Totem and Taboo

Freud has told us that for him all natural science, medicine, and psychotherapy were a lifelong journey round and back to the early passion of his youth for the history of mankind, for the origins of religion and morality an interest which at the height of his career broke out to such magnificent effect in Totem and Taboo .

Thomas Mann

Relations between social anthropology and psychology are still ill-defined and unstable. But in any resolution of them the work of psychoanalysts must be taken very seriously into account. It is very useful, then, to have this new translation of the pioneer work.

Nature

Freud had a strong element of the artist in his composition. Nearly all his work was well translated into English, with one glaring exception: Totem and Taboo . Now, at last ... justice has been done.... The book itself is one of the most fascinating and characteristic, and also of the most speculative, in the whole Freudian canon.

Books of the Month

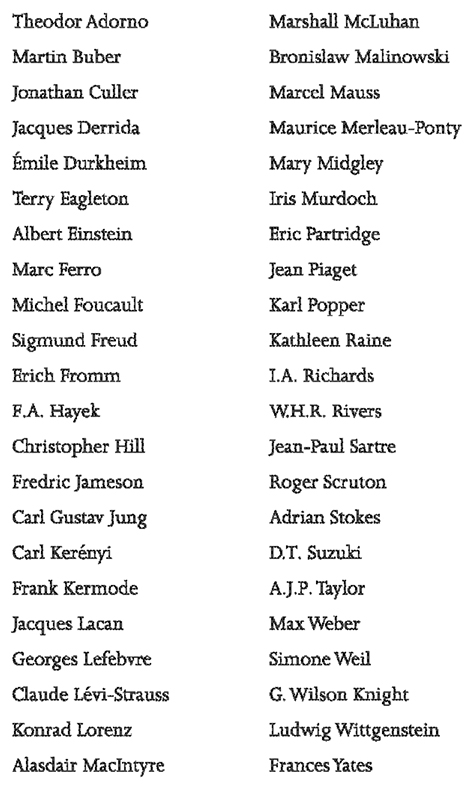

Routledge Classics includes

For a complete list of titles visit WWW.roufledgeclassics.com

Sigmund

Freud

Totem and Taboo

Some Points of Agreement between the

Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics

Authorized translation by James Strachey

First published 1913 by Hugo Heller

English edition first published in the United Kingdom 1919

by George Routledge & Sons

This translation first published 1950 by Routledge & Kegan Paul

First published in Routledge Classics 2001

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Translation 1950 Routledge & Kegan Paul

Typeset in Joanna by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN10: 041525387X

ISBN13: 9780415253871

Contents

As Freud explains in his own preface, the four essays comprised in this volume were originally published in the pages of the periodical Imago (Vienna) under the title ber einige bereinstimmungen im Seelenleben der Wilden und der Neurotiker [On Some Points of Agreement between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics]the first and second essays in Vol. I (1912) and the third and fourth in Vol. II (1913). All four essays were collected and published under the new title of Totem und Tabu in 1913 (Vienna, Hugo Heller). New editions appeared in 1920, 1922 and 1934 and the work was included in Volume X of Freuds Gesammelte Schriften (Vienna, 1924) and as Volume IX of his Gesammelte Werke (London, 1940). None of these later editions show any variations of substance from the original one. An English translation by A. A. Brill was published in New York in 1918 (London, 1919). The book has also been translated into Hungarian (1918), Spanish (1923), Portuguese ( n.d. ), French (1924), Japanese (twice, 1930 and 1934) and Hebrew (1939). The last of these was introduced by a specially written preface, which, on account of its particular interest, I have included in this volume.

For the purposes of the present, entirely new, version I have made an effort to verify all quotations and references so far as possible; and I have put right a considerable number of inaccuracies which had crept into the German editions. Particulars of all works referred to in the text will be found in a list at the end of the volume. The responsibility for any matter printed between square brackets is mine.

My grateful thanks are due to Miss Anna Freud for her critical revision of the entire translation, and to Mr. Roger Money-Kyrle for reading through the typescript and making many helpful suggestions.

J. S.

The four essays that follow were originally published (under a heading which serves as the present books sub-title) in the first two volumes of Imago , a periodical issued under my direction. They represent a first attempt on my part at applying the point of view and the findings of psycho-analysis to some unsolved problems of social psychology [ Vlkerpsychologie ]. Thus they offer a methodological contrast on the one hand to Wilhelm Wundts extensive work, which applies the hypotheses and working methods of non -analytic psychology to the same purposes, and on the other hand to the writings of the Zurich school of psycho-analysis, which endeavour, on the contrary, to solve the problems of individual psychology with the help of material derived from social psychology. (Cf. Jung, 1912 and 1913.) I readily confess that it was from these two sources that I received the first stimulus for my own essays.

I am fully conscious of the deficiencies of these studies. I need not mention those which are necessarily characteristic of pioneering work; but others require a word of explanation. The four essays collected in these pages aim at arousing the interest of a fairly wide circle of educated readers, but they cannot in fact be understood and appreciated except by those few who are no longer strangers to the essential nature of psycho-analysis. They seek to bridge the gap between students of such subjects as social anthropology, philology and folklore on the one hand, and psycho-analysts on the other. Yet they cannot offer to either side what each lacksto the former an adequate initiation into the new psychological technique or to the latter a sufficient grasp of the material that awaits treatment. They must therefore rest content with attracting the attention of the two parties and with encouraging a belief that occasional co-operation between them could not fail to be of benefit to research.

It will be found that the two principal themes from which the title of this little book is derivedtotems and tabooshave not received the same treatment. The analysis of taboos is put forward as an assured and exhaustive attempt at the solution of the problem. The investigation of totemism does no more than declare that here is what psycho-analysis can at the moment contribute towards elucidating the problem of the totem. The difference is related to the fact that taboos still exist among us. Though expressed in a negative form and directed towards another subject-matter, they do not differ in their psychological nature from Kants categorical imperative, which operates in a compulsive fashion and rejects any conscious motives. Totemism, on the contrary, is something alien to our contemporary feelingsa religio-social institution which has been long abandoned as an actuality and replaced by newer forms. It has left only the slightest traces behind it in the religions, manners and customs of the civilized peoples of to-day and has been subject to far-reaching modifications even among the races over which it still holds sway. The social and technical advances in human history have affected taboos far less than the totem.