Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant

from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Copyright 1999 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Club Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

04 03 02 01 005 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Donaldson, Gary.

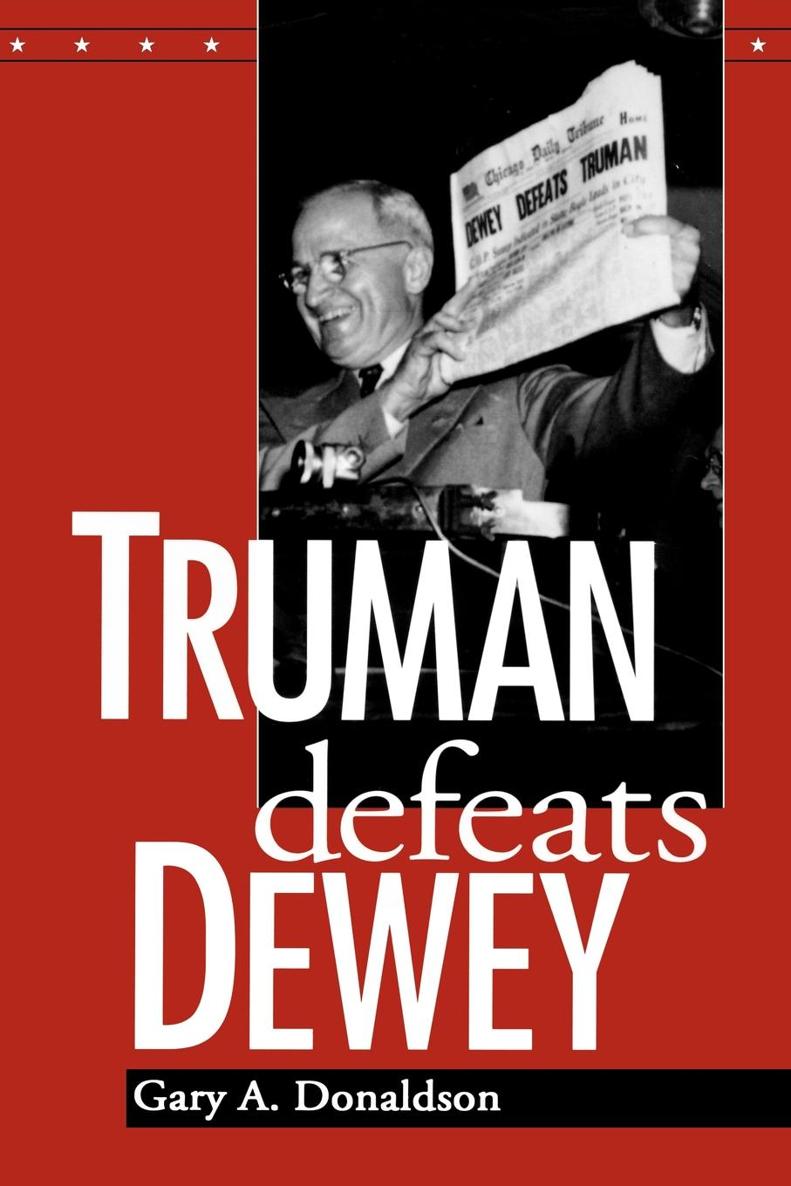

Truman defeats Dewey / Gary A. Donaldson.

p.cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8131-2075-6 (alk. paper)

ISBN 0-8131-9002-9 (pbk : alk. paper)

1. PresidentsUnited StatesElection1948. 2. Truman, Harry

S., 1884-1972. 3. Dewey, Thomas E. (Thomas Edmund), 1902-1971.

I. Title.

E815.D661998

324.9730918dc2198-24424

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Acknowledgments

I wish to acknowledge people who assisted in the completion of this book. I received several small travel grants from the Bush-Hewlett Foundation, and without them this work could never have been completed. The grants were awarded through Xavier University, and I am indebted to those at Xavier who saw promise in my scholarship. I am particularly indebted to the members of the History Department at Xavier for their encouragement. I also wish to thank the archivists at several libraries, including those at the Truman Library, the libraries at the University of Iowa, the University of Rochester, the University of Wisconsin, and Clemson University. Without their kind assistance, the research for this work would have been impossible. Last, I thank my family for undying support and assistance. Thank you for being quiet.

