Table of Contents

Introduction

IT WAS LATE in the afternoon, and there wasnt much more to say that hadnt already been said. Harry Truman could stay in his suite at the Muehlebach Hotel in Kansas City, glued to the returns and forced to listen to those radio people banter about what we could all look forward to during the Dewey administration. He could confront the downcast faces of his staff as they prepared to wait for the results that would show just how badly he had lost. But he didnt want to deal with the crowd of reporters and well-wishers who were gathered in the lobby. They had those fragile frantic smiles of people who knew that only false optimism was keeping them from tears. To them, he wasnt President Truman, he was Harry, one of them, and they couldnt bear what was about to happen. But as much as he wanted to be with them, he had something they didnt: faith. He believedno, he knewthat the country would rally behind him. And when he saw in the faces of his advisers that not many of them shared his quiet, and what must have seemed to them foolish, confidence, he knew that he had to get out of there.

The Secret Service came and whisked him away to the Elms Hotel, across the Missouri River in Excelsior Springs. And there Harry settled in for the evening. That night there would be no poker playing with the boys from Missouri, no rough-and-tumble joking, no cigars and whiskey. Instead, Harry had a mineral bath and a rub-down, a light supper and a glass of buttermilk, and turned on the radio to hear the peculiar staccato voice of H.V. Kaltenborn tell the nation that, based on the early count, Truman was ahead but certain to lose once the results from Ohio and California were known. So Harry turned off the radio and went to bed without a drink. At least thats what all the papers reported, and what Charlie Ross, his loyal press secretary, stated.

Truman hadnt expected to be president in the first place. Most of his life had consisted of unforeseen developments. Early on, he thought hed be a farmer, but though hed worked hard on his land, he found that he didnt want to live that way forever. He thought that hed be a haberdasher, but his store went bankrupt. Hed commanded men in battle in Europe, and done it well, but that wasnt a career. He never imagined that hed be a county judge or a United States senator, but he was elected nonetheless, having been urged to campaign for the senate by his longtime patron, boss Tom Pendergast of Kansas City. Having won once, he won again, and in his second term, after a quiet career as a loyal Democratic backbencher who shone briefly as chairman of a committee investigating wartime profiteering by big business, he was selected by party bosses to be Franklin Roosevelts running mate at the convention in 1944. And then, in the most surprising turn, Roosevelt died in April 1945, and Harry Truman became president.

Truman was one of those rare men who seemed content with himself and with his life. He enjoyed being a farmer; he liked being a senator; and he didnt much mind being president. He kept his hair neatly slicked back, dressed snappily in double-breasted suits, and wore thick glasses to compensate for his terrible eyesight. He adored his wife, and doted on his daughter, and if he sometimes felt that his job was too big for him, he managed to carry it off with at least as much authority and panache as most of his predecessors. After a tumultuous three years in the White House, Truman ran again, because there was no reason not to; and besides, he felt he was doing just about as good a job as any other Democrat could and a better job by far than any Republican might. And though the campaign had started on a low note, he assumed that it would all work out in the end, win or lose. The thing was, he didnt think the American people would vote him out of office. He felt that hed done well, all things considered, and he was pretty sure that the voters would come to the same conclusion.

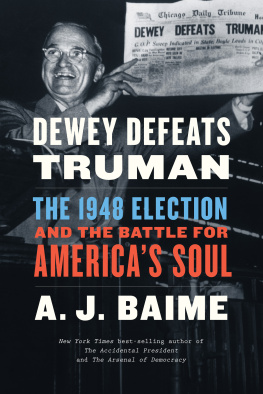

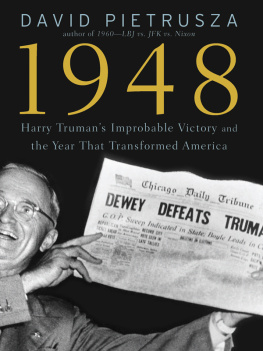

It turned out that Harrys faith was justified. Around 4 a.m., it happened: the returns indicated that he would win. By early morning, he was dressed and back at the Muehlebach in Charlie Rosss hotel room. The news was good, he said, and so I decided to come in to town. Stalwart campaign manager that he was, Ross blinked in astonishment at the sight of his cheerful boss, the once and future president of the United States, bouncing playfully around the room. By 10 a.m. on November 3, radio announcers throughout the country said words that none of them had thought they would utter: Truman won. Truman had beaten Thomas E. Dewey. The press and the pollsters would be dining on crow for weeks. Even his own staff were chagrined that they ever had doubts, but frankly, they just hadnt thought that victory was possible. There was no way that Truman could pull that particular rabbit out of that particular hat, no matter how much he smiled and gave em hell. But he did, and for Truman, the explanation was simple: Labor did it. But the reasons went deeper than that, and for all of labors support, he had lost Michigan and New York and New Jersey and Pennsylvania and nearly lost Ohio and Illinois. And what he had won, hed won dirty. In elections as in street fights, rules were for losers. With the ChicagoTribune and Colonel Robert McCormick publishing the worlds most incorrect headlineDewey Defeats TrumanTruman was going to have some fun in the weeks ahead.

That night he told the crowds who gathered in Independence, Missouri, at the courthouse square that he was just a favorite son who had done well. He just wanted to be treated like any other Independence taxpayer, no special favors, no hoopla, just Harry S Truman. For the next two days, as the train with his private car, the Ferdinand Magellan, made its way back to Washington, D.C., Truman took every opportunity to stop and greet people at stations along the way, an encore to the whistle-stops that had helped cement his victory. And wherever he went, he took a copy of the Tribune with him, and held it up with a grin as wide as the Kansas prairie, as if to say that the last laugh truly was his.1

FIFTEEN HUNDRED miles away in New York, Thomas Dewey was smiling as well. If you looked at him for just a moment, you couldnt have told whether hed won or lost. It was the same slight smile that hed worn for much of the campaign, and for much of his political career. It was a perfect smile, one that lacked only spontaneity and seemed to suit every occasion. Theres Dewey at home for a quiet evening with the family, sitting on his couch in a suit and tie, playing with the old dog. Theres Dewey on the farm in Pawling, New York, with the cattle in the background. Theres Thomas Dewey, crimefighter extraordinaire, wunderkind governor of New York. It was Thomas Dewey, not really Tom. Youd never ask him to give em hell.

He was a good son who wrote regularly to his mother in Michigan, always addressing his letters Dear Mater. For Dewey, life had been charmed. He knewas the pollsters and the pundits knew and the radio commentators and the man on the street and everyone back in Owosso, Michigan, knewthat Thomas Dewey would beat Harry Truman on November 2, 1948. They knew that at the age of forty-six, he would become the youngest president since Teddy Roosevelt, and the first Republican in the White House since Herbert Hoover slunk away in Depression disgrace. He knew from early September that the race for the White House was all but over, that Truman should have had the good grace to concede rather than go on the warpath. During the final weeks of the campaign, Dewey withstood a ferocious Truman charge, and he was vilified by his opponents. But he refused to join Truman in the gutter. He wasnt going to risk alienating voters and, whats more, he wasnt going to sully himself with the crude campaign being run by his opponents. If ever there was a man comfortable on the high road, Thomas Dewey was that man.

Next page