Introduction THE ELECTION OF 1948

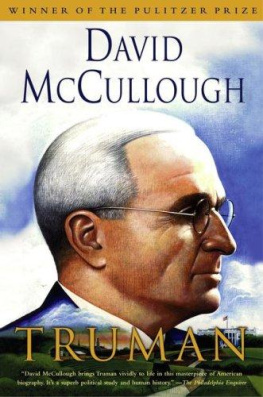

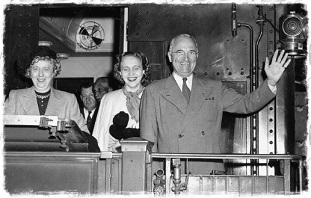

H arry Truman was never supposed to be president of the United States. Born in humble circumstances to farmers in Lamar, Missouripronounced Missour-uh by its residentshe didnt go to college, but instead tilled the land like his father and worked as a speculator, a bank clerk, and the coproprietor of a mens clothing store. These jobs came on either side of a formative stint serving as a captain of artillery in the fields of France during World War I, where Truman impressed his fellow soldiers with his calm demeanor and refusal to join their flight from heavy enemy fire.

Truman survived his military service with nary a scratch, but, like his father, he was not so lucky in business. His Kansas City haberdashery fell victim to the economic tremor of 192021 that preceded the 1929 fiscal earthquake, and his mine investment and attempts to save the family farm fared little better.

As he struggled to make headway in his professional life, Truman turned to a vocation that had fascinated him since he saw the great populist William Jennings Bryan deliver an impassioned speech at the 1900 Democratic National Convention in Kansas City: politics. With close friends staffing his campaigns, Truman was elected as Jackson County judge (in this case, more of an administrative position than a judicial one) in 1933 and, with the backing of influential Kansas City boss Tom Pendergast, as a US senator in 1935. After a moderately successful though not outstanding first term, Truman won re-election to the Senate by just over eight thousand votes in a bitterly contested 1940 election. He then made his mark by chairing what soon became known as the Truman Committee, which saved the government billions by eliminating inefficient wartime contracts and minimizing profiteering.

It was Trumans performance in this role that led to the unlikeliest political event of 1944: this short, fiery, Midwest farm boy who loved to play the piano almost as much as he loved to read, which was almost as much as he liked to talk, found himself as the replacement for Henry Wallace on the Democratic presidential ticket. When Franklin D. Roosevelt defeated his Republican challenger, Thomas E. Dewey, to secure a record fourth term, Truman became vice president.

Just five months after this election, FDR, who had been president for twelve years, had ushered in the New Deal to try to pull the country out of the Great Depression and had brought the United States into World War II after Japan and Germany had given him little choice in the matter, was gone, the victim of a cerebral hemorrhage. There was a cadre of Ivy Leagueeducated, Capitol Hilltested veterans who wanted to succeed him, including Dean Acheson, Burton Wheeler, and Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn, who had all wanted to be FDRs vice president.

Yet, despite the ambitions of these capable suitors, it was Harry Truman, invented middle S initial and all, who took Roosevelts place at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue in April 1945. The Missourians learning curve promised to be especially steep, as he had been vice president for just eighty-two days before taking on this monumental challenge and the mantle of the titan of the age whom he succeeded. When Truman asked Eleanor Roosevelt if there was anything he could do for her on the day FDR passed away, she replied, Is there anything we can do for you? For you are the one in trouble now.

Truman not only inherited Mrs. Roosevelts doubts, but he also faced the scorn of elite Democratic circles on Capitol Hill. Many feared he would be another Andrew Johnson, who was wholly unfit to succeed Abraham Lincoln and whose failure as his successor was punctuated by impeachment in 1868. Liberals criticized him for not being liberal enough despite his continuation of Roosevelts policies, some of which he carried further. New Dealers and FDR loyalists thought him uneducated and unprepared, ignoring his keen intellect and stellar work as a two-term senator. Conservatives dismissed him as a Kansas City machine pol and a less capable FDR replacement who would merely extend the New Deal reforms they so detested.

