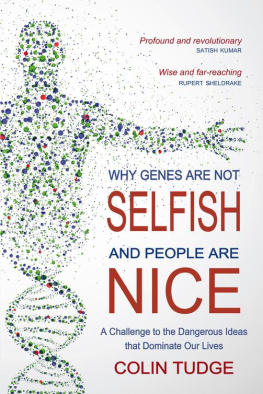

This wise and far-reaching book points the way to a better, more inclusive kind of science and a better, more inclusive kind of religion in a positive, constructive relationship. This is surely what we need most in the twenty-first century and Tudge is a genial guide for all who feel the need to move on from scientific and religious fundamentalism, environmentally destructive capitalism and an economic philosophy of selfishness, competition and limitless growth. Tudge points the way to a new kind of agriculture, a new way of living in harmony with our planet and the universe, and with each other. This book is an impressive synthesis and is admirably non-technical, conversational and approachable. Tudge, one of our most distinguished science writers, is a prophet for our time, and a very welcome voice of sanity and reason.

R UPERT S HELDRAKE

Colin Tudge is a scientist with a difference; a scientist who is not afraid of embracing transcendence. He sees no conflict between science and wisdom. This profound and revolutionary book is a deep exploration of science, life and transcendence. It is a courageous critique of materialism and a persuasive argument in favour of fresh thinking. Tudge challenges us to come out of our narrow view of science and look at life with a much bigger perspective.

S ATISH K UMAR

This book more than lives up to its subtitle. It does indeed challenge big bad ideas, whether they be about the natural world, the human condition within it, or our habits of thought and behaviour, and suggests some bigger, better ideas for the future. In short replace the conventional wisdom. All this is laid out in easy but scholarly fashion, and the conclusions are a personal testament. Think differently is the message. We are now better able to do so.

S IR C RISPIN T ICKELL

Contents

I have been writing this book in my head for more than sixty years. That is, I realised at the age of six that I wanted to be a biologist (although I dont think I used words like biologist at that time) for I was, as I think most budding biologists are, besotted by nature; by the feeling that life is endlessly absorbing but also that it is magical. It has the quality that the Lutheran theologian Rudolf Otto called numinous although I didnt learn that word either, until very much later. I was lucky enough to be born at a time when excellent education was free, and went on to a school where science was excellently taught, and from there to read zoology at a very old and cold university that had somehow managed to keep its spires above the encircling swamp, and there too the teaching was outstanding. But that was in the 1960s and we tended to pursue the ludicrous idea that all life could be reduced to physics, and physics to maths, and that was the end of it.

Yet I never quite felt that that was the end of it. I always had an ill-formed but nonetheless powerful feeling that there is a great deal more to life and the universe than meets the eye or ever can meet the eye, no matter how much science we may do. I never quite managed to become a Christian but I always felt (despite my youthful denials) that religion was saying important things, although I wasnt quite sure what. I always felt too in fact I think I took it to be self-evident that St Francis was right: that other creatures are truly our fellows; and this feeling was constantly reinforced by my lifelong absorption in the idea of evolution. I also felt that the Founding Fathers of the US were stating the obvious in the second paragraph of their Declaration of Independence when they said that all men are created equal. Of course they are. How could it be otherwise?

Then at about age seventeen I started reading Aldous Huxley, and in particular his magnificent saga Point Counterpoint; and so had my first intimation that all knowledge is all one or at least that it could and should be one. The fragmentation into science, philosophy, and religion was just for convenience, and it was a sad and dangerous thing to leave them in their separate packages (or indeed on separate campuses). Later I learned that everything could and should be brought together under the grand heading of metaphysics; and that the unified vision that metaphysics can provide was needed to underpin the practicalities of politics and economics, and hence of our day-to-day lives. Metaphysics brings coherence (and nothing else does).

All these ideas kicked around in my head for about half a century until finally, about three years ago, I decided it was time to pull things together before the grim reaper came a-knocking. So heres the result. It isnt a finished, definitive work because in an endeavour like this there can be no such thing. It is, however (I hope) an agenda for discussion. The very concept of metaphysics has gone missing, and as the Islamic scholar Seyyed Hossein Nasr has commented, the loss of metaphysics from the western world might be seen as the root cause of all our ills. That loss, after all, means the end of unified thinking. My ambition, then (besides the wish to consolidate the ponderings of a lifetime) is to put metaphysics back where it belongs, at the heart of all human thinking and all human affairs.

I am aware of my debt to an enormous number of people far too many to list, for much of what all of us learn is by osmosis, entirely informally, often through chance remarks. I must though mention my teachers at school and university, for teachers really do set the tone. Then in my early journalistic days I had particularly illuminating conversations with Peter Bunyard, Bernard Dixon, Geoff Watts, and Fred Kavalier. I am very grateful too to Helena Cronin, who in the 1990s invited me to join the Darwin Centre at the London School of Economics as a Visiting Research Fellow, where I met some of the worlds finest biological thinkers. I also had good conversations with Sophie Botros who introduced me to some key notions of philosophy. More recently, since we moved to Oxford, my wife Ruth and I have spent many a pleasant and instructive evening with Paul and Chris Wordsworth, and John and Sally Lennox, who combine medicine and maths with devout Christianity. I have also enjoyed good discussions with my old friend Georgina Ferry, on science in Elizabethan times. Over the years, too, I have learned a great deal from Rupert Sheldrake and Robert Temple; and from Tim Bartell, who put me right (I hope) on the structure of moral philosophy. At Oxford I have benefited enormously from the Ian Ramsey lectures on science and religion, and especially from (albeit brief) conversations with John Hedley Brooke. Through Aaron and Sid Cass I have got to know many of the people at the Beshara School at Chisholme on the Scottish borders, where metaphysics is discussed with particular emphasis on the teaching of Ibn Arabi. I have also been lucky enough over the past few years to form an association with Schumacher College at Dartington in Devon, and in particular with Satish Kumar.

Finally I am very grateful to Sir Crispin Tickell, Rupert Sheldrake, and my nephew John Harris who read an earlier draft of this book and gave me valuable advice; and to Christopher Moore at Floris Books who has done much to help me tidy it up. Most of all however I am grateful to my wife, Ruth (West), who looks after me remarkably well and is also in some relevant areas a far better scholar than I am, and a very astute critic.

Colin Tudge, November 2012

I want to present a different view of life compounded of ideas that in most important respects are completely opposed to the kinds of beliefs that now dominate the modern western world and so have come to dominate the world as a whole. For we in the western world have misconstrued well, just about everything: the nature of the universe, of life, and of our own human selves; the nature of truth; and the nature of right and wrong. From these fundamentals the errors compound: we treat the world badly, we treat each other badly, we put tremendous store by ideas that are decidedly flimsy and afford the people who promote those ideas far too much respect. To be more specific, our politics is unjust, our economic system borders on the insane, our governments for the most part are not on our side, our science which should be our great liberator has become the handmaiden of big business, while religion is all over the place, fractious and narrow-minded where it should be all-embracing.