Truman Fires MacArthur

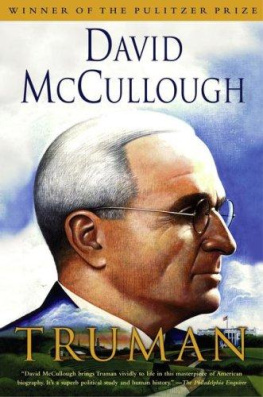

(ebook excerpt from Truman)

David McCullough

Simon & Schuster

New York London Toronto Sydney

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

This is an excerpt from Truman copyright 1992 by David McCullough

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

This Simon & Schuster ebook edition June 2010

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or business@simonandschuster.com

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Designed by Eve Metz

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition of Truman as follows:

McCullough, David G.

Truman/David McCullough.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Truman, Harry S., 18841972.

2. PresidentsUnited StatesBiography.

I. Title.

E814.M26 1992

973.918 092dc20 [B] 92-5245 CIP

ISBN: 978-1-4516-1822-8

An intemperate general. An unpopular war. A military and diplomatic team in disarray.

Those are the challenges President Obama has faced as he attempts to make a success of U.S. involvement in Afghanistan. They are also the challenges President Truman surmounted in the winter of 1950 as he began managing a war in Korea that risked becoming bigger and more costly. It was the first significant armed conflict of the Cold War: U.S. troops under the command of General Douglas MacArthur came to the aid of the South Koreans after North Korea invaded. When Communist China entered the conflict on the side of the North Koreans, the crisis seemed on the verge of flaring into a world war. Truman was determined not to let that happen. MacArthur kept urging a widening of the war into China itself and ignoring his commander in chief. On April 11, 1951, after MacArthur had shot his mouth off, as one diplomat put it, one too many times, Truman fired him.

The story of their showdownone of the most dramatic in U.S. history between a commander in chief and his top soldier in the fieldis captured in all its detail by David McCullough in his Pulitzer Prizewinning biography Truman, and presented here in a ebook called Truman Fires MacArthur (ebook excerpt of Truman), which was the headline carried in many newspapers around the country the next day.

* * *

The winter of 1950 was a dreadful passage for Truman. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Omar Bradley was to call the months of November and December among the most trying of his own professional career, more so even than the Battle of the Bulge. For Truman it was the darkest, most difficult period of his presidency.

The off-year elections, though nothing like the humiliation of 1946, were a sharp setback for the Democrats and in some ways extremely discouraging. Local issues were decisive in many congressional contests, but so also were concerns over the war in Korea and what Time referred to as the suspicion that the State Department had played footsie with Communists. The Korean death trap, charged Joe McCarthy, we can lay at the doors of the Kremlin and those who sabotaged rearming, including Acheson and the President, if you please. Senator Wherry said the blood of American boys was on Achesons shoulders. In Illinois, Republican Everett Dirksen, running against Senator Scott Lucas, the Democratic majority leader, said, All the piety of the administration will not put any life into the bodies of the young men coming back in wooden boxes.

McCarthy, who was not up for reelection, had vowed to get Lucas and Millard Tydings both, and both senators, two of the administrations strongest supporters, went down in defeat. Tydings especially was the victim of distortions and lies. In the campaign in Maryland, McCarthy and his aides circulated faked photographs showing Tydings chatting with Earl Browder, head of the Communist Party. In the California Senate race, Richard Nixon defeated Helen Gahagan Douglas by calling her, among other things, pink down to her underwear.

One of the saddest things of all, Truman told a friend, was the way McCarthyism seemed to have an effect. In thirty years of marriage, Bess Truman had seldom seen him so downhearted, blaming himself for not keeping the pressure on McCarthy.

Fifty-two percent of the votes cast in the country had gone to the Republicans, 42 percent to the Democrats. The Democrats still controlled both houses of Congress, but the Democratic majority in the Senate had been cut from twelve to two, in the House from seventeen to twelve. And though Truman had taken no time for campaign speeches, except for one in his own state, in St. Louis on the way home to vote, the outcome was seen as a personal defeat. In the Senate, for all practical purposes, he no longer had control. Furthermore, Arthur Vandenberg, upon whom Truman had counted so long for nonpartisan support, was seriously ill and not likely to return.

Some Republicans interpret the election as meaning that you should ask for the resignation of Mr. Acheson, a reporter said at his next press conference.

Mr. Acheson would remain, Period, said Truman.

Was he blue over the elections? Not at all, he said. And in truth, the elections were a minor worry compared to what was happening in Korea.

That Chinese troops were in the war was by now an established fact, though how many there were remained in doubt. General Douglas MacArthur estimated thirty thousand, and whatever the number, his inclination was to discount their importance. But in Washington concern mounted. To check the flow of Chinese troops coming across the Yalu, MacArthur requested authority to bomb the Korean ends of all bridges on the river, a decision Truman approved, after warning MacArthur against enlarging the war and specifically forbidding air strikes north of the Yalu, on Chinese territory.

Another cause of concern was MacArthurs decision, in the drive north, to divide his forces, sending the Tenth Corps up the east side of the peninsula, the Eighth Army up the westan immensely risky maneuver that the Joint Chiefs questioned. But MacArthur was adamant, and it had been just such audacity after all that had worked the miracle at Inchon. Then there were those, wrote Matthew Ridgway, who felt that it was useless to try to check a man who might react to criticism by pursuing his own way with increased stubbornness and fervor.

With one powerful, end-the-war offensive, one massive comprehensive envelopment, MacArthur insisted, the war would be quickly won. As always, he had absolute faith in his own infallibility, and while no such faith was to be found at the Pentagon or the White House, no one, including Truman, took steps to stop him.

Bitter cold winds from Siberia swept over North Korea, as MacArthur flew to Eighth Army headquarters on the Chongchon River to see the attack begin. If this operation is successful, he said within earshot of correspondents, I hope we can get the boys home for Christmas.

The attack began Friday, November 24, the day after Thanksgiving. Four days later, on Tuesday, November 28, in Washington, at 6:15 in the morning, General Bradley telephoned the President at Blair House to say he had a terrible message from MacArthur.