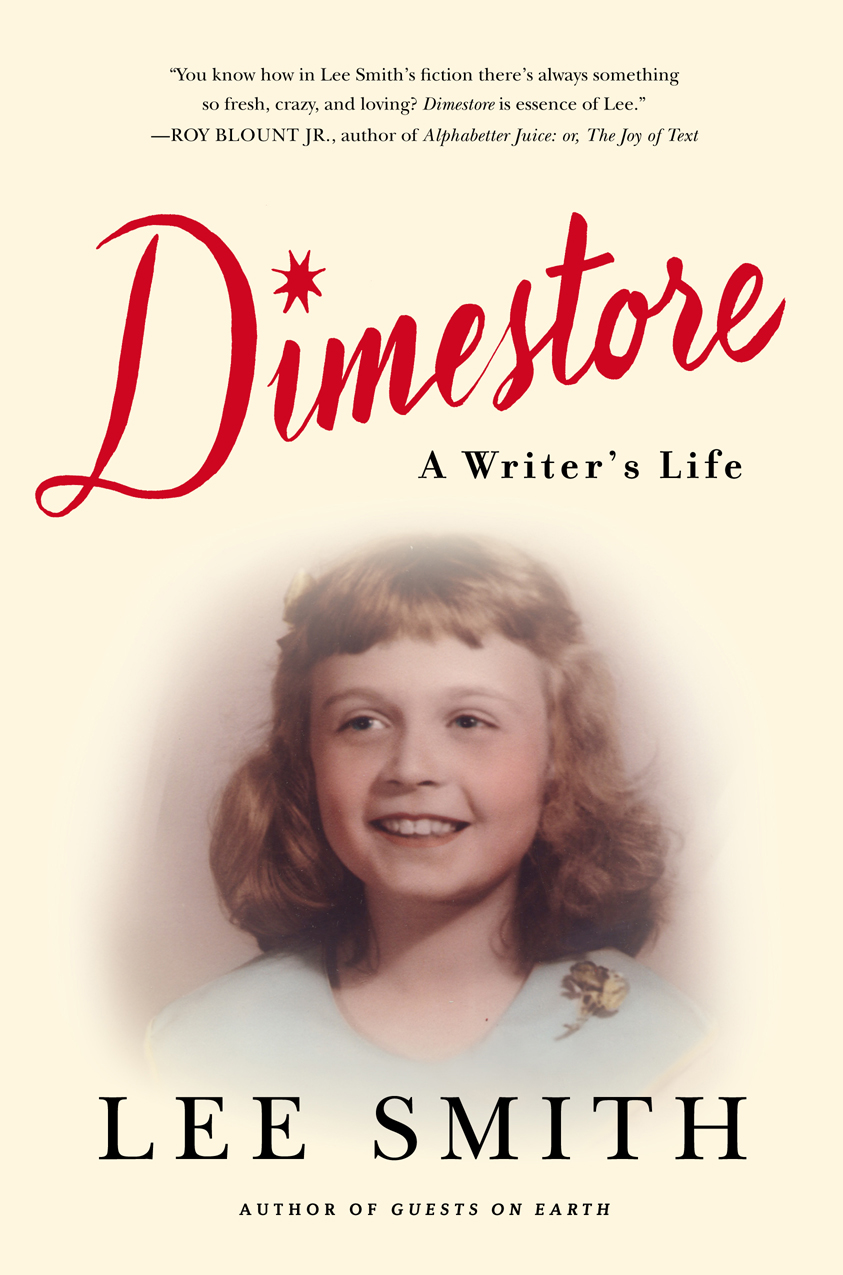

DIMESTORE

LEE SMITH

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL 2016

Also by Lee Smith

NOVELS

The Last Day the Dogbushes Bloomed

Something in the Wind

Fancy Strut

Black Mountain Breakdown

Oral History

Family Linen

Fair and Tender Ladies

The Devils Dream

Saving Grace

The Christmas Letters

The Last Girls

On Agate Hill

Guests on Earth

STORY COLLECTIONS

Cakewalk

Me and My Baby View the Eclipse

News of the Spirit

Mrs. Darcy and the Blue-Eyed Stranger

NONFICTION, EDITED WITH INTRODUCTION

Sitting on the Courthouse Bench

An Oral History of Grundy, Virginia

For my grandchildren,

Lucy, Spencer, Ellery, and Baker

Writing fiction has developed in me an abiding respect for the unknown in a human lifetime and a sense of where to look for the threads, how to follow, how to connect, find in the thick of the tangle what clear line persists. The strands are all there: to the memory nothing is ever really lost.

The events in our lives happen in a sequence in time, but in their significance to ourselves they find their own order, a timetable not necessarilyperhaps not possiblychronological. The time as we know it subjectively is often the chronology that stories and novels follow: it is the continuous thread of revelation.

