Fallen redwood, Humboldt Redwoods State Park, California

Introduction

WHEN MY PUBLISHER asked me if I wanted to write a book for people to take with them when they went out walking in the forest, I said yes right away. My love for wooded areas has informed most of my choices in life, which is interesting, because I fell into this line of work quite by chance. I originally planned to study biology because, like many high school graduates today, I didnt know how best to channel my love of the natural world. Then my mother came across a small advertisement in the local newspaper from the state forestry commission: they were looking for trainees. I applied, was accepted, and spent the next four years studying the theory and practice of forestry.

As it turned out, the job for which I studied so hard did not come close to fulfilling the dreams I had nurtured for so long. The first problem, which turned out to be the tip of a whole iceberg of problems, was working with heavy machinery, which destroys the forest floor. This was followed by using insecticides that kill on contact, clearcutting, and cutting down the oldest trees (the ancient beeches I love so much). I found these tasks increasingly worrisome. Over the course of my studies, I had been taught that these practices were necessary to ensure the health of the forest. It might amaze you to learn that there are still thousands of students who believe their professors when they pass down these same lessons. My discomfort soon turned to horror, and I didnt know how I was going to survive a career in forestry.

In 1991, I was lucky enough to find a community that shared my values. Located in the Eifel mountains in Germany, the community of Hmmel owned forestlands and wanted to manage them sustainably. Together we created a plan that included a mix of uses, including parcels to be left untouched and parcels where resources would be extracted carefully to minimize impacts. The guiding principle behind our plan was to involve the community in the decision-making process. I designed several activities to help us achieve our goals. Survival-training weekends and building log cabins were the most adventurous. Mostly, I led guided tours through the wonderful world of trees.

After the tours, people often asked me where they could read up on what they had just learned. I could only shrug, as I did not know of any books on the subject. My wife kept pressuring me to put something in writing for visitors to take home with them. And so, while on vacation in Lapland, I committed to paper what I would talk about on a typical guided tour. I sent the text off to several publishers and told my wife: If no one agrees to publish my book by the end of the year, writing is clearly not for me.

