Contents

Guide

Page List

Franchise

The Golden Arches

in Black America

MARCIA CHATELAIN

For Mark Yapelli and his mother, Elaine Desow Yapelli

CONTENTS

Franchise

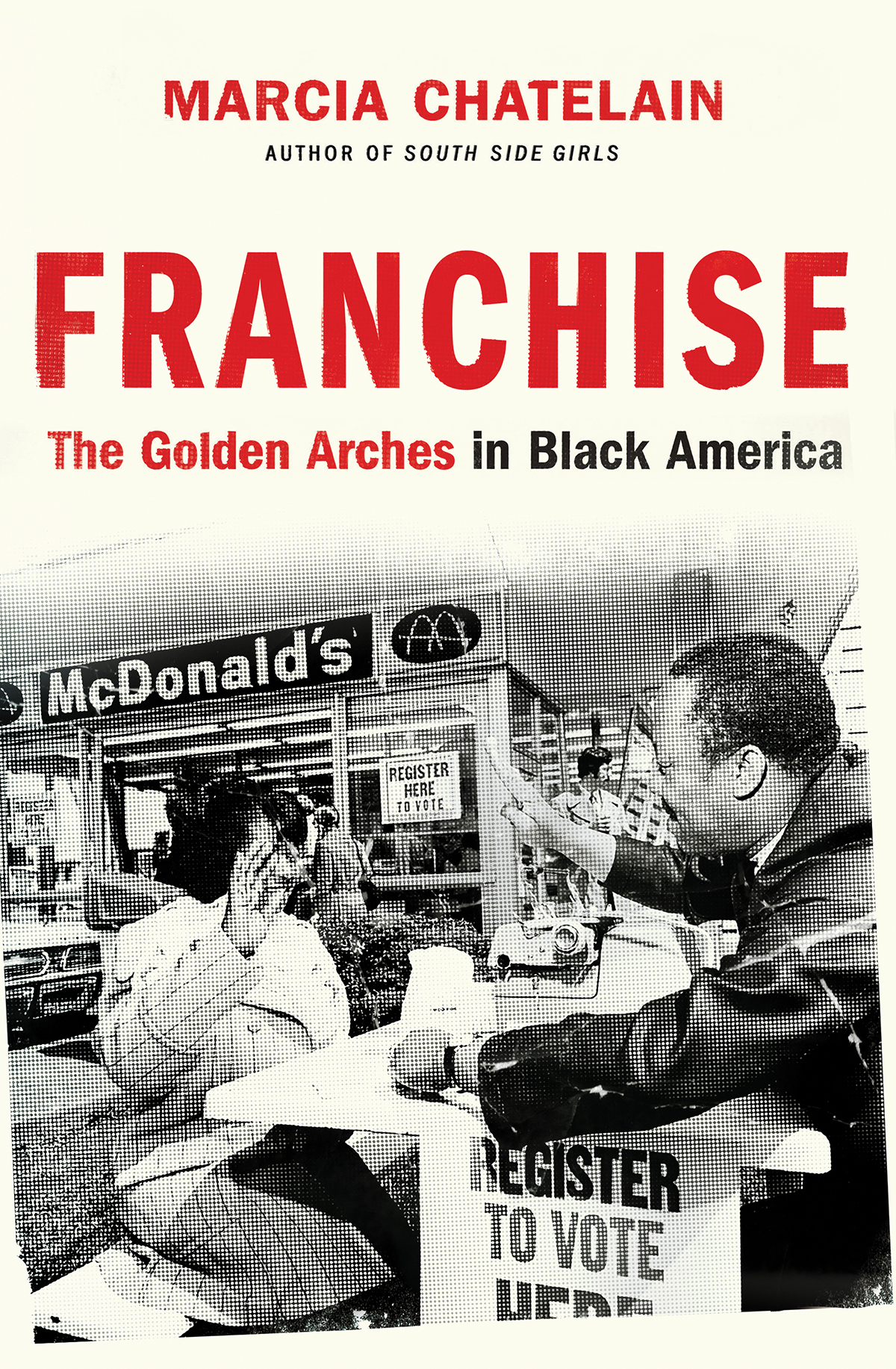

Police and National Guard forces swarmed the McDonalds on Florissant Avenue in Ferguson, Missouri, about one week after police officer Darren Wilson killed Michael Brown, an unarmed teenager, on August 9, 2014. Photo by Scott Olson / Getty Images.

H ands up...

Dont shoot!

Across the streets of Ferguson, Missouri, protesters and mourners shouted the call-and-response dirge in memory of Michael Brown Jr. On August 9, 2014, police officer Darren Wilson shot and killed the teenager while he was walking through an apartment complex with a friend. After six of Wilsons bullets struck the recent high school graduate, his body remained uncollected and uncovered for nearly four hours. Residents captured the morbid scenewith their cellphones and their memoriesand shared them across social media. Browns death and all it representedpolice violence and disregard, racism, and povertycatalyzed the nascent Movement for Black Lives and sparked a global conversation about American justice. By the next evening, seasoned and first-time protesters joined Ferguson residents on the towns main drag, Florissant Avenue. Some carried signs demanding JUSTICE FOR MICHAEL BROWN! Others linked arms with clergy members, belting out civil-rights-era freedom songs. Savvy political leaders and grief-stricken family members sat for interviews with the reporters who traveled to Missouri searching for new angles on the story. A small group of provocateurs brought Molotov cocktails, glass bottles, and matches to the streets. All of these people were met by local and county police, and later the Missouri National Guard, armed with tear gas, rubber bullets, and tanks. The gear was courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defenses 1033 Program, which outfits domestic police forces with weapons unused in Afghanistan and Iraq.

