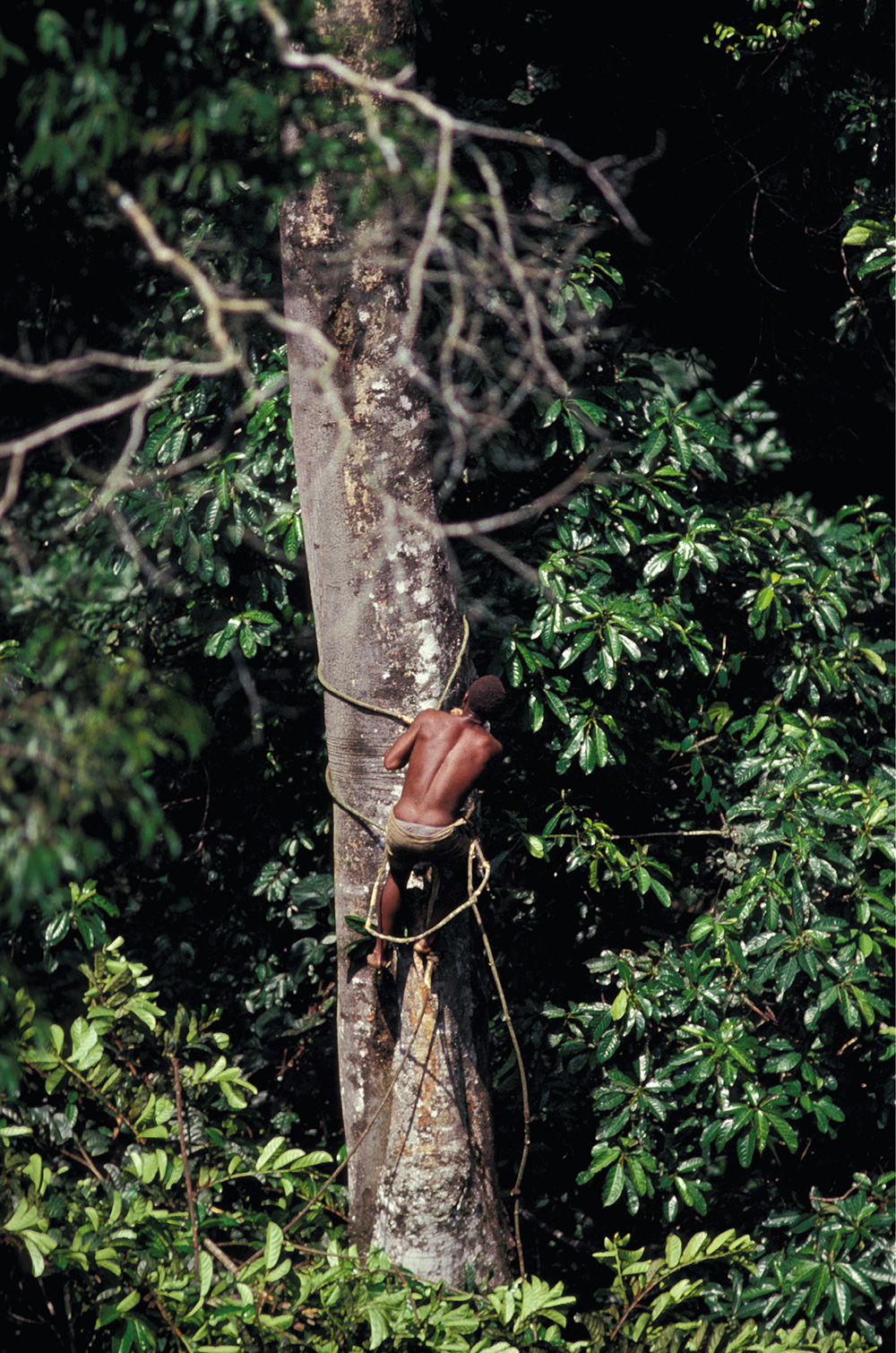

F or thousands of years, the Mbuti Pygmies made their homes in the rain forest of lands that became the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in Africa. The villagers who lived nearby feared the darkness and animals in the forest. They cut back the trees to build homes and to farm. But the Mbuti embraced the forest in every aspect of their lives. For food, they hunted forest animals, such as pigs and monkeys. They also gathered forest plants, mushrooms, nuts, fruits, and their favorite food, honey. They made clothing from the leaves and bark of ficus and fig trees. They used long tree limbs and leaves to construct shelters. The forest was also their pharmacy: they made medicine from the oils, bark, and leaves of trees and other plants.

