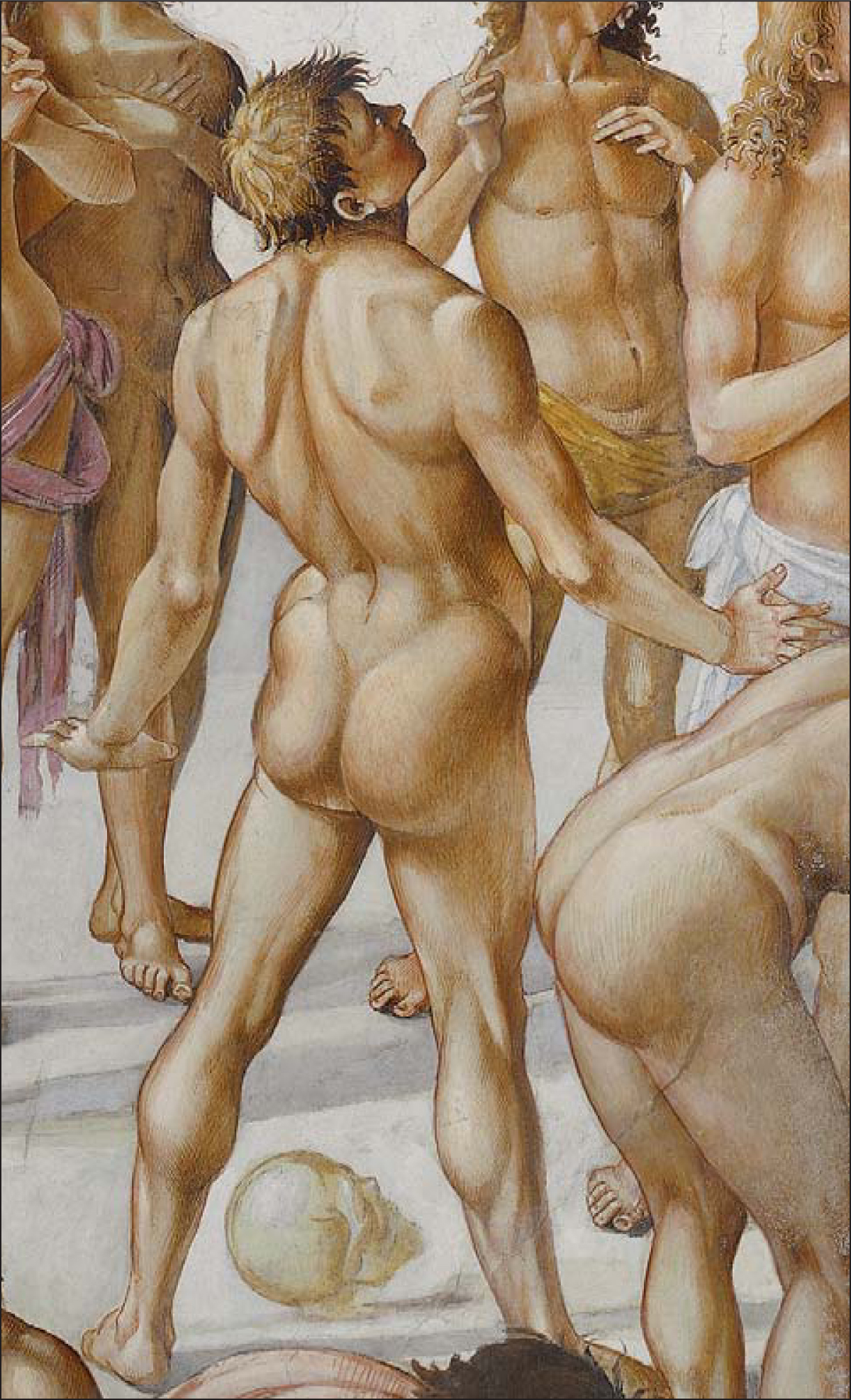

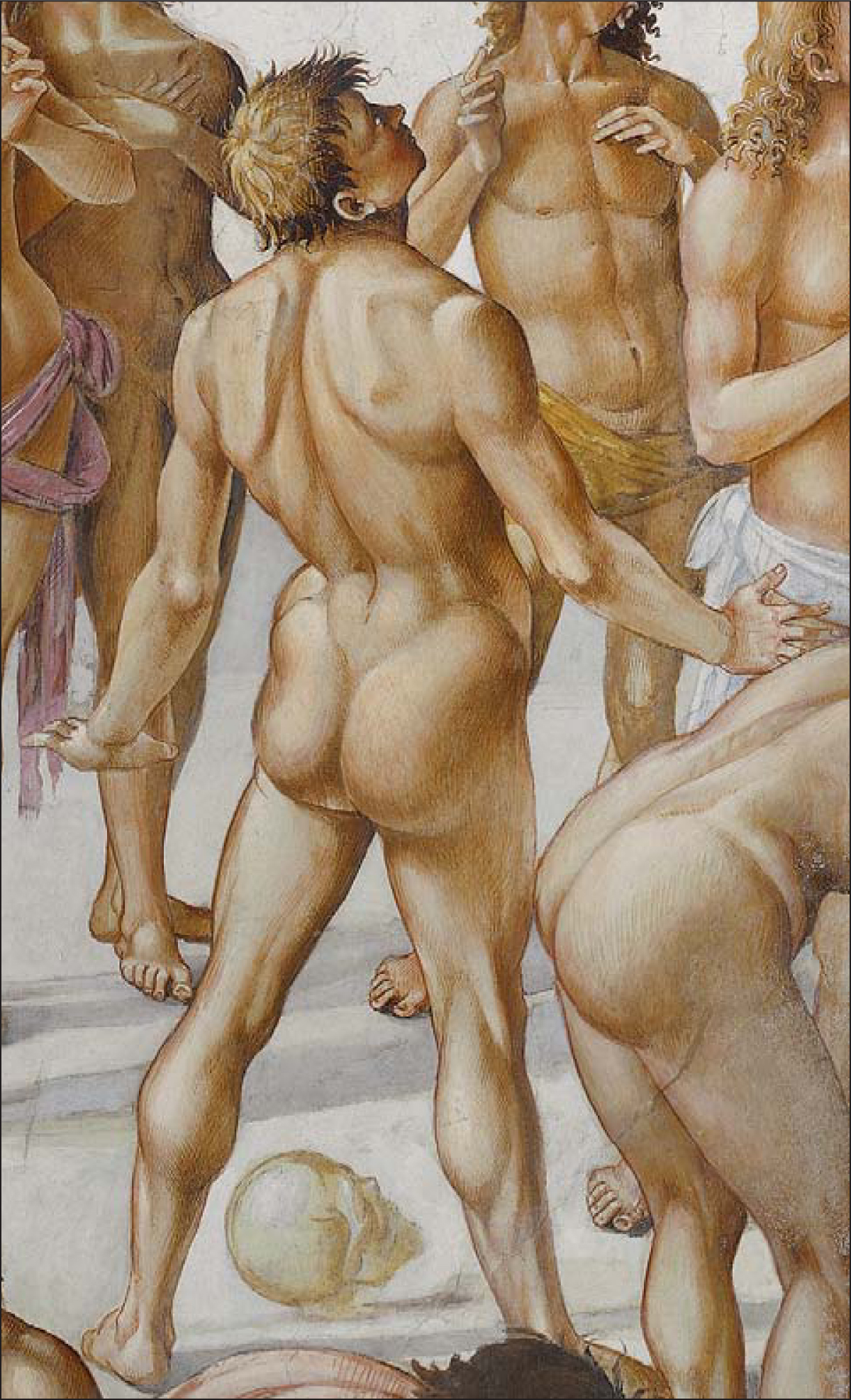

Plate 1. Detail of The Resurrection of the Flesh

First published in the United States in 2017 by

Bellevue Literary Press, New York

For information, contact:

Bellevue Literary Press

NYU School of Medicine

550 First Avenue

OBV A612

New York, NY 10016

2017 by Nicholas Fox Weber

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the publisher upon request

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a print, online, or broadcast review.

Bellevue Literary Press would like to thank all its generous donorsindividuals and foundationsfor their support.

With thanks to the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation for their support of this book

This publication is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.

This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Book design and composition by Mulberry Tree Press, Inc.

