Harry S. Truman, the man from Missouri who served as the thirty-third president of the United States, has been the subject of many books. Historians, political figures, friends, foes, and family membersall have sought to characterize, understand, and interpret this figure who continues to live in the minds and imaginations of a broad reading public. The Give Em Hell Harry Series is designed to keep available in reasonably priced paperback editions the best books that have been written about this remarkable man.

Preface

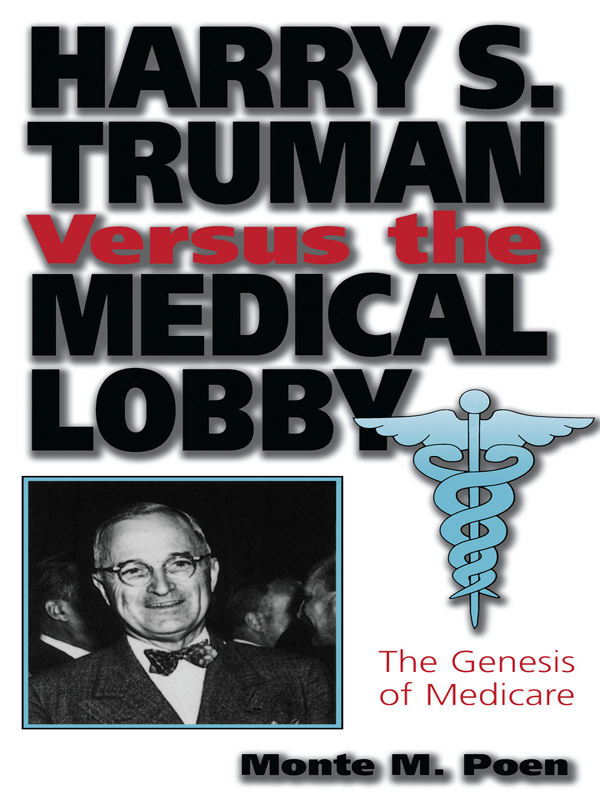

I have had some bitter disappointments as President, reflected Harry Truman after leaving office, but the one that has troubled me most, in a personal way, has been the failure to defeat organized opposition to a national compulsory health-insurance program. Truman had promoted enactment of such a program throughout nearly two full terms as president only to find bills incorporating the scheme bottled up in congressional committees and his advocacy of health security labeled socialistic and un-American by forces led by the country's richest and most influential postWorld War II lobby, the American Medical Association. But, although nearly sixty-nine years old when he retired from public life in 1953, Harry Truman lived to see inauguration of medicare twelve years later, during the Johnson administration. True, medicare, a government health insurance program for the aged, fell far below the universal, comprehensive coverage Truman had sought initially, but it represented a significant benchmark in a movement for health security that, only nowthree decades, six presidencies, and thirty-two congressional sessions after Truman first gave it his presidential endorsement in 1945has reemerged as a serious proposal vieing for congressional approval and national implementation.

Hence, this volume is not a study of failure, at least not from the long-term perspective of those who, like Harry Truman, identified themselves with the branch of American liberalism that promoted national acceptance of social-justice programs designed to provide minimal economic security for alla reform tradition dating back to the rural Populist agitation of the 1880s and 1890s, redefined and applied to the urban setting during the Progressivemovement of this century's first decades, and extended further during the depression thirties by Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal. Rather, this is a study of one aspect of Harry Truman's domestic leadership and the political conflict it produced, which was due to the fact that America has another tradition than Truman's, one that emphasizes the virtues of an individualistic, libertarian society placing a premium upon self-help and favoring, when absolutely necessary, private and local philanthropy rather than federal governmental assistance. Throughout most of our history this latter tradition has dominated; to most it is the American Way, a condition of normalcy, in the truncated lexicon of Warren G. Harding. And it was Harry Truman's fate to be president during a time when the forces of conservatism, assisted greatly by a fragmented and competitive American legislative system (which by its very nature resists quick acceptance to change), had regained their strength following more than a decade of centralized governmental, especially presidential, direction of national affairs.

