Hundreds, even thousands, who started the trip did not live to finish it. Those who made it all the way to Californy found a harsh reality, which failed to match their dreams.

In 1848, gold was discovered in California! This exciting news spread eastward. People from all walks of life with dreams of enormous riches packed up their belongings and left their comfortable homes behind in search of the hidden treasure. They entered into and helped create the rough, fast-paced, and sometimes glamorous world of the California gold rush. Some struck it rich; many more did notbut they all had a story to tell.

In The California Gold Rush: Stories in American History, author Linda Jacobs Altman describes the development of this rugged world of the mining towns, which sparked the development of California. Altman also highlights the stories of prospectors, bandits, and thrill seekers who make up the legend and the myth of the time.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Linda Jacobs Altman specializes in writing about history, social issues, and multicultural subjects for young people. Her recent titles include Shattered Youth in Nazi Germany: Primary Sources From the Holocaust and EscapeTeens on the Run: Primary Sources From the Holocaust.

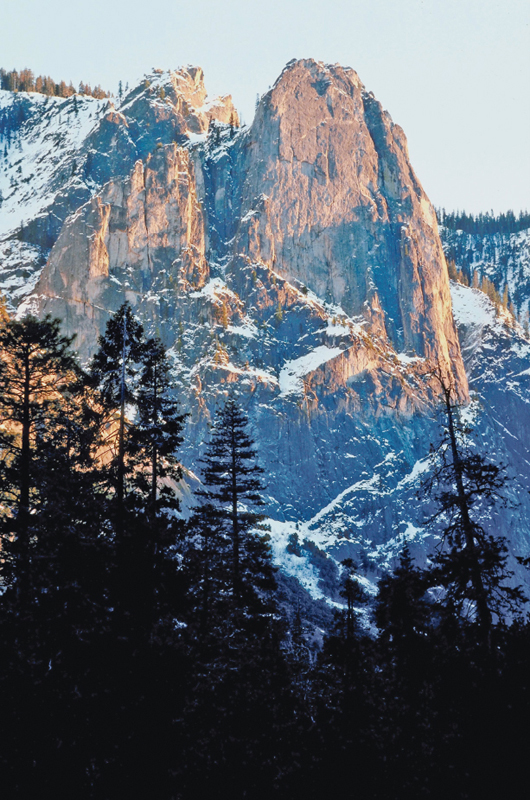

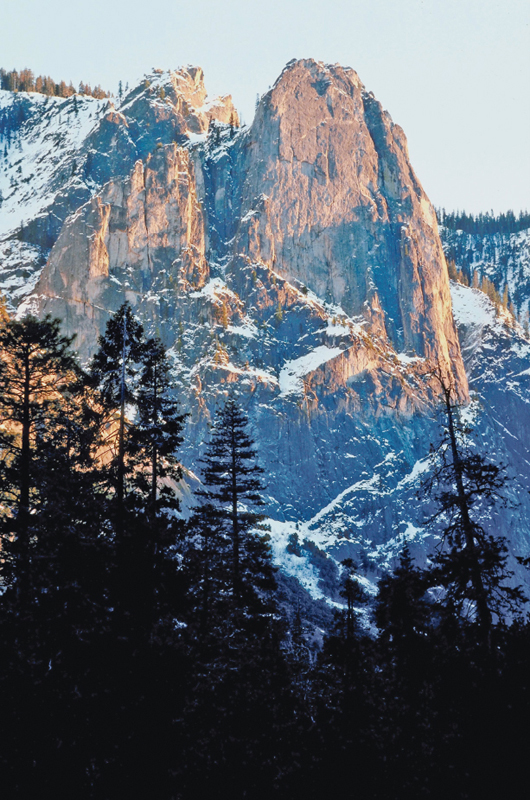

Image Credit: 2010 Photos.com, a division of Getty Images

The Sierra Nevada Mountains.

Gold! In 1848, that magic word started a whole nation dreaming. Gold was discovered in Californiaenough for everybody, with plenty left to spare. The news spread across the country, triggering one of the most amazing migrations in history.

People came by sea in anything they could get to float, from sleek clipper ships to converted whalers. They came by wagon, over the prairies and through the mountains. One enterprising fellow piled all his worldly possessions in a wheelbarrow and walked, whistling Yankee Doodle as he went. He whistled and walked and pushed his way to Salt Lake City, Utah, where he finally joined a wagon train rather than cross the Sierra Mountains alone.

Hundreds, even thousands, who started the trip did not live to finish it. Those who made it all the way to Californy found a harsh reality, which failed to match their dreams. The mining towns were rude and crude, and the work was backbreaking.

People from many places and many walks of life came together in a common enterprise. All too often, they met as competitors rather than friends. Lawlessness and trickery ran rampant, and nonwhites were especially vulnerable to attack. In the mid-1800s, most white Americans considered themselves superior to African Americans, Asians, Latinos, Native Americans, and anybody else whose appearance and culture differed markedly from their own. Racist language that would shock us today was part of the normal vocabulary. In this atmosphere, minorities struggled to just survive, let alone prosper.

Everything seemed fast in gold country. The population boomed. Businesses came and went. Miners made a fortune one day and lost it the next. Whole towns grew up overnight and disappeared just as quickly. People lived hard, played hard, and, too often, died hard.