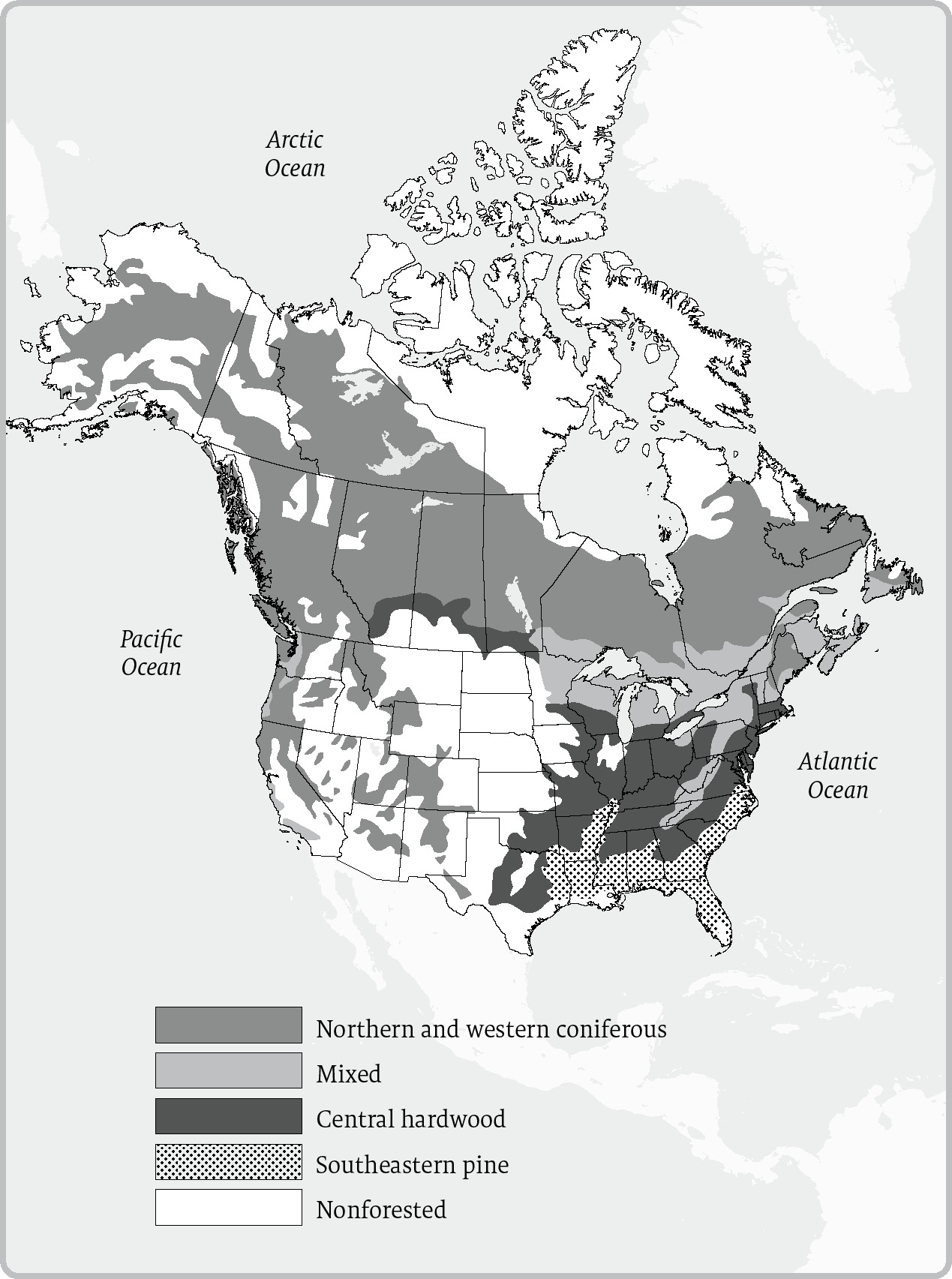

As you can tell from the book you now hold, that is not what happened. Since the publication of my first book, The Hidden Life of Trees, I have found great joy in expanding what I do. Now I can get many more people excited about forests because, in my opinion, forests are not being used nearly as much as they should be. Im not talking about the depredations of the timber industry, which does altogether too much in too many places. Im talking about the adventures, great and small, waiting to be discovered amongst the trees. And to find them, theres just one thing you need to do: take a walk in a forest. I am so happy that Jane Billinghurst, my longtime English translator, has come along on this journey to help point out the amazing variety of adventures to be found in forests in North America.

BEFORE WE SET OUT, it might be helpful for you to know what I mean by the word forest. The trees most of us know best are lined up in rows along city streets, set out in tasteful arrangements in urban parks, or displayed as exotic specimens in arboretums.

Im sure youve all seen sidewalks buckling as tree roots push up from underground. Or noticed the cages around trunks to protect them from passersby. Or heard about trees whose roots have penetrated water pipes, leading to the miscreants swift removal. Trees in urban areas that are not removed for bad behavior are usually cut back to keep them neat, tidy, and safe for pedestrians walking beneath them.

Life for trees in parks and in arboretums is a little better, but not much. There are often just one or two of the same species and they may well be growing far from home, struggling in conditions that are new to them. They do not have an extended family to support them, and they grow old without ever having the opportunity to watch a new generation grow up around them.

When I talk about a forest, Im not talking about rows of trees in urban settings or individuals in parks. Im talking about a large group of trees growing together. But are all large stands of trees away from cities necessarily forests? I trained as a forester. My job was to go out into what I thought of as a forest to look at individual trees and evaluate them for their economic potential. What was important was how straight they grew and how free they were from pests and diseases.