Unrealistically low expectations aside, Truman also faced a host of domestic problems and international crises, which arguably amounted to a more daunting task than that of any president save his predecessor, Washington, Wilson, and Lincoln, men who, many believed, Harry Truman was not fit to shine the shoes of, let alone follow into power.

Yet despite his perceived shortcomings and because of fate, Truman sat down with Churchill and Stalin at the Potsdam Conference in July 1945, just weeks after he became president. There he attempted to broker peace and check the advance of Russian communism across Europe and Asia. It was he who made the fateful decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki the following month in which more than one hundred thousand Japanese died instantly. And it was he who, with the war won, confronted the housing shortage, widespread industrial strikes, and myriad other problems that plagued America in the early postwar period with a decisiveness and determination that should have endeared him to his critics.

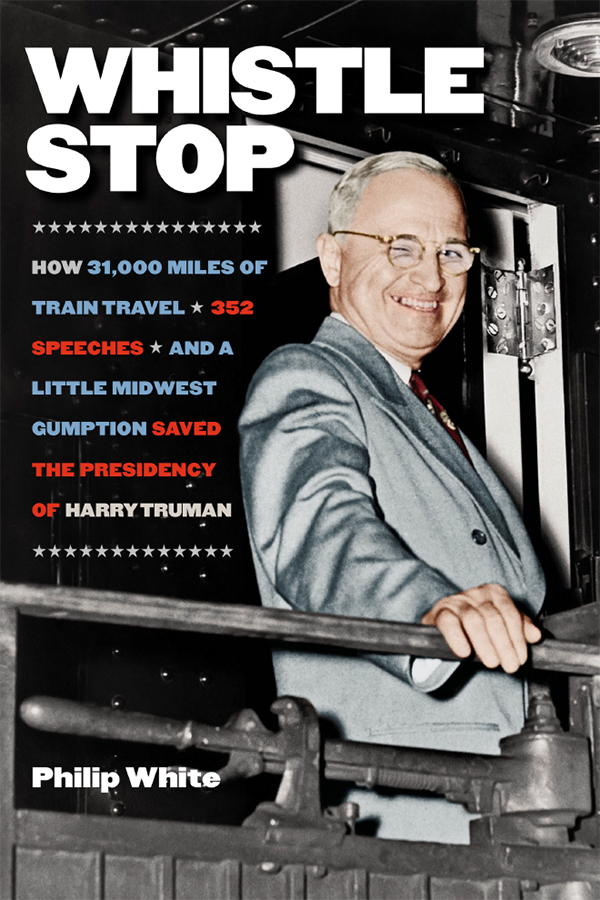

In the ensuing two years, he presided over the Truman Doctrine for containing communism and implemented the Marshall Plan for creating a buffer against it by rebuilding Western Europe, and then, in 1948, he stared down Stalin over the Berlin Blockade while presidential rival Henry Wallace and other detractors urged him to tuck tail and run. And, in his most controversial policy move to date, Truman announced a courageous new civil rights program that delighted progressives but horrified segregationists in the South. By then, early 1948, it was an election year in the United States and the battle lines had been drawn. Yet even these were not as simple to deal with as they had been for FDR.

The desertion by the southern Democrats was just one of the splits in his party. Henry Wallace, the man who had resigned from his post as secretary of commerce at Trumans request over his relentless criticism of George Marshalls foreign policy, and particularly Americas stance on the Soviet Union, now led the breakaway Progressive Party. Wallace, an able politician who for a time had been one of FDRs favorites and who was by any measure an extraordinary speaker, was not a candidate to be underestimated, and now he threatened to divert left-wing votes away from the president at a time when Truman needed every one he could get. This even though Eisenhower, like Truman, was a plainspoken midwesterner without Ivy League credentials, a ritzy upbringing, or an achievement-studded career in politics.