California made a magnificent stage for this drama. With deserts and mountains along its eastern border and an ocean to the west, it possessed a larger-than-life, mythic quality that went beyond the lure of gold. Even its name was the stuff of legend. Thinking they had found the island domain of Calafa, beautiful, black-skinned queen of the Amazons, the Spanish conquistadors named their discovery in her honor.

The story of the hardy dreamers of 1849 is shot through with outrageous legends, epic adventures, and facts that seem a good deal stranger than fiction. Perhaps that is why it remains as fascinating today as it was when a generation of Americans set off to conquer those golden hills.

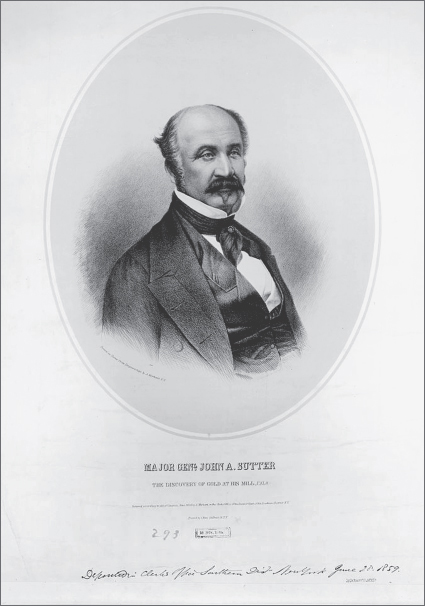

When California belonged to Mexico, it was elegant, aristocratic, and unfailingly hospitablea land of adobe ranch houses and flamenco guitars, of ladies in lace headdresses, and of gentlemen who never sullied their hands with manual labor or worried much about anything so vulgar as money. This was the California that attracted John Sutter. He dreamed of power, prestige, and enough land to build an empire. He could not possibly guess that finding gold would one day destroy that dream.

Johann August Sutter was born on February 15, 1803, in the German village of Kandern. His parents were Swiss working folk who lived in comfortable obscurity. Jakob Sutter worked as foreman of the Kandern papermill, a position his father had held before him. The family expected Johann to follow in the old traditions, but the imaginative young man had other ideas. He hopped from place to place and job to job, looking for work that would suit him. He found a wife instead. On October 24, 1826, he married Anna Dubeld of Burgdorf; the next day she gave birth to their first son. This instant family had a significant impact on Sutter. For a time, he made an honest effort to settle down and tend to his responsibilities.

To help him along, Sutters new mother-in-law set him up in the drygoods business. He brought tremendous energy to the project, along with a willingness to work and a buoyant faith in his own abilities. Unfortunately, he also brought an appalling lack of business savvy. He wanted to go too far, too fast, and his impatience cost him dearly.

After four years of mismanagement, the business teetered on the edge of bankruptcy, and Sutter faced financial disaster. In the 1830s, debtors prison was the fate of a man who could not pay his bills. Sutter got out of the country one step ahead of the police, leaving his wife and children to fend for themselves. In the summer of 1834, he landed in New York, with the past securely behind him and a new continent ahead.

Sutter was the sort of charming rascal who could sell sand in the desert, and although he was not an out-and-out thief, he was not overly concerned about the ethics of his schemes. The newness of America appealed to him; here, he could escape his working-class origins and become the person he longed to be.

He Americanized his name from Johann to John and set about building a new and distinguished identity for himself. He wove that identity from the bits and pieces of his life: a few stray facts and half-truths, generously seasoned with daydreams and fantasies. So it was that the indifferently educated son of a Swiss papermill foreman became Captain John A. Sutter, highborn veteran of the Royal Swiss Guards, in service to King Charles X of France.

SOURCE DOCUMENT

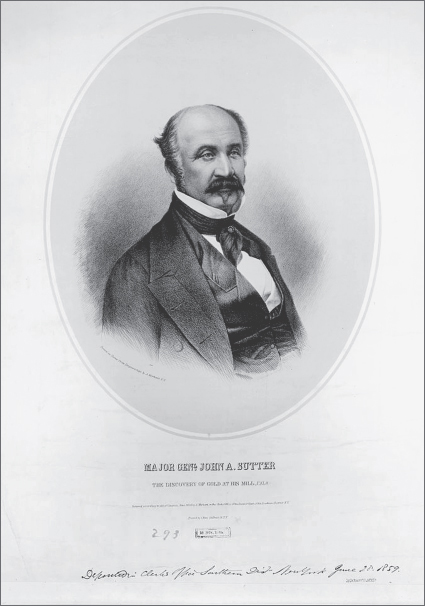

Image Credit: Library of Congress

John Sutter was not interested in gold. Instead he dreamed of becoming a land baron, with vast holdings and a respected name.

Sutter spent freely to surround himself with an aura of wealth and privilege. He dressed well, entertained lavishly, and became so expert at playing the aristocratic adventurer that he probably believed his own charade. During his first five years in America, Sutter crossed the continent, visited Russian holdings in the Northwest, and sailed to Hawaii. Along the way, he ingratiated himself with several wealthy Americans, one Russian admiral, and a kingKamehameha III of Hawaii.

A thoroughly convincing Captain John A. Sutter arrived in California with borrowed money, a contingent of Hawaiian workers he had hired and brought from the islands, and a sheaf of glowing letters describing him as a man of substance, character, and leadership ability. Sutter made his first landfall in California at Yerba Buena (good herb), on the northern coast. It was a scruffy, scrawny place with nothing special about it except a natural harbor. Richard Henry Dana painted a bleak portrait of it in