I n 1984, soon after I had published When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America , I received a call from Hortense G. Canady, the national president of Delta Sigma Theta. She congratulated me on the bookand then offered me two propositions. The first was to invite me to Deltas seven regional conferences where I would have the opportunity to talk about the book, and offer it for sale to those who attended the meetings. It was a gesture of support, something that Black sororities are well known for. And Delta, especially, has had a long tradition of supporting women in the arts. The second proposition was for me to write a history of the organization in time for its seventy-fifth anniversary in 1988. I had to weigh that proposal more carefully, both as a writer interested in Black womens history, and as a Delta who had some knowledge of the obstacles I would encounter.

Writing the history would give me an opportunity to explore the inner workings and dynamics of a major Black womens organizationsomething that I could not do in When and Where I Enter. Such organizations are an important, yet much neglected, subject in both Black and womens studies. As one of the largest Black womens groups in the world, with some 125,000 members, Delta was certainly a major one. The fact that its membership also included significant historic and contemporary figures such as Mary Church Terrell, Sadie T. M. Alexander, Patricia Roberts Harris, Barbara Jordan, Leontyne Price, and many other women who were leaders and pioneers in their fields, made it more so.

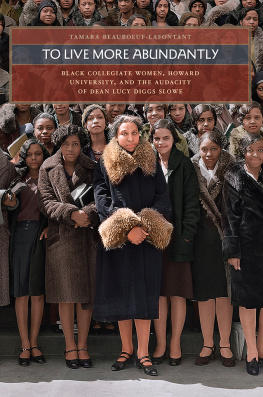

As a college-based group, its history also would shed light on the experience of Black women in higher educationa driving force in our history. Barred from most occupations, Black women had few choices besides domestic work or the womens professions, such as teaching or social work. Education, then, was the dividing line between a life of drudgery and crude exploitation, and the greater quality of life and status derived from professional work.

That such aspirations were not sanctioned by society defined the nature of Black womens organizations. Most are what sociologists call social movement organizations whose purpose is to change individuals within them and/or the society. Like other Greek-letter groups, Delta Sigma Theta was founded by young college women with the idea of creating social bonds or a sense of sisterhood among its members. Its primary focus, then, has been on transforming the individual. At the same time, however, its founding in 1913, a time of both racial and feminist ferment, also imbued it with a secondary purpose: to have an impact on the political issues of the day, notably the woman suffrage movement. By 1925, the organization made its first public pronouncement against racism and four years later created a Vigilance Committee whose purpose was to enlighten the growing membership about political and legislative issues and thus prepare them to become agents of change. This aspect of Delta distinguished its beginnings from the other sororities, both Black and White, that preceded it. It also makes contemporary Black sororities, in general, different from most of their White counterparts.

The history of Delta is better understood when seen in the light of the principles that govern social movement organizations. For example, they must be able to adapt to changing environments: in this case, the ever changing exigencies of race relations and the attitudes toward women. Consequently, Delta has had to alter its purposes and goals throughout the yearsand must continue to do soas well as its internal structure to accommodate them. This makes the Black sorority a particularly dynamic organization.

At the same time, however, changes cannot occur too abruptly or without the consensus of an increasingly diverse constituency. For like other social movement organizations, its viability is dependent on the growth of its membership, which in turn, is largely determined by the number of its members who feel that the sororitys goals are in harmony with their own.concentrated, it invites apathythe kiss of death for a social movement organization.

Social movement organizations are also dependent on the attitudes of the larger society toward both the movement that they represent and the organization itself. This, too, has important implications in terms of its public activities and the need to maintain not only respect but a deep loyalty of its members.

The sorority, I knew, would also be an interesting subject to study because it is an exclusive or closed membership organization. Undergraduate members must be in college. All members must be invited to join, and undergo a final selection process that includes both quantifiable criteria, for example, grade point average, and/or subjective assessments regarding achievement and character. Against the long experience of discrimination and exclusion in the broader society, and color and class distinctions within the race itself, debates regarding the various criteria for membership have, historically, been particularly emotional and intense. Behind the internal debates, of course, is how the organization sees its mission and itselfa vision that has constantly reshaped itself during different periods of Deltas history.

Despite the inherently controversial nature of an exclusive Black organization, it also has certain advantages. For one thing, a closed membership group is better able to take on new goals. For another, it is less subject to membership declines and conflicts in the face of competing social movements. This is even more true for an organization with solidarity incentives, one that emphasizes coherence, or, in this case, sisterhood, within its membership. And because the focus of its leaders is mobilizing its membership for tasksrather than attracting members through a charismatic leadership stylethere is greater diversity in the kind of women who lead the organization, and more emphasis on getting those tasks done.

While there was no question that the sorority had historic importance, I also knew that there would be difficulties in writing the history. Systematic efforts to organize its archives were still in the early stages, and documentation is scattered and incomplete. And I was afraid that many of those who had a long-standing and thorough knowledge of the sorority would be reluctant to reveal its inner workings and problems. I was not willing to write a public relations tract, and I wondered about how much freedom I would have to get beneath the skin of the sorority and write about its weaknesses as well as its strengths. Concerning the latter, President Canady assured me that she would welcome constructive criticism, and that it was important to give a realistic picture of the organizationand she noted as much to the membership. Her style of leadership convinced me that the organization would be supportive, and that I would have a free reignwhich turned out to be true.