For Virginia I. Giddingsmy mother, my friend, my support

Only the BLACK WOMAN can say when and where I enter, in the quiet, undisputed dignity of my womanhood, without violence and without suing or special patronage, then and there the wholerace enters with me.

Contents

Inventing Themselves

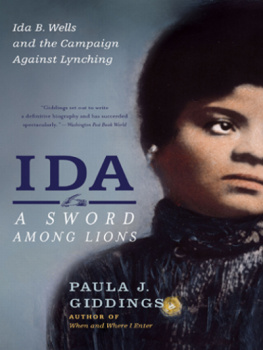

To Sell My Life as Dearly as Possible: Ida B. Wells and the First Antilynching Campaign

Casting of the Die: Morality, Slavery, and Resistance

To Choose Again, Freely

Prelude to a Movement

Defending Our Name

To Be a Woman, Sublime: The Ideas of the National Black Womens Club Movement (to 1917)

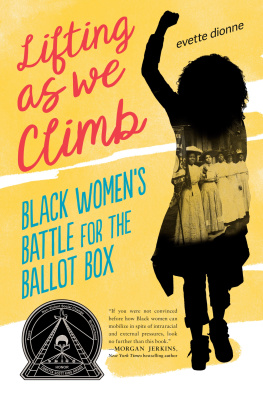

The Quest for Woman Suffrage (Before World War I)

A World War and After: The New Negro Woman

Cusp of a New Era

The Radical Interracialists

A New Era: Toward Interracial Cooperation

A Search for Self

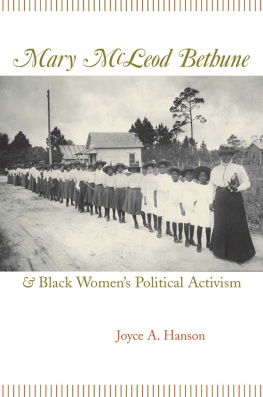

Enter Mary McLeod Bethune

Black Braintruster: Mary McLeod Bethune and the Roosevelt Administration

A Second World War and After

The Unfinished Revolution

Dress Rehearsal for the Sixties

SNCC: Coming Full Circle

The Womens Movement and Black Discontent

Strong Women and Strutting Men: The Moynihan Report

A Failure of Consensus

Outlook

The occasion of a new edition of When and Where I Enter, first published in 1984, has made me think about the uses of history in different periods: how we plumb the past for inspiration; for evidence of things seen but unacknowledged. During segregation we celebrated our contributions to civilization, or, in other words, our ability to land on our feet after being thrown from great heights. In the sixties and seventies, we embraced our resistance and agency; and in the eighties, we uncovered our canonical presence in the full scheme of American history and culturehigh and low.

An indomitable belief in the continuing progress of each succeeding generation was, like a brightly colored thread, woven throughout the record of our experience. This, of course, is a very American notion. But for black womenmany of whom, like myself, are inscribed with the image of a great-great-grandmother who, though born a slave, was able, when the time came, to turn a raised head toward freedom; or of a grandmother who trekked north and, with savings from domestic work, sent my mother to collegethis belief was an extraordinary article of faith. Surely it was at the heart of the economic, social, and political convictions that drove the womens and black rights movements of the sixties and seventies.

In an important way that faith was borne out in the eighties and nineties for African Americans in general and women in particular. In that period, the voice of black women, the living narrative of our experience, not only emerged but began to define the literature, arts, and scholarship that were informed by it. In another measure of progress, access was gained to newly desegregated institutions and occupations to the extent that though still earning less than all men (including black men), we have reached parity and in some instances surpass the earnings of white women. These gains in turn contributed to the significant increase in the median income of dual-income black families, from $26,686 in 1983 to $39,601 in 1990. There have been other gains, black women as elected officials, for example, including the first black woman elected a U.S. senator.

But a new cycle has eclipsed the old, and these gains are no longer seenor feltin the context of the social movement optimism of the last three decades. One reason is increasing black povertyespecially of female-headed households; another is the onset of an antilabor economy; a third, and most defining, is an at-first predictable conservative reaction that turned into a crimson backlash of considerable ferocity. In its midst, although reactionaries were unable to undermine the social movement ideals of equality and opportunity for all, they nonetheless managed to reinterpret the meaning and the valence of those principles as they applied to people of color, to the poor, and to women. In this way, they twisted welfare safety nets into nooses; made the level playing field of affirmative action into reverse discrimination, recast poverty as a function of morality rather than economic policy. And as for feminism, they charged that it didnt save womens lives, but ruined themand family and daddy, too.

If the countertide had come from just one direction, it would not have been so brutal, but it also included conservative elements of the black community as wellparticularly regarding the achievements of women. This is at variance with the abiding faith of our progress, our legacy as agents of change, even our survival.

When I think about how torn and ambivalent black women become in the face of such developments, it leads me to think that in this new era, we must search history for a new element, something that in a way is less familiar to usourselves. For, I think, even when we possess a breathtaking sense of agency, when we have heroically resisted, when we have proven our worth and the wealth of our presence, we have seen ourselves primarily in the context of othersof men, of community, of family, of employers. This has made us indispensablethose who dont know our history, dont know their own, Toni Morrison saysbut that idea has also pulled us back against our own interests when our winds should be pushing us in another direction. So we become indispensable to everyone but ourselves.

In the nineties and beyond, we might ask then, who are we as ourselves? What would we say to Anita Hill outside the earshot of whites or men or our mothers and fathers? What do we feel about a Million Man March, not withstanding the participation of our sons and brothers and husbands? Who are we when no one yearns for us, or when we are in full possession of our sexuality? Who are we when we are not someones mother, or daughter, or sister, or aunt, or church elder, or first black woman to be this or that?

In the next century, we should search our history for the answers to these questions, which I believe will evoke the extraordinary will, spirit, and transformative vision that can reconnect us to loved ones, communities, and reform movements in revolutionary ways. For what I have learned in the eighties and nineties is that the faith in progress our forebears taught was not only in terms of our status in society, but in our ability to gain increasing control of our own lives.

P AULA G IDDINGS

she had nothing to fall back on; not maleness, not whiteness, not ladyhood, not anything. And out of the profound desolation of her reality she may well have invented herself.