For weeks, traditional news outlets and amateur digital storytellers broadcast updates on the uprising that disrupted life in the town of 21,000. Fergusons landmarks became familiar scenes for the millions who followed the crisis on their televisions and smartphones. Newscasters appeared live in front of the QuikTrip gas station that was burned down the day after Browns death. Facebook and Twitter curated the images of makeshift memorials to Brown in the center and on the edges of Canfield Road where he died. But, of all the places that represented Ferguson in the public eye that summer, the McDonalds restaurant at 9131 West Florissant best symbolized the interplay between racial justice and the marketplace in America, past and present.

The Florissant Avenue McDonalds was both an escape from the uprising and one of its targets. On some days, the McDonalds was a beacon. Reporters found live electrical outlets to charge their computers and Wi-Fi to send emails to their editors. Demonstrators took breaks from marching and ordered cold drinks as the daytime temperature hovered around 80 degrees. Police officers, overheated by their uniforms of domestic war, found air-conditioned relief as they awaited shift changes. In the parking lot, television camera crews arranged tripods. Organizers distributed leaflets. At the counter, cashiers managed their regular duties while also attending to an increase in requests for bottles of milk, used to relieve the sting from the chemicals launched into the late summer sky. The manager kept a television tuned to the news and watched alongside patrons when President Barack Obama addressed the nation about the passions and the anger that had been ignited in Ferguson. The McDonalds was a center of that passion and anger too. One night, two journalists were arrested for trespassing after they questioned why they were being asked to leave an ostensibly open restaurant. On the night of August 17, a crowd broke the front window of the McDonalds; some say they were fleeing another tear gas attack and needed more milk. Others wrote them off as looters. Eventually, calm was restored in Ferguson, and in the recap of what happened in the St. Louis exurb, the Florissant McDonalds was portrayed as a bright spot and an anchor for the community.

The Ferguson moment was not the first time that McDonalds played a major role in a racial crisis. In fact, the Florissant Avenue McDonaldsas a franchise location owned and operated by an African American businessmanis the descendant of a somewhat bizarre but incredibly powerful marriage between a fast-food behemoth and the fight for civil rights. After the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 and the ensuing urban upheavals, the movement for racial justice pivoted its focus toward black business ownership. Hamburger, fried chicken, and taco chains eagerly met the gaze of those interested in using business development as a strategy to quell unrest, and introduced fast-food franchising to inner-city black communities. This book tells the hidden history of the intertwined relationship between the struggle for civil rights and the expansion of the fast-food industry.

The United States is the birthplace of some of the worlds most successful fast-food brands, as well as the home of its most enthusiastic eaters. On any given day, an estimated one-third of all American adults is eating something at a fast-food restaurant. Before fast food became a quotidian fixture of American life in shopping malls, schools, airports, and rest stops, it was an object of curiosity, fascination, and even hope for many black communities.

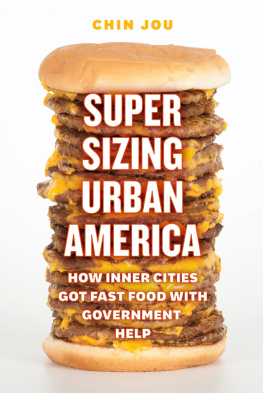

Today, fast-food restaurants are hyperconcentrated in the places that are the poorest and most racially segregated.

In addition to the well-circulated results of health studies, scrutiny of the fast-food industry has come from journalists, documentarians, and even customers. The publication of Eric Schlossers Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal in 2001 and the release of the Academy Awardnominated documentary Super Size Me four years later helped raise awareness about the fast food industrys impact on the health of people of color. In 2002, two teenagers from the Bronx filed a lawsuit against McDonalds for causing their obesity and diabetes. By 2010, when former First Lady Michelle Obama introduced her Lets Move! initiative to promote improved child nutrition and healthier school lunches, the nation was well versed in the vocabulary of healthy eating: whole grains, low fat, and organic. Racialized health disparitiesas well as the dearth of grocery stores in poor communities of colorhave inspired a food justice and nutrition education movement. Farmers markets now occupy empty city lots. Nutritionists visit inner-city schools to teach children the difference between mustard greens and kale. Public service announcements interrupt family-friendly television programs to remind parents to encourage good eating habits at home. The message is clear, but the problems persist.

While health warriors laudably fight an army of trans fats, kids meals, and splashy advertisements, few have considered how exactly fast food became a staple of black diets. Many of the critiques and responses to the impact of fast food on communities of color focus solely on food and not the infrastructure that surrounds food systems. In a response to the failed lawsuit filed by the Bronx teenagers, the