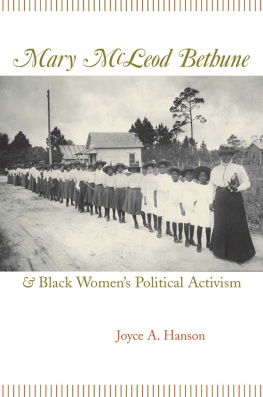

Mary McLeod Bethune & Black Womens Political Activism

Copyright 2003 by

The Curators of the University of Missouri

University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65211

Printed and bound in the United States of America

All rights reserved

First paperback printing, 2018

Library of Congress-in-Publication Data

Hanson, Joyce Ann.

Mary McLeod Bethune and Black womens political activism / Joyce A. Hanson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8262-2154-4

1. Bethune, Mary McLeod, 18751955. 2. African American women political activistsBiography. 3. African American women educatorsBiographyJuvenile literature. 4. African American women social reformersBiographyJuvenile literature. 5. African American womenPolitical activityHistory20th century. 6. African AmericansPolitics and government20th century. 7. African AmericansCivil rightsHistory20th century. I. Title.

E185.97 .B34 H36 2003

370'.92dc21

2002153613

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

Typefaces: Adobe Caslon and Caslon No 540 SwashD italic

ISBN-13: 978-0-8262-6404-6 (electronic)

To all the women who have brought us to this moment.

Acknowledgments

Historical writing is a solitary endeavor. However, doing the research and revising a long-term project is really a group effort. I do owe many people my profound thanks and I am grateful to everyone who encouraged and supported me throughout this project. First, I want to thank Buddy Enck, who reawakened my interest in African American history and encouraged me to pursue a graduate degree. Susan Porter Benson possesses the very best attributes of a graduate adviser. She has been there to reassure me, but more important, she prodded me to think harder and reconceptualize many of my ideas. Donald Spivey has been with me on this project from its inception. He unfailingly promoted my work while subtly persuading me to expand my original range of interest. For that, I am eternally grateful. The dissertation on which this book is based was immeasurably better because of their patience and commitment. I also owe a special thank-you to everyone at the Institute for African-American Studies at the University of Connecticut, especially Rose Lovelace and Ron Taylor, who provided both financial and moral support.

The archivists at the National Archives, Library of Congress, Harvard University, and the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library gave vital assistance on this project. I would particularly like to acknowledge archivist Susan McElrath and the staff at the Bethune Museum and Archives. Their knowledge of archival resources and interest in this project made my trips to Washington, D.C., pleasant and productive experiences.

Thank you to Beverly Jarrett at the University of Missouri Press for seeing the value in this study and for her commitment to the completion of the project. I am also grateful to the anonymous readers who commented on the manuscript. Their comments and suggestions have made this a more valuable study.

Fellowships and research grants defrayed the costs of research trips. I would like to thank the University of Connecticut for providing support through its Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship. The Woodrow Wilson Dissertation Grant in Womens Studies allowed me to complete my research. The College of Social and Behavioral Sciences and the History Department at California State University, San Bernardino provided release time to hasten the transition from dissertation to manuscript.

Three of my colleagues in the History Department deserve special recognition: Kent Schofield for his encouragement, inspirational stories, and unrelenting sense of humor. He is my mentor and became my friend. Ward McAfee, who provided me with evidence of his family connections to Mary McLeod Bethune and who read and commented on the manuscript in its entirety. He is an insightful historian. Last, but not least, Cheryl Riggs, who was there to listen, commiserate, and push me forward when I most needed encouragement. Her commitment to her colleagues, scholarship, activism, and teaching are an inspiration. She is my role model.

I could never have reached this goal without the infinite and unfailing love and encouragement of my familyJennifer, Michael, Alison, and especially my husband, Jim.

Abbreviations

| AW | Aubrey Williams Papers |

| BCC | Mary McLeod Bethune PapersBethune-Cookman College Collection |

| BFC I | Mary McLeod Bethune PapersBethune Foundation Collection, Part I |

| BFC II | Mary McLeod Bethune PapersBethune Foundation Collection, Part II |

| ER | Eleanor Roosevelt Papers |

| FDR | Franklin Delano Roosevelt Papers |

| MCT | Mary Church Terrell Papers |

| MMB | Mary McLeod Bethune Papers |

| NAACP | National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Papers |

| NACW | Papers of the National Association of Colored Womens Clubs, 18951992 |

| NCNW | Records of the National Council of Negro Women |

| NUL | National Urban League PapersSouthern Regional Office |

| NYA | National Youth Administration PapersOffice of Negro Affairs |

Introduction

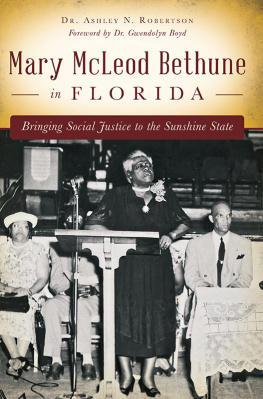

In many ways, Mary Jane McLeod Bethunes life was representative of the lives of many African American women of her time: she was deeply grounded in religion and family, and intensely committed to racial advancement. Yet, Bethune became one of the most important African American women in American political history. She came to occupy a prominent place among a select group of black men and women designated as race leadersmen and women who devoted their lives to advancing African American equality. They became the public voice of the voiceless masses, speaking of the collective identity of people of color and arguing for equal social, economic, and political rights. Bethune was a truly multifaceted and multidimensional race woman. She fought on a variety of levels and used multiple outletseducation, government, and womens associationsin her quest for a more just society. Some black women leaders before her gained more recognition than she achieved in her lifetime, but none before her, and few afterwards, were more effective in developing womens leadership for the cause of racial justice.

Despite her multiple political activities, Bethune has not been recognized as a black political leader. This is attributable in large part to the traditional definition of political activity used by many historians and political scientists: political activity encompasses the actions of individually elected officials and the workings of government. It also rests upon a conventionally accepted and gender-biased idea of a leader as a spokesman, and of politics as voting, electioneering, and office holding. This traditional research defines womens political participation as atypical, seeing women as inadequately socialized into the political process. It ties womens political activism to their social roles as wives and mothers. Women such as Bethune who entered the public arena and fought for substantive reform while remaining grounded in networks of kin, church, and community were left out of political history. As feminist historians have become more interested in political history, they have worked to redefine politics as any activity [that] includes all community work which is oriented to change through multifaceted goals including service, support, public education and advocacy. Political orientation [is adapted] to changing the public agenda through planned and implemented actions. Empowerment is an important part of womens politicization and begins when women change their ideas about the causes of their powerlessness, when they recognize the systematic forces that oppress them, and when they act to change the conditions of their lives. Using this definition, black women who worked through voluntary associations and community organizations became political leaders because they brought particular issues to the attention of politicians and the public. They fought for equal opportunity for African American men and women at a time when America had neither the will nor the desire to make a commitment to racial or sexual equality. Bethune is one such woman who deserves recognition as a political leader based upon the depth and breadth of her political activities.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.