First Edition

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

ebook ISBN: 978-1-942658-27-6

For Lucy

AUTHORS NOTE

Unless otherwise stated, all the illustrations in this book are from The Last Judgment, the fresco cycle painted by Luca Signorelli in the Cappella Nova of the cathedral in Orvieto between 1499 and 1504. Other works by Signorelli are identified by title only.

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

I N SEPTEMBER OF 1897, the forty-one-year-old Sigmund Freud set out for central Italy. A high point of the trip for the Viennese neurologist, who was then fine-tuning the process he called psychoanalysis, was his encounter with a fresco cycle by the Renaissance master Luca Signorelli in the cathedral at Orvieto. This brilliantly colored group of pictures packed into a small side chapel is a vivid depiction of muscular nude men. Depending on the destiny meted out to them in the Last Judgment, most of these burly specimens of raw masculine power are consigned to forms of damnation rendered in horrific detail, while a few ascend to a heavenly bliss. With their ripped torsos and gladiators limbs, they go to the limits of their physical force. Many of them are engaged in furious battle. They inflict torture brutally or muster supernatural strength to defend themselves against it. The selected elite have no such struggles as they celebrate their reward for an admirable past, but we hardly notice them in their boring calm.

A year after the visit to Orvieto, Freud started to talk to a traveling companion about these early-sixteenth-century paintings that had moved him deeply. Some sourcesand there are numerous accounts of the events that followedsay that the conversation occurred on a train Freud was taking on a trip into Herzegovina, having left behind his sick wife. But in his own version of the facts, which Freud wrote less than a week after the journey when he enthused about the frescoes, he reports that he was on a carriage drive from Ragusa (now Dubrovnik, on the Dalmatian coast of the Adriatic) into a nearby village in Herzegovina for an idyllic outing during a late-summer holiday. The person with whom he was speaking was, depending on the source, either a complete stranger or a Berlin lawyer, Herr Freyhau, whom Freud apparently already knew.

For all the discrepancies of details, the main event that concerns us is always recounted in the same way. It is that, to his immense frustration, Freud could not recall the name of the artist. Following the journey, he wrote his friend Wilhelm Fliess, I could not find the name of the renowned painter who did the Last Judgment in Orvieto, the greatest I have seen so far. For at least two days (the duration varies according to the source; again we are in murky territory), Freud sustained the memory loss, and was reduced to inner tormenthis wordsas he repeatedly tried but failed to conjure the artists name.

To his amazement, Freud could, nonetheless, see certain details of the fresco cycle perfectly in his minds eye. Then, once he was reminded that the person who had made these powerful paintings had the last name of Signorelli, he recalled that the first name was Luca, and instantly lost his ability to envision the art.

Freud at the time was embarking on his self-analysis. Using elements of the technique that Anna Othe pseudonym of a patient of his colleague Josef Breuercalled the talking cure, he was hoping to treat his own psychosomatic disorders as well as exaggerated fears of dying and other phobias by investigating his dreams and memories. What he could not remember intrigued him even more. He was startled by his inability to recall the name of an artist he felt he should have easily recalled, and considered his incapacity revelatory.

Freud became determined to understand his own mental process generated by the discussion he had been having that prompted him to envision the paintings at Orvieto and then to bury the name Signorelli. He wrote Fliess, In the conversation, which aroused memories that evidently caused the repression, we talked about death and sexuality.... How can I make this credible to anyone? It was as if he believed that the subject matter of the conversation had caused him to block out the name, and his greatest task was to have others recognize that link. I believe that Freud, focusing only on the need to convince others of general mental processes, was managing to avoid personal truths that made him unbearably uncomfortable. The folderol about the impossibility of bringing the name Signorelli to the conscious part of his mind was like the parapraxis itself: an obfuscation. By that I do not mean a deliberate deception. I mean that Uncle Siggy, like the rest of us, just could not always cope with the complexity of being human.

FIVE DAYS AFTER DESCRIBING THIS MEMORY LOSS, Freud wrote Fliess again to say that he had completed an essay on the phenomenon of forgetfulness, which he had sent to a medical journal. He began that early short text on the mysterious workings of the human mind almost as if he were writing a folktale: In the middle of carrying on a conversation we find ourselves obliged to confess to the person we are talking to that we cannot hit on a name we wanted to mention at that moment, and we are forced to ask for hisusually ineffectualhelp. What