One Writers Beginnings, Eudora Welty

Contents

PREFACE

Raised to Leave: Some Thoughts on Culture

I WAS BORN IN A RUGGED RING of mountains in southwest Virginiamountains so high, so straight up and down, that the sun didnt even hit our yard until about eleven oclock. My uncle Bob Venablethey lived across the roadused to predict the weather by sticking his head out the window and hollering back inside, Sun on the mountaintop, girls! to my cousins. The only flat land in the county lay in a narrow band along the river where we lived, about a mile from town. Though we all ate out of the garden, real farming was impossible in that hard rock ground. The only thing it produced was coal. We never thought of our jagged mountains as scenic, either, though we all played up in them every day after school. We never saw a tourist, and nobody we knew hiked for fun.

I will never forget the first time I ever saw a jogger: my mother and I were sitting on the front porch stringing beans and watching the cars go up and down Route 460 in front of our house, when suddenly one of these VISTAs wed been hearing about, a long-haired boy with great legs, came running right up the road. We both stood up, and watched him run out of sight. Well, for heavens sakes, my mother said. Where do you reckon hes going, running like that?

He was going back to where he came from, eventually; but most of us werent going anyplace. We were closed in entirely, cut off from the outside world by our ring of mountains. Many of the children I went to school with had never been out of Buchanan County. People still described my own mother as not from around here, though she had spent most of her life teaching their children and trying to civilize you and your daddy! as she always joked, but it was a challenge.

So I was being raised to leave.

I WAS NOT TO USE double negatives; I was not to say me and Martha. I was not to trade my pimento cheese sandwiches at school for the lunch I really wanted: cornbread and buttermilk in a mason jar, brought by the kids from the hollers. Me and Martha were not to play in the black river behind our house, dirty with coal that would stain my shorts. I was to take piano lessons from the terrifying Mrs. Ruth Boyd even though I had no aptitude for it. I was to play Clair de Lune at my piano recital, wearing an itchy pink net evening dress.

I was not to like the mountain music that surrounded us on every side, from the men playing banjo and mandolin on the sidewalk outside my daddys dimestore on Saturdays, to Marthas father playing his guitar down on the riverbank after dinner, to Kitty Wells singing It Wasnt God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels on our brand-new radio station, WNRG. But here, my mother ran into serious trouble. For I loved this music. I had been born again to Angel Band, sung high and sweet at a tent revival that I had to sneak out to go to; and I had a dobro-playing boyfriend, with Nashville aspirations.

Even my mother enjoyed going to the drive-in theater on Saturday evenings in the summer to hear two brothers from over in Dickenson County, Ralph and Carter Stanley, play and sing their bluegrass music on top of the concrete-block concessions stand. I never will marry, Ill take me no wife; I intend to live single, all of my life, Ralph wailed mournfully, followed by their fast instrumental version of Shout, Little Lulie. Old people were clogging on the patch of concrete in front of the window where you bought your Cokes and popcorn; little kids were swinging on the iron-pipe swing set. Whole families ate fried chicken and deviled eggs theyd brought from home, sitting on quilts on the grass. My boyfriend reached over and squeezed my sweaty hand. The Stanley Brothers nasal voices rose higher than the gathering mist, higher than the lightning bugs that rose from the trees along the river as night came on. When it got full dark, the Stanley Brothers climbed down off the concession stand and we all got into our cars and the movie came on.

I loved that music, just as I loved my grandmothers corn pudding and those scary old stories my Uncle Vern told. But this hillbilly music didnt have anything to do with culture, as I was constantly being reminded. No, culture was someplace else, and when the time came, I would be sent off to get some. Culture lived in big cities like Richmond, and Washington, and Boston and New Yorkespecially in New York, especially in places like Carnegie Hall.

Forty years later, I stood on my hundred-dollar balcony seat in Carnegie Hall and screamed as seventy-four-year-old Dr. Ralph Stanley and the rest of the traditional musicians and singers from the phenomenally successful O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack played to a sold-out house. Elvis Costello was the emcee; Joel and Ethan Coen, the filmmakers who made the O Brother movie, were in the audience, along with T Bone Burnett, its musical director. The Coen Brothers had written this note about the music in the program, aimed at their New York audience: These songs were for the most part created by people whose lives were hard and horizons narrow. Their lives were not like ours. All that urges their music on us is its humanity... And yet, this soundtrack went platinum without receiving any airplay: pop stations considered it too country, and country stations considered it too... country.

On stage at Carnegie Hall, the Fairfield Four sang their stark treatment of Po Lazarus. Dan Tyminski tore it up on I Am a Man of Constant Sorrow. The Cox family, fresh from Louisiana, brought down the house with Will There Be Any Stars in My Crown. Reigning bluegrass princess Alison Krauss fiddled up a storm, then sang When I Go Down to the River to Pray in tight harmony with Gillian Welch and Emmylou Harris. They sang so sweet, they could have been angels. The little Peasall sistersSarah, age thirteen, Hannah, age ten, and Leah, age eight, wore patent-leather shoes and bows in their hair to sing In the Highways and the Hedges, Ill Be Somewhere Listening for My Name. Gillians husband, David Rawlings, teamed up with her on I Want To Sing That Rock and Roll.