This book is dedicated to the memory of those who taught me to respect and love the natural world: my mother, Vanne, who was my teacher, role model, and best friend for sixty-six years of my life; David Greybeard, Flo, and the other chimpanzees of Gombe; and that wonderful companion and teacher of my childhood, Rusty.

I dedicate this book to my mother, Beatrice, who embraces all that is good about the world and who selflessly blessed my life with peace, warmth, compassion, respect, and bountiful love.

I am also deeply indebted to all of the extraordinary dog-beings with whom I have lived and the wild animals whom I came to know, awe-inspiring individuals who selflessly enriched my life by sharing with me the spirit, magic, and essence of who they are. And special thanks to Jethro

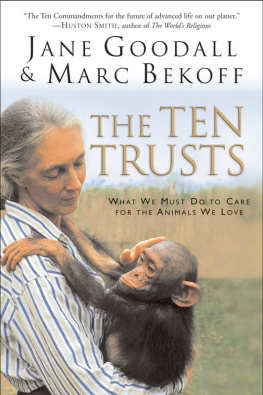

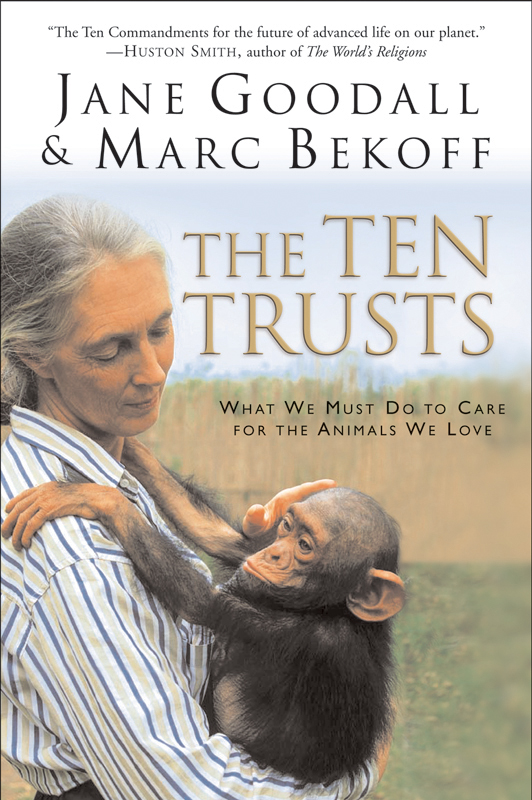

This book, written in collaboration with my colleague and friend Marc Bekoff, is our joint attempt to argue for a closer connection with the natural world and a more ethical attitude toward all the creatures that make up the multitude of species with whom we humans share this planet. We shall try to show that teaching our children and all people compassion for other animals and respect for the places where they live will create a safer and more tolerant world. It is written for all who have hopes for the future, for their children and grandchildren. We believe that only when we understand can we care, and that only when we care sufficiently will we help. And we believe, too, that if we do not pull together to prevent the further deterioration of the fragile health of our beautiful planet, any hope for the future is in vain. We have reached a critical point in our history.

The book is based on a series of mantras that came to Marcs mind as he hiked with his canine companion, Jethro, in November 1999. Even as he enjoyed the mountain scenery of Boulder, Colorado, where he lives and teaches, he pondered the problems that plague those of us who care about the environment and the future of life on Earth. On the eve of a new year, a new century, a new millennium, Marc thought about all that was wrong in the worldthe pollution, the destruction of habitat, global extinction of species throughout the world. For the first time in about three hundred years, in the year 2000, a primate had been pronounced officially extinct. Miss Waldrons colobus, a colorful monkey of the rain forests of Ghana, was goneforever. People were shocked to a degree not experienced when they hear of the tens of thousands of less conspicuous species that have become extinct during the century.

Marc was dreaming of a time when scientists and nonscientists alike would work toward the same goalcreating a world in which people respect and live in harmony with the natural world, leaving lighter footsteps as they move through life. A world where the desperation of poverty and hunger is a thing of the past, and there is equitable distribution of those things necessary for a good life. Above all, a world in which we humans live in peace with each other, with animals, and with nature. The things he and I had so often talked and faxed each other about over the preceding few years. The mantras that obsessed Marc were a series of steps that we, the stewards of this planet, must actively take in our own lives in order to preserve and protect it. They described how we could all become better and more compassionate inhabitants of Earth. He asked me if I would add my voiceand the mantras that resulted were published at the turn of the century in the Boulder Daily Camera . This book was a natural next step, expanding the ideas of those mantras, which we came to think of as trusts, as we are entrusted with the care of the animals and environments we love.

The Trusts central theme is one I have been talking and writing about since I began to study chimpanzees in 1960the importance and value of the individual. Not just the individual human being, but the individual animal being also. (Of course, we are animals too, but we use the word animal in its usual, everyday sense to refer to nonhuman animal beings.) And we argue that many animals, especially those with complex brains and central nervous systems, have personalities, emotions, and the ability to solve those problems likely to crop up in their worlds. We humans have a more sophisticated brain when it comes to intellectual problem solving, but animals are not simply machines, marching to the tune of innate or inborn instincts or drivesthey are able to make choices, to change direction according to need. Once we admit to this, we develop a new respect for these fellow travelers and, with it, new ethical concerns about our so often abusive treatment of them.

When I was twenty-six, Louis Leakey sent me into the field to study chimpanzees. I had no scientific training and had not been to university. He wanted the observations of a naive mind, uncluttered by the reductionist thinking of the ethologists of the time. Initially, most scientists discredited my observations as anecdotal and unscientific, especially when an article of mine appeared in the National Geographic . In those days, especially in Europe, it was bad form for a scientist to publish anything in the popular press. I was written off as a Geographic cover girl. But as my only goal was to discover the secrets of chimpanzee social life and I had already learned so much about animal behavior from my dog, Rusty, I was unconcerned by this attitude. The Ph.D. in ethology that I eventually earned from Cambridge University helped me to introduce my controversial ideas and methodology into mainstream science; compassion and science could work together after all.

Marc had a more conventional introduction to science than I did, but was also imbued with deep compassion toward the animals he studied. Gradually, over the years, he became increasingly disturbed by some of the methodology and the attitudes toward animals that he found in many of his colleagues in ethology and psychology. It was his collaboration with the philosopher Dale Jamieson that finally set Marc