Introduction

Every four years at election time the image of Harry Truman is trotted out by the popular press, and comparisons are made between todays candidates and the no-nonsense president from Independence, the man who pulled off the greatest of election upsets against all the odds and against the predictions of all the pundits and pollsters. The nations interest in the election is understandable. The election of 1948 was a spectacular upset and a great victory for Truman and the Democrats. It was also, in many ways, the beginning of a new, modern political era in American history. By election day, November 2, Truman and his advisers and campaign strategists had put together a large, loose-fitting, temporary coalition that pushed the president over the top in the balloting. Everyone, it seems, except the president himself, was surprised by the outcome. Even Bess Truman doubted that her husband could win.

This 1948 Democratic coalition was made up of many of the main parts of the old New Deal coalition that had kept Roosevelt and the Democrats in power through the decade of the mid-1930s to the mid-1940s. But the coalition that formed around Truman in 1948 was also very different. The times had changed, new factors had been introduced into the American political scene, and, of course, many of the players were different. The war and then the Cold War changed America. The nations confrontations with the Soviet Union altered the nature of politics and even the way Americans voted. On the left, for instance, several of the Democratic partys old coalition groups broke apart over the issue of communism; communism also changed voting patterns in such important groups as the progressives, the liberals, and labor.

The coalition was different after the war also because several of the groups that had supported Franklin D. Roosevelt were not nearly as important to Truman and his strategists, whereas groups that were of little significance to Roosevelt emerged after the war years as power brokers in the party. The South was the most obvious loser. A major player in the Roosevelt administration, the South had been a chief benefactor of New Deal programs, and every four years the region had returned the favor with reliable votes. But after the war the Souths small electoral numbers foretold a future of weakening power within the party structure, particularly in close elections. Truman and his political strategists believed that the South was safely Democratic. It became clear immediately after the war that a black-urban-liberal coalition in the Northeast, Midwest, and California made for more lucrative political ground to plow than the Old Confederacy. These groups, particularly African Americans, whose changing voting patterns had placed them in a position to demand a hearing from the federal government and the Democratic party, gained new power. The changing political situation forced the Democrats, for the first time, to choose between the segregated South and the growing African-American voting strength in the northern cities.

The left was also out. Once a powerful wing in the Democratic party, the left had been the backbone of the New Deal. Henry Wallace, Harold Ickes, Henry Morgenthau Jr., and other New Dealers were the policymakers who kept the New Deal on line and running. Truman and the postwar Democratic party had no use for these men. Truman called them crackpots. Wallaces lack of appeal in 1948 more than anything else made it clear that the Democratic partys left wing was gone and that the party was now controlled by those who leaned toward the center of American politics.

Organized labor also had been a strong and important part of the New Deal coalition, and Roosevelt had aided its cause to gain its support. The Wagner Act, which gave labor the right to organize, was the payoff it received for supporting the administration. In addition, as the New Deal sought to aid the lot of the common man, wage earners, along with farmers, benefited the most. Although labor remained inside Trumans coalition in the 1948 election, it had changed as well. Labor was divisive after the war, and it had begun to purge itself of its far left and move toward the center along with much of America.

Trumans problems with labor revolved mostly around the nature of the postwar economy, which differed greatly from the economy of the prewar years. Truman had to grapple with the problems of an economy of inflation. Roosevelt had fought an economic depression. The answers to Americas economic problems were the direct opposite in each case. Truman could not maintain political support, as Roosevelt did, by bestowing economic programs to the advantage of specific groups. In fact, Truman was forced to restrain economic growth in various sectors of the postwar economy, particularly in labor and industry. Moreover, American workers had been deprived of economic prosperity during the Depression, and they had sacrificed further to win the war. After the war, most earnings for factory workers had fallen below prewar levels. When, in 1945 and 1946, Truman attempted to keep the economy in check by holding down wage increases along with other inflationary practices, he alienated labor.