Sixty-eight years old and in good health when he left the White House in January 1953, Harry Truman lived for almost twenty more years. And although in time he would recede from the minds of most Americans, he never entirely fell from view. He was too strong a personality and too devoted to the national interest to remove himself totally from public deliberations.

In the first years after leaving office, he remained an outspoken partisan. He disliked Dwight Eisenhower and his conservative economic policies and took every opportunity to denounce them as throwbacks to the bad old preNew Deal days. He saw Eisenhower as the captive of big business interests more intent on serving themselves than the national well-being. His tensions with the Eisenhower administration were so intense that he refused to attend a White House dinner in 1959 honoring Winston Churchill, for whom he continued to have the highest regard.

Trumans antagonism to Eisenhower and the Republicans moved him to actively oppose them in the 1956 election. Believing that Adlai Stevenson would be no more successful than he had been in 1952, Truman publicly supported New York governor Averell Harriman for the Democratic presidential nomination. But when Stevenson became the partys nominee and made Estes Kefauver hisrunning mate, Truman muted his differences with both men by endorsing the ticket and campaigning for them in the fall.

Eisenhowers reelection by a wide margin frustrated Truman, but he took pleasure in continuing Democratic Party control of the House and the Senate. When a recession and traditional midterm losses for the party controlling the White House made 1958 look like a good year for the Democrats, Truman threw himself into the political struggle for congressional dominance. Refusing to accept that at seventy-four he might not be able to stand the rigors of another campaign, he spoke in twenty states for the partys candidates. Democratic victories expanded the partys margin in the Senate to a lopsided sixty-four to thirty-four and increased the advantage in the House to nearly two to one. The gains hugely pleased him.

The 1960 election impressed Truman as a great opportunity for the Democrats to regain the presidency. Eisenhowers second term had been a period of setbacks in the cold war: the Soviets success in launching Sputnik , the first satellite to orbit the earth, in October 1957, gave Moscow an apparent advantage in intercontinental ballistic missiles; and a U.S. spy plane, the U-2, was shot down over the Soviet Union in May 1960, which scuttled a summit meeting between Eisenhower and Nikita Khrushchev. Moreover, continuing domestic difficulties with the economy made the Republicans vulnerable to defeat.

Truman worried, however, that the candidacy of Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts would jeopardize the Democrats chances. He believed that Kennedy at forty-three was too young and inexperienced and that his Catholic identity would lead to his likely defeat in November, resulting in Vice President Richard Nixons election as president. Because he despised Nixon as an unprincipled opportunist who had questioned his patriotism, Truman felt compelled to oppose Kennedy openly. He also feared the influence of Kennedys father, Joseph Kennedy, whose affinity for isolationist foreign policies, antagonism to Franklin Roosevelt, and support of Joseph McCarthy made Truman eager to keep him asfar from the White House as possible. Its not the Pope Im afraid of, Truman said. Its the pop.

In May, after Kennedy had won a crucial primary in West Virginia that made him the front-runner for the Democratic nomination, Truman endorsed Stuart Symington, the senior senator from Missouri, and hoped that he or Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson of Texas would become the partys nominee. In July, on the eve of the convention, with Kennedy the predicted winner, Truman held a press conference to complain that the convention was rigged in Kennedys favor and urged Kennedy to stand aside until he was experienced enough to deal with the crucial foreign policy challenges certain to face the next president. Truman also announced that he would not attend the convention in Los Angeles as a protest against the machinations that seemed to have settled the outcome before the delegates met.

Although Trumans public opposition offended Kennedy and his supporters, it was ineffective. To win Trumans support and unite the Democratic Party, Kennedy followed his nomination by placing a placating phone call to the former president. Flattered by the attention and as eager as ever to beat Nixon, Truman readily agreed to help in the campaign. Kennedy then cemented Trumans backing with a visit to Independence for a face-to-face meeting. Truman followed through on promises to speak for Kennedy by traveling to nine states, where he gave thirteen speeches and put in long days that would have exhausted someone much younger than seventysix years old.

After his election, Kennedy won Trumans enthusiastic approval by making public demonstrations of personal regard for the partys senior statesman. An invitation to meet with Kennedy in the Oval Office the day after his inauguration and a formal dinner in November 1961 to honor Truman, who had never been invited to the White House during Eisenhowers eight years, relieved some of Trumans doubts about the young mans suitability for the presidency. Kennedys support of domestic initiatives that echoed Trumans earlierproposals for national health insurance, federal aid to education, and civil rights endeared him as well. More important, Kennedys success in resolving the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 persuaded Truman that Kennedy was entirely worthy of the office.

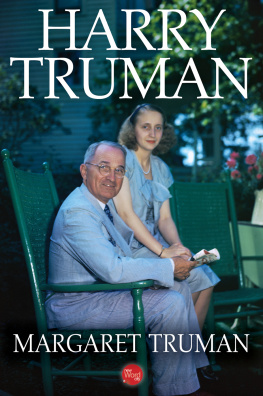

Nineteen sixty was Trumans last major participation in a political campaign. He had involved himself against the advice of his wife and daughter. Bess had urged him to leave current political battles to younger men. Margaret had told him that he was just like his two-year-old grandson, Truman said: He runs all the time, never walks, and talks all the time and never says anything.

Kennedys election persuaded Truman to move to the political sidelines. This did not preclude ceremonial occasions such as attending Kennedys funeral in 1963. Nor one in 1965, when Lyndon Johnson came to Independence to sign a Medicare bill, which was seen as a significant advance toward Trumans unfulfilled proposal for national health insurance. Nor did it preclude an address to the Senate on his eightieth birthday when Democrats and Republicans alike paid Truman tributes that brought tears to his eyes.