The Black Cultural Front

The Black Cultural Front

Black Writers and Artists of the Depression Generation

Brian Dolinar

Margaret Walker Alexander Series in African American Studies

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Copyright 2012 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2012

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dolinar, Brian.

The black cultural front : black writers and artists of the depression generation / Brian Dolinar.

p. cm. (Margaret Walker Alexander series in African American studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61703-269-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-61703-270-7 (ebook) 1. American literatureAfrican American authorsHistory and criticism. 2. American literature20th centuryHistory and criticism. 3. African AmericansIntellectual life. I. Title.

PS153.N5D595 2012

810.9896073dc23 2011040426

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

To James H. Thomas

Contents

CHAPTER 1

The National Negro Congress and the Radical Roots of the Black Cultural Front

CHAPTER 2

When a Man Sees Red

Langston Hughes and the Simple Stories

CHAPTER 3

A Writer of Revolutionary Potential

Chester Himes and Black Noir

CHAPTER 4

Battling Fascism for Years with the Might of His Pen

Ollie Harrington and the Bootsie Cartoons

Keeping the Memory of Survival Alive

Acknowledgments

A student is only as good as his teacher, and I have been fortunate to have many generous teachers. James H. Thomas, professor in American Studies at Wichita State University, was my first mentor, and he gave me the inspiration to become a writer and educator. Ranu Samantrai, then a Cultural Studies professor at Claremont Graduate University in Los Angeles, first suggested I write a book on the black cultural front. In the early stages of this project, Val Thomas, professor in African American literature at Pomona College, was a helpful sounding board and provided much-needed direction. I also benefited greatly from the tutelage of Sid Lemelle and Phyllis Jackson, professors in Black Studies.

Since moving to Urbana-Champaign in 2004, I have received what has been a second education both from those at the University of Illinois, as well individuals in the larger community. There have been a number of scholars working on the long history of African American radicalism including Erik McDuffie, Clarence Lang, Fanon Che Wilkins, and William Maxwell, all of whom freely shared their knowledge with me. Additionally, I received guidance from Jim Barrett, David Roediger, and Lou Turner. Belden Fields and Antonia Darder provided me with two shining examples of scholar-activists who were involved in the community and brought with them the rigor of their academic backgrounds. From other community membersCarol and Aaron Ammons, Danielle Chynoweth, Barbara Kessel, Durl Kruse, Martel Miller, Patrick ThompsonI learned directly about grassroots political organizing that has been useful in writing about the history of the American Left. Additionally, I have cherished my friendship with Gregory Koger, who constantly reminds me of the need for revolutionary change.

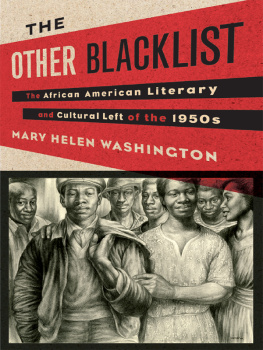

I have been lucky to have several fellow scholars of the American Left offer their encouragement. In particular, Alan Wald has been tremendously generous in sharing his encyclopedic knowledge of American literary and cultural radicalism. I am thankful to Barbara Foley for our several engaging conversations and her insightful criticism. In the final stages of my project, Mary Helen Washington helped me to more clearly comprehend the vision that the Communist Party provided to African American artists and writers.

One of the most memorable aspects of this project has been meeting the fascinating people who gave me further insight into the lives of Langston Hughes, Chester Himes, and Ollie Harrington, as well as the context of the Depression. Biographer Edward Margolies invited me to his New York apartment for a conversation about Chester Himes. Roger Jelliffe allowed me to interview him about his parents, the founders of the Karamu House. I also spoke with Reuben and Dorothy Silver, who recalled their days at Karamu and memory of Langston Hughess time there. I was fortunate to have a phone conversation with Constance Webb Pearlstein before she passed away about her friendship with Chester Himes. Christine McKay, a researcher of the Schomburg Center, openly shared with me her biographical research on Ollie Harrington. I am also grateful to Helma Harrington for reading my chapter on her husband and talking with me on the phone from her home in Berlin.

Lastly, my deepest appreciation is for my partner Sarah, who has been my toughest critic and my most ardent supporter.

The Black Cultural Front

Introduction

In a cultural session at the 1940 conference of the National Negro Congress (NNC), several people talked of the need to build a cultural front. On the panel was Gwendolyn Bennett, African American poet and educator, who proposed that the NNC spend more time, space, and effort on the cultural front. A woman in the audience listed only as Mrs. Lynch spoke up to insist that the work of the cultural group was essential because it is the cultural things that keep us from going stark crazy. The Black Cultural Front will explain how African American writers and artists were swept up in the political struggles of the 1930s and beyond. They often participated directly in these events, but their greatest contribution was through their art. Ultimately, this study will be interested in the aesthetic responses they produced that spoke to the times in powerful and imaginative ways. By dramatizing the issues of their day, they helped themselves and others to keep from going stark crazy as mass joblessness gripped the country, Jim Crow dominated the South, and fascism spread throughout Europe.

The common understanding has been that the Communist Party hindered black cultural expression during this period. As I will show, the Communist-led Left promoted several cultural organizations to draw black cultural workers into its orbit. Most important was the National Negro Congress to which numerous black artists and writers contributed their talents. The NNC was a coalition of civil rights groups and labor organizations officially launched in 1936 at a national conference in Chicago. Its formation was typical of Popular Front organizing, a time when the Communist Party softened its revolutionary rhetoric to work with liberal groups. The NNC reached out to the newly formed Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which heavily recruited African Americans into the labor movement. With the appointment of A. Philip Randolph as its president, the NNC also courted the AFL-affiliated Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. In addition to bringing black workers into the labor movement, NNC organizers also worked on the cultural front by convening panels with artists and writers at its conferences, organizing campaigns against discrimination in Hollywood, and

The story of African American writers and artists who took a sincere interest in the American Left has yet to be fully appreciated. Since the mid-1940s, accounts of betrayal by black ex-Communists have come to represent a mass defection of African Americans from the Communist Party. In Richard Wrights tell-all expos I Tried to Be a Communist, appearing in two installments of the

Next page