Contents

HARRY TRUMAN

AND THE

STRUGGLE FOR

RACIAL JUSTICE

BOOKS BY ROBERT SHOGAN

Prelude to Catastrophe: FDRs Jews and the Menace of Nazism

No Sense of Decency: The ArmyMcCarthy Hearings

Backlash: The Killing of the New Deal

The Battle of Blair Mountain: The Story of Americas Largest Labor Uprising

War Without End: Cultural Conflict and the Struggle for Americas Political Future

Bad News: Where the Press Goes Wrong in the Making of the President

The Double-Edged Sword: How Character Makes and Ruins Presidents from Washington to Clinton

Fate of the Union: Americas Rocky Road to Political Stalemate

Hard Bargain: How FDR Twisted Churchills Arm, Evaded the Law, and Changed the Role of the American Presidency

Riddle of Power: Presidential Leadership from Truman to Bush

None of the Above: Why Presidents Fail and What Can Be Done About It

Promises to Keep: Carters First 100 Days

A Question of Judgment: The Fortas Case and the Struggle for the Supreme Court

The Detroit Race Riot: A Study in Violence (with Tom Craig)

HARRY TRUMAN

AND THE

STRUGGLE FOR

RACIAL JUSTICE

Robert Shogan

UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KANSAS

2013 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shogan, Robert.

Harry Truman and the struggle for racial justice / Robert Shogan.

page cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7006-1911-5 (alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-7006-2360-0 (ebook)

1. Truman, Harry S., 18841972. 2. African AmericansCivil rightsHistory20th century. 3. United StatesPolitics and government19451953. 4. United States

Race relations. I. Title.

E813.S54 2013

973.918092dc23

2013014064

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication is recycled and contains 30 percent postconsumer waste. It is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481992.

For Ellen Shrewsbury Shogan

In Loving Memory

And for our daughters

Cynthia and Amelia

AUTHORS NOTE

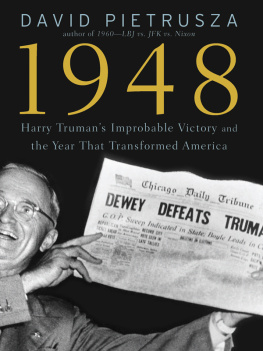

When I first saw Harry Truman in the flesh, nearly a decade had passed since the end of his presidency, and more than that since he had waged his improbable 1948 campaign. But the man who strode into the news room of the Miami News seemed just as forceful as when he took the stage at that long-ago convention in Philadelphia and promised to win the election and make those Republicans like it.

Now it was 1960, another presidential year, and Truman, once again campaigning against the GOP, had taken time to visit South Floridas only Democratic newspaper. He paused at the desk where I was working as telegraph editor, an already antiquated term that meant dealing with the wire service copy that covered national and world news. He glared at me in mock resentment: So youre the fellow who blue pencils all my speeches, he growled.

I confessed my sins, invited him to sit down at my desk, gave him a wire service storyreporting a speech by Harry Trumanalong with a blue pencil, and urged him to edit to his hearts content. He grinned, scribbled for a minute, and withdrew, leaving behind a tic-tac-toe box on the margin of the wire copy.

Later, when it was question time, he proved he had lost none of his old form. Someone asked him to size up Richard Nixon, then well on his way to the Republican presidential nomination. Truman demurred. There is a lady present, he said.

Cant you clean it up? he was asked.

No, Truman said. Every time anything is said about him now it just means another headline for him. It gives him a chance to get out on the front page.

That brief encounter with Truman served as a start in helping me to better understand his performance as president and his place in history. In the years to come, I read more about Truman and often compared him with those who succeeded him in the White House, often to his advantage. I came to recognize those traits that had been underappreciated during most of his time in office by other politicians in both parties, and by many of his fellow citizens. His mind had a sharp partisan edge, grounded in populist ideology. His natural aggressiveness took on depth and breadth from his championship of the underdog. Most important of all, he was a man who had come to terms with himself; this gave him the strength and the courage to face obstacles and odds that others thought would overwhelm him.

Years later, in a conversation with Joseph Biden, then an aspirant for the presidency and later Barack Obamas vice president, Trumans name came up. The political leaders most likely to succeed, Biden said, are those at peace with themselves. Theyre the leaders least likely to let their own insecurities impact on the well-being of the nation. Its the difference between a Harry Truman and a Richard Nixon. A judgment from a partisan, but not necessarily a partisan judgment. Consider the number of leading Republicans, from Gerald Ford to John McCain and even Sarah Palin, who have tried to rub off a bit of Trumans reputation for plain speaking and steadfastness on themselves.

