Copyright 2015 David Cooper

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Typeset in Minion Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by Gomer Press Ltd, Llandysul Enterprise Park, Llandysul, Ceredigion, SA44 4JL

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cooper, David, 1956

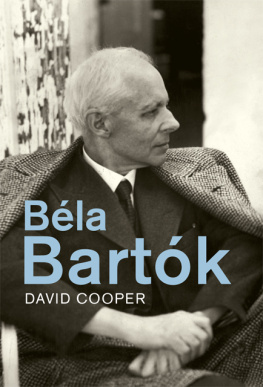

Bela Bartk / David Cooper.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-14877-0 (cl : alk. paper)

1. Bartk, Bla, 18811945. 2. ComposersHungaryBiography. I. Title.

ML410.B26C68 2015

780.92dc23

[B]

2014047980

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Oliver and Ellie

Contents

Illustrations

Figures

Tables

Preface

What a wee little part of a persons life are his acts and his words! His real life is led in his head, and is known to none but himself. All day long, and every day, the mill of his brain is grinding, and his thoughts (which are but the mute articulation of his feelings) not those other things, are his history. His acts and his words are merely the visible thin crust of his world, with its scattered snow summits and its vacant wastes of waterand they are so trifling a part of his bulk! a mere skin enveloping it. The mass of him is hiddenit and its volcanic fires that toss and boil, and never rest, night nor day. These are his life, and they are not written, and cannot be written. Every day would make a whole book of eighty thousand wordsthree hundred and sixty-five books a year. Biographies are but the clothes and buttons of the manthe biography of the man himself cannot be written.

Samuel Langhorne Clemens, writing under his nom de plume Mark Twain in the preface to his own autobiography, brilliantly expresses the fundamental dilemma of the genre. No human life, even (or particularly) ones own, can be reconstructed and no personality delineated in more than the barest outline. As for the events and opinions of a books protagonist, adduced as the objective points through which this profile is traced, their selection can reveal as much about the motivations of the biographer as his or her subject.

Although I have sought, wherever possible, the most credible sources for the Bartk revealed in the following pages, I must freely admit that this is but one of very many possible permutations of a narrative that could be constructed. The best one can hope is that this does not do him, or any of the other actors portrayed here, any serious disservice or injustice; and that this book communicates, albeit through a glass darkly, something of a life that was enormously rich and an output (as composer, performer, musicologist and pedagogue) that was extraordinary in terms of both its quantity and quality. There will, of course, be errors and mistakes, and for these I take full responsibility.

Bartk revealed himself not merely through his actions and words, but through his musical works. His scores are not timeless, ahistorical artefacts, but are contingent on the time and place of their composition. I thus took the decision to include the description and analysis of the pieces inline with a discussion of contemporaneous events, because these provide an important part of the context in which the works were composed, in biographical, geographical and intellectual terms. This does, necessarily, break the narrative flow of the composers outer life, but readers who are not interested in the technical niceties of a particular work can skim read or jump across these sections.

During the final year or so of Bartks life, first Ditta (his second wife) alone and then both of them together, lived in an apartment on West 57th Street in Manhattan. Another migr Hungarian couple lived in the same building, Pl and Erzsbet Kecskemti, and Bartk had enormous affection for them. Pl was a sociologist and philosopher, and Erzsi was one of Bartks former students who had apparently possessed one of the very few privately owned harpsichords in Hungary in the 1930s and had brought this with her to the USA. Pl, who would go on to work as a researcher for the RAND Corporation, had completed the first draft of his major work Meaning, Communication and Value in the early years of the Second World War, though it was not eventually published until 1952. he examined the autonomous values: religious orthodoxy, truth, justice and beauty. Bartk receives no mention in this monograph, but behind Kecskemtis theorisation of aesthetic value judgements one can imagine the conversations that took place between the two men.

While Kecskemti accepts the apparent spontaneity of aesthetic experience, he goes on to note that There is a characteristic attitude which corresponds to this aesthetic element: that in which appearing forms are envisaged purely as such, divorced from practical and private associations. Developing his argument he comments that:

the significance of the form of the aesthetic object may very well have representational and other associative factors. It is essential to the beauty of a landscape painting that it represent trees; but we do not perceive that beauty unless we go beyond the abstract, general idea that trees are represented and observe how beauty is achieved by the unique form of the trees in the picture. It is in this sense that we say that the significance of aesthetic form

The ability of individuals to perceive the aesthetic significance of forms may be partly innate, but it needs to be developed through education. The significance of form is not timeless; it bears the mark of the historical occasion, the climate of its creation. Its appeal, however, is not limited to that historical location. Paradoxically, however, Works bearing the signature of their time have timeless appeal.

Kecskemti recognises the need for immanent criticism the judgement of the work in terms of the body of doctrine underlying the style to which it belongs, but he accepts that there needs to be a balance between this and spontaneous sensibility and receptivity. He concludes this section of his discourse on beauty with the remark that:

A pattern of conformismnonconformism, characteristic of every field of value, is closely connected with the relatively rational factor in the creation and appreciation of art. Basic practices, techniques, conventions, and principles of the various arts must be learned from masters; but in this field, too, pupils may emancipate themselves. They are primarily helped in this by some articulate doctrine. Innovators in art are often theorists.

For Bartk, his masters were, in particular, Brahms, Liszt, Reger, Busoni, Richard Strauss, Debussy and Stravinsky, and their forms (in the widest sense of the term) reverberate through his output to the end of his life. As a theorist, unlike Schoenberg whose primary discourse was around tonal practice (in texts such as the Harmonielehre, Structural Functions of Tonal Music and Fundamentals of Musical Composition), Bartks most important contribution was through the cataloguing and analysis of traditional music (of Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, Serbo-Croatia, Turkey and Algeria). His emancipation as a composer was entirely bound up with the theorisation of these repertoires and this impacted his scores in a technical sense from the tiniest detail to the largest element in terms of structure, tonality, phrase length, scale type, melodic contour, texture and sonority.

Next page