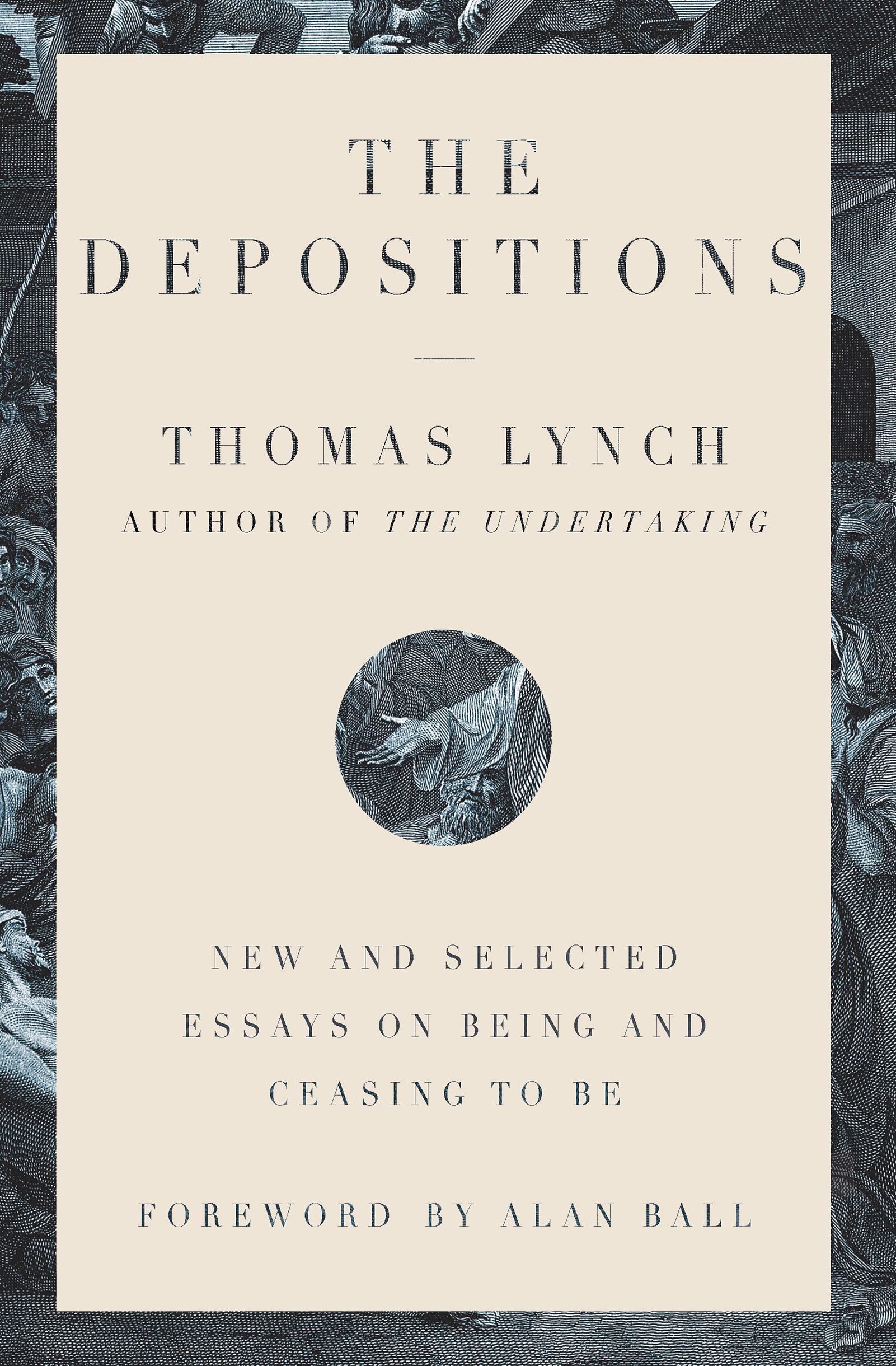

THE

DEPOSITIONS

NEW AND SELECTED

ESSAYS ON BEING AND

CEASING TO BE

THOMAS LYNCH

FOREWORD BY ALAN BALL

W.W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

W hen I was thirteen, my older sister was killed in a car accident. She was driving me to a piano lesson, and at a blind intersection she pulled out in front of a speeding car which slammed into the drivers door of our 1970 Ford Pinto. She was killed instantly. I emerged without a scratch. Well, physically.

On that day life irrevocably changed for me, split into Before and After. Now I knew. Death exists. It happens. Like many people, I would spend the next many years doing whatever the hell I could to distract myself from that inconvenient truth.

Almost thirty years later, HBO executive Carolyn Strauss pitched me the idea of a television show set in a family-run funeral home. I remembered time I had spent in funeral homes growing upfor my sister, a grandfather, a great-aunt, a grandmother, and finally my dadand the sticky, surreal dreamlike feel of those times, and something in my head just said yes.