What political influences and personal motivation brought Harry Truman to champion national health insurance? How did the thirty-third president of the United States conduct himself as a policymaker and advocate of legislative reform? Why did promotion of the health security idea arouse such an impassioned (and expensive) organized reaction by medical practitioners and their allies? What factors contributed to organized medicine's immediate, if not ultimate, victory over health reformers during the Truman presidency? When I first broached these questions in my doctoral dissertation written a decade ago at the University of Missouri, I concluded that Harry Truman's advocacy of national health insurance, while sincere, was woefully inadequate. I have changed my mind. Additional research and reflection have convinced me that no matter how sincere and skillful, no president, given the restraints placed upon him during this postwar era, could have surmounted the intellectual and institutional obstacles barring enactment of a comprehensivehealth security program. While still acknowledging Truman's ineffective performance as a legislative salesman before the public, I have become more appreciative of what skill he did demonstrate in his dealings with Capitol Hill over the health issue. As to the role played by organized medicine, I have become more impressed by the medical community's ability to influence public opinion and by the power enjoyed by lobbies in general to block consideration of domestic reform legislation even when public opinion favors its passage. More than anything, I have become more aware of the complexities of human personality and motivation, certainly of the inharmonious, even abrasive character of executive-legislative interaction in our national government, not only during Truman's presidency, but throughout most of our recent political history.

Because their manuscript collections and private records have been opened to researchers, those individuals and groups who fought in behalf of medical reform have granted me the clearest view of their motives, methods, and aspirations. Conversely, with few exceptions, unpublished materials held by those who led the opposition to Truman's health program were not made available. Nevertheless, I have tried to present a balanced and objective analysis of their position and legislative strategy by using the Journal of the American Medical Association along with other published accounts of organized medicine's activities during the half-century contest over medical reform.

Acknowledgments must begin with a special thanks to Franklin D. Mitchell of the University of Southern California, a longtime friend and counselor, for reading the entire manuscript and proffering many valuable and challenging suggestions concerning clarity of expression and scholarly precision. Richard S. Kirkendall of Indiana University, under whose direction I originally explored this subject in dissertation form, and Alonzo L. Hamby of Ohio University also rendered valuable critiques on the manuscript. Two grants-in-aid from the Harry S. Truman Library Institute and a grant from the NorthernArizona University Institutional Research Committee made possible the bulk of my research. Among the many people who helped facilitate my investigation, I am appreciative especially of assistance given by former Truman Library Director, the late Philip C. Brooks, and his staff; Elizabeth B. Drewry, Director of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, and staff; John E. Wickman, Director of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, and staff; Josephine L. Harper, Manuscripts Curator of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin; and by the many competent people at the National Archives and the Library of Congress. J. Joseph Huthmacher of the University of Delaware and Donald P. Chvatal of the University of Montana helped me find my way through the Robert F. Wagner Papers and the James E. Murray Papers respectively. U.S. Rep. John D. Dingell and Mr. Oscar R. Ewing were most cooperative, allowing me access to private papers in their possession, as was Mary W. Lasker, who permitted me to draw upon her Columbia University Oral History reminiscences. I also want to acknowledge the generous assistance given me by President Harry S. Truman, Michael M. Davis, and Isidore S. Falk, all of whom granted me personal interviews, and by Samuel I. Rosenman, Arthur J. Altmeyer, Mary W. Lasker, and Wilbur J. Cohen, who after reading various sections of the manuscript wrote me expressing their views concerning the history's validity. Richard Dalfiume of the State University of New York at Binghamton, also deserves a thank you for sharing knowledgeable insights gained through his own investigation of the health insurance subject for his master's thesis. Finally, my very special friend, Jan Scott, helped immeasurably by proofreading and retyping some of the text and by suggesting sharper prose where too often confusion lurked. Any errors of fact, omission, or interpretation contained herein remain, of course, my sole responsibility.