Sunlight filters through the forest in North Cascades National Park in Washington State. Some of the tall trees there are hundreds of years old.

British anthropologist Colin Turnbull studied the Mbuti Pygmies in the 1950s and wrote about their lives in a book called The Forest People . A Mbuti man named Moke told Turnbull how his people connected and communicated with the forest:

The forest is a father and a mother to us, and like a father and mother, it gives us everything we needfood, clothing, shelter, warmth... and affection. Normally, everything goes well because the forest is good to its children, but when things go wrong, there must be a reason.... So when something big goes wrong, like illness, bad hunting, or death, it must be because the forest is sleeping and not looking after its children. So what do we do? We wake it up. We wake it up by singing to it, and we do this because we want it to awaken happy. Then everything will be well and good again. So when our world is going well then we also sing to the forest because we want it to share our happiness.

The Mbuti still live in the forests of the northeastern DRC; still obtain food, clothing, and shelter from trees; and still revere their forest homes. They are not the only humans who venerate trees. Trees have been central to human society for thousands of years. Many cultures tell of a tree of life from which all other life springs. This concept also appears in twenty-first-century pop culture, including the fantasy/science fiction film Avatar (2009). The tree of souls in Avatar is a giant willowlike tree with a luminescent glow. It connects all living things to one another and to their god, Eywa, on the planet Pandora. The people on Pandora live in large trees. All the planets trees are connected and communicate with one another.

A Mbuti man in the Democratic Republic of the Congo climbs a tree to collect honey. For thousands of years, forest plants and animals have supplied the Mbuti with food, shelter, and clothing.

Life-Giving Trees

Stories of a tree of life or tree of souls are based on the fact that trees are essential for living things. Trees provide shelter, medicine, and food for millions of plant and animal species, including humans. Trees also help cool us. Think about standing under a trees shade on a hot day. Ahhhh .

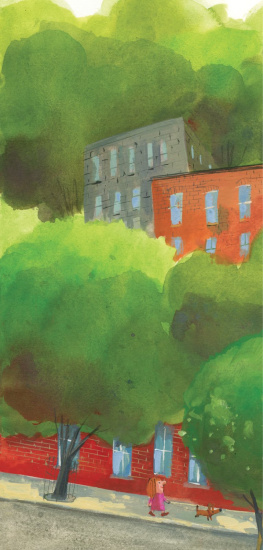

People have long felt the mental and physical benefits of being around trees, regardless of the temperature. Think about how calming it is to walk in a park or forest compared to walking down a busy city street. Health experts have even found that just looking at a picture of trees can help a person relax.

Water is essential to life on Earth, and trees play a big role in Earths water cycle. They take up water through their roots and release it into the atmosphere through their leaves. In the process of making food, trees also release oxygen, a gas that humans and other animals must have to live.

Dying Forests

Forests are vital to life on Earth, but forests are in trouble. Around the world, humans are cutting down trees to make products such as paper and furniture and to obtain foods such as palm oil. Humans are also clearing forests to build farms, homes, industrial plants, roads, and cities. The loss of forest for any reason is called deforestation.

Forest degradation involves harm to or partial destruction of the forest ecosystemthe community of living and nonliving things in a forest, such as plants, animals, soil, and water, that rely on one another for well-being. Many human activities can degrade forests. For example, when humans pollute the air or water, they might endanger the health of living things in a forest. When humans allow livestock to graze in or near forests, the animals often eat tree seedlings, so they never become adult trees. Forest degradation can be temporary or permanent. Unlike deforestation, the forest still exists, but the trees and other living things there are less healthy than normal and more vulnerable to disease.

For thousands of years, our human ancestors obtained food by hunting animals and gathering wild plants. They cut down a few trees to build tools, boats, or shelters, but they didnt clear large areas of forest. About ten thousand years ago, people in the ancient Middle East began farming. At first, farmers cleared only small areas of land to plant crops. They didnt cut down entire forests. But eventually, human society grew more complex. People cut down large areas of forest to build homes, cities, and large farms. When European settlers migrated to North America in the early seventeenth century, vast forests stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Plains, with other large forests out west. In lands that would become the United States, forests covered about 1,023 million acres (414 million ha), nearly half the size of the present-day nation. Since the first Europeans arrived, Americans have cut down about 256 million acres (104 million ha) of forest to build farms and cities.