Carolyn had mentioned a book called The American Way of Death by Jessica Mitford she had read, so I bought a copy to do my writerly research. It turned out to be a kind of screed against the funeral industryor, as it prefers to be known, the Death Care Industry. Mitford seemed shocked by the mechanics of embalming bodies and offended by the fact that services and products were actually marked up for profit. But she saved her greatest ire, her most righteous indignation, for the idea of salesmen selling to people in their most vulnerable moments, when they might equate the amount of money spent on a casket with the amount of love felt for the person in that casket. As if every other industry in the world would not want an advantage like that.

I knew I didnt want to create a show about guys in suits guilting grieving widows out of a few extra dollars. I thought back to the time I had spent in funeral homes and realized I couldnt even remember the presence of funeral directors, they were so silent and unobtrusive. Except for the time my mother broke down at my sisters open casket, and a kindly unthreatening man glided in from nowhere and took her behind a curtain to give her privacy.

I still didnt know how to tell the story of the people we pay to face death for us. And then I discovered Thomas Lynch and his lovely, profound work.

I think a lot of people, maybe most people, who have been touched by death live either in existential terror of it or in complete denial that death happens. Thomas Lynch walks a razor-thin edge in between those polarities. He cannot deny death, he sees it every day, he works with it, he holds it in his hands. Nor is he terrified by something so ubiquitous, by something that is such a fundamental part of life.

Reading Thomass work is to suddenly be able to see what its like to be comfortable with mortality. To respect it but not fear it. To see both the absurdity and the beauty of death, sometimes simultaneously. To know that living in the constant presence of death (which we all do, whether we admit it or not) is most importantly living, facing and navigating the harsh truths and the unexpected joys, the grief and the gratitude, all with an unblinking humorous and poetic eye.

I will always be grateful to Thomas for his wit and generosity and his gorgeous writing, for helping me see what the soul of Six Feet Under could be, and for helping me grow a little in my own complicated and omnipresent awareness of mortality. For reminding me again and again of the immutable truth of life and death and the necessity of being able to shrug it off while still staring it straight in the face. What else are you going to do? Life goes on.

Until it doesnt.

ALAN BALL

Life Studies from the Dismal Trade

E very year I bury a couple hundred of my townspeople. Another two or three dozen I take to the crematory to be burned. I sell caskets, burial vaults, and urns for the ashes. I have a sideline in headstones and monuments. I do flowers on commission.

Apart from the tangibles, I sell the use of my building: eleven thousand square feet, furnished and fixtured with an abundance of pastel and chair rail and crown moldings. The whole lash-up is mortgaged and remortgaged well into the next century. My rolling stock includes a hearse, two Fleetwoods, and a minivan with darkened windows our pricelist calls a service vehicle and everyone in town calls the Dead Wagon.

I used to use the unit pricing methodthe old package deal. It meant that you had only one number to look at. It was a large number. Now everything is itemized. Its the law. So now there is a long list of items and numbers and italicized disclaimers, something like a menu or the Sears Roebuck Wish Book, and sometimes the federally-mandated options begin to look like cruise control or rear-window defrost. I wear black most of the time, to keep folks in mind of the fact were not talking Buicks here. At the bottom of the list there is still a large number.

In a good year the gross is close to a million, five percent of which we hope to call profit. I am the only undertaker in this town. I have a corner on the market.

The market, such as it is, is figured on what is called the crude death ratethe number of deaths every year out of every thousand persons.

Here is how it works.

Imagine a large room into which you coax one thousand people. You slam the doors in January, leaving them plenty of food and drink, color TVs, magazines, and condoms. Your sample should have an age distribution heavy on baby boomers and their children1.2 children per boomer. Every seventh adult is an old-timer, who, if he or she wasnt in this big room, would probably be in Florida or Arizona or a nursing home. You get the idea. The group will include fifteen lawyers, one faith healer, three dozen real-estate agents, a video technician, several licensed counselors, and a Tupperware distributor. The rest will be between jobs, middle managers, neer-do-wells, or retired.

Now for the magic partcome late December when you throw open the doors, only 991.6, give or take, will shuffle out upright. Two hundred and sixty will now be selling Tupperware. The other 8.4 have become the crude death rate.

Heres another stat.

Of the 8.4 corpses, two-thirds will have been old-timers, five percent will be children, and the rest (slightly less than 2.5 corpses) will be boomersrealtors and attorneys likelyone of whom was, no doubt, elected to public office during the year. Whats more, three will have died of cerebral-vascular or coronary difficulties, two of cancer, one each of vehicular mayhem, diabetes, and domestic violence. The spare change will be by act of God or suicidemost likely the faith healer.

The figure most often and most conspicuously missing from the insurance charts and demographics is the one I call The Big One, which refers to the number of people out of every hundred born who will die. Over the long haul, The Big One hovers right around... well, dead nuts on one hundred percent. If this were on the charts, theyd call it

Next page