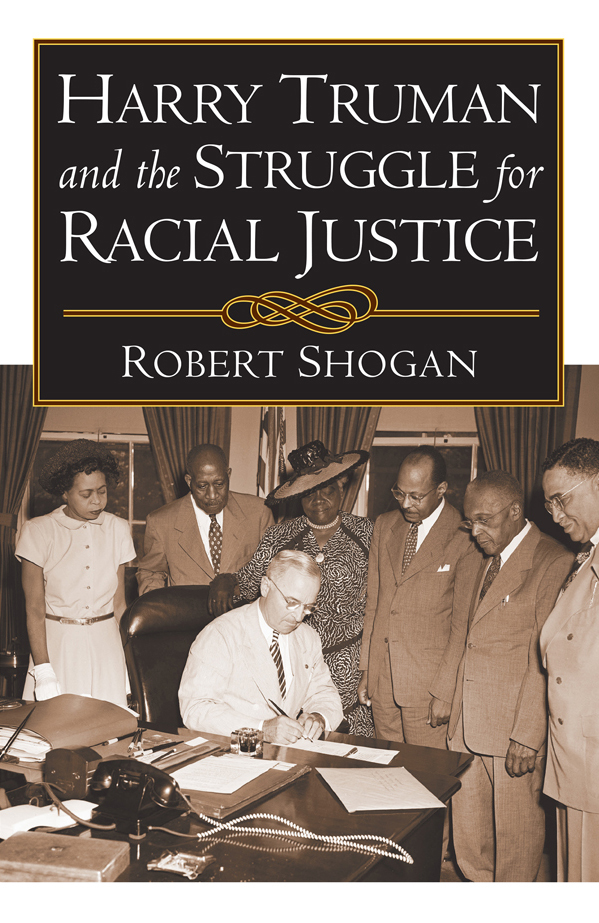

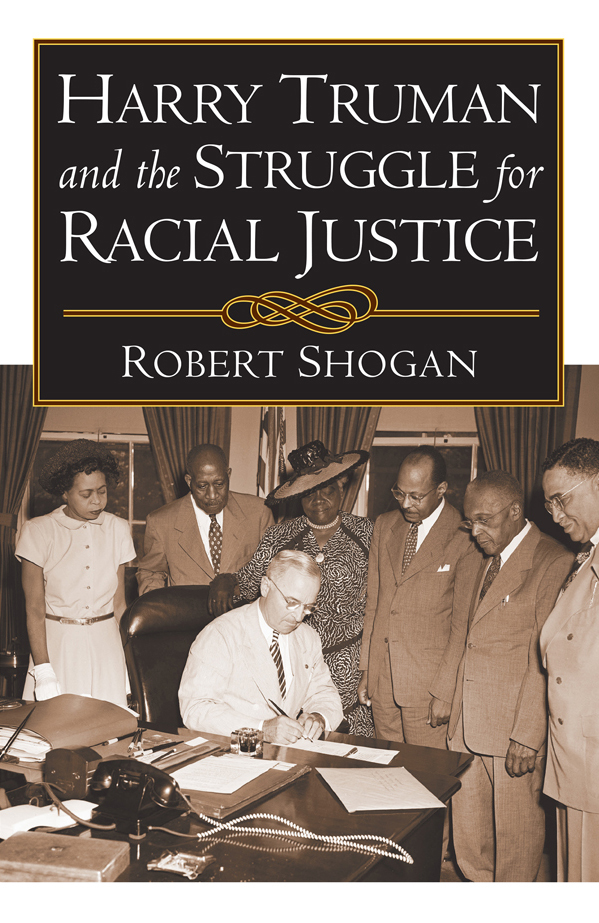

A half century ago when I encountered Truman in Miami, most Americans probably thought of his mobilizing America for the cold war as the outstanding accomplishment of his tenure in the Oval Office. I myself as a political reporter was most intrigued by his 1948 election campaign. But as time passed and the civil rights revolution gained force, I came to believe that his jump-starting that movement represented his most significant achievement and that his self-assurance and self-knowledge helped make that possible.

To be sure, when the drive for racial justice gained steam, Trumans sense of propriety was offended by the tactics of the demonstrators. Characteristically, he made his irritation known. When a trusted friend reminded him that his criticism contravened the record he had compiled in the nations highest office, Truman held his fire. Whether he acknowledged it or not, history makes clear that it was his own actions that had paved the way for the tumultuous drive for equality. That is the story this book tries to do justice to.

I owe an initial debt to Ivan Dee, my former publisher and still my friend, for suggesting that I do a book on Truman. It would have been impossible to write without the resources and support of the Johns Hopkins University library staff, particularly Sharon Morris, Zena Mason, and Feraz Ashraf of the Washington center library. Also invaluable was the assistance of Lorna Grenadier, a retired Justice Department official, who proved to be a tireless and resourceful researcher.

Chevy Chase, Maryland

HARRY TRUMAN

AND THE

STRUGGLE FOR

RACIAL JUSTICE