THE LETTERS OF KINGSLEY AMIS

EDITED BY

Zachary Leader

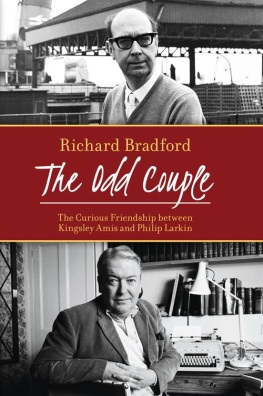

Throughout his life, in addition to writing poems, novels, short stories, essays, critical studies, radio and television adaptations and programmes, reviews, and editing anthologies, Kingsley Amis was a prolific and inventive letter-writer. He was fully aware of the value of his correspondence. What a feast is awaiting chaps when were both dead and our complete letters come out, he writes to Philip Larkin on 24 September 1956, after a sodding good day reading over Larkins letters to him. When in 1955 an attack on Laurie Lee in the Spectator generates a heated correspondence, Amis imagines its likely afterlife in a letter of 22 August to Robert Conquest: Its nice to think that our exchange of views on the Laurie question will almost certainly appear, say about 1990 you know, a book of about 50pp. costing 8/6: Spanish Fly a literary exchange: the Amis-Conquest correspondence edited by John Wain, O. M., published by Hartley and Tomlinson. Several letters reflect on the proper idiom or style for the correspondence. I think your letters are very good, too, he writes to Larkin on 22 April 1947. I see what you mean about formality and content; I think so too sometimes, but I enjoy the capital-&-underlining stuff so much. I think whag ramsh what you say apl lambsh applies chiefly to descriptions and scenarios.

Ramsh and lambsh here (one begetting the other, as it were) catch whag and apl (typos for what and applies) and are just the sort of intricate foolery Amis enjoys. The correspondence with friends is meant to entertain, and is sometimes worked at with fanatical ingenuity, even when its subjects are boredom or business. I wrote you a letter a couple of days ago, he writes to Larkin on 18 September 1979, but tore it up because when I read it through it turned out to be full of whining self-pity. I mean nothing wrong with self-pity but I dont want you thinking when a letter arrives Oh fuck whatll he be on about this time. (What Larkin in fact thought was just the opposite: The obsessively-neatly typed address and Hampstead postmark sets me chuckling in advance, he declares in a letter of 16 January 1981.) Self-pity in this instance derives in part from the tedium of more routine correspondence:

Ive just written a lot of turdy letters to strangers. Do you get that much? Find yourself writing things like unable to accept your kind invitation to address the Literary Soc any merit. However this is only one mans opinion and your poems give up all debating, especially on facetious motions. I hope you away from my typewriter. So I will just wish the festival all the charity already and feel I should not spread myself too thin, or secretary recently and can only assume the previous one failed to sorry about the delay which was due to please accept my apologies. No I wouldnt mind if they all stopped writing.

Even the sorts of letters Amis is parodying here, though, have their moments, as when he informs the Secretary of the Eton Literary Society, in a letter of 30 December 1970, that if I ever (these days) gave a talk anywhere, it would be at Eton, what with it being such a haunt of the Establishment and the ruling class and all, or when he accepts a minuscule rights fee on the grounds that even chickenfeed has some nourishment value (in a letter to Liz Calder, Publicity Manager at Gollancz, 1 MAY 1974). Amis, I am arguing, took his duties as a correspondent seriously (once he got around to them), especially when least serious, often when the duties themselves were most mundane. The letters matter, as a result, because they are so good, the best of them as funny and perceptive as anything he ever wrote.

They also matter because they tell us much about the man and his work: as novelist, poet, critic, anthologist, polemicist and teacher. From the start Amis was a figure of controversy: at the heart of the pre-eminent poetical grouping of post-war Britain, the Movement; the earliest of redbrick novelists and Angry Young Men. These labels he mostly resisted, but he did so in letters that reveal much about their origin and meaning. Politically, he was also high-profile (a phrase he wouldnt much like): an outspoken Communist at Oxford in the early 1940s; a vocal opponent of capital punishment in the 1950s; a defender of United States policy in Vietnam in the 1960s; an arch-conservative (anti-Soviet, anti-educational reform, anti-Common Market, anti-government subsidy) from the mid-1960s onwards. The private letters are often more nuanced and tentative also cruder about social and political issues than are the public letters, products of what he calls, in a letter to Larkin of 9 November 1952, the awful neurotic write to the papers fit. They also show him as an enthusiastic, if intermittent, conspirator and campaigner, eager to orchestrate and sway public debate.

But the writing of novels and poems, that is always comes first. Work holds up my letter writing, speeds yours, Amis explains to Conquest in a letter of 13 December 1977. Unlike you, he writes on 3 July 1978, after another lengthy silence, I shy away from personal letters till my desk is clear. When caught up in work, or late with it, Amis simply ignored correspondence, and most everything else. Hes so exhausted at the moment with over work that as you see he cant even put pen to paper, apologises his first wife, Hilly, in an undated letter of 1962 to Edmund and Mary Keeley (now among Edmund Keeleys papers in the Princeton Library). As she explains later in the letter:

he really does mean to do these things but is so shagged to buggery. I spend all my time ringing up people [] the day after we should have been there trying to explain the whole thing laughing (up your bum) away & isnt it cute that K never gets round to answering invitations & doesnt even discover them till 24 hours after the event was supposed to take place, & I cant spell or write, but so lucky I can count & phone up sometimes, pretty soon no one will ask us any more & our problems will be over.

In a number of letters, mostly to Larkin or sympathetic researchers, the work itself takes centre stage. Early in their friendship Amis and Larkin read each others unpublished poems, novels and stories, offering detailed suggestions and criticisms. They also collaborated on poems and stories in the 1940s and later (see, for example, the Ron Cain parodies in Appendix B, printed here for the first time). In several letters, Amis calls on friends or family for background information. As regards the literary mission youve kindly said youd do for me, he writes in a letter of 20 June 1962 to William Rukeyser, an ex-student from Princeton, this is what I would ideally like (he is at work on One Fat Englishman, set in the United States):

What my hero Roger Micheldene would notice in Greenwich-Village-type-surroundings at night both in the street and in a bar or two and in the morning.

Short description of modest but not squalid apartment in the nearby area.

Anything at all about $50,000-a-year house and grounds located anywhere between 30 and 60 miles from Manhattan, out in the country rather than in small town, though either would do []

As an Englishman Roger would have his eye and ear open for oddities, but as you know for the authors benefit nothing is more helpful than simple details of lay-out of rooms, size of hallways etc., such as will help the author to visualise the thing in general terms.

A similar request to Martin Amis (while the father was at work on Girl, 20 (1971), and before the son had published anything) results in a detailed description of a London discotheque. The son knows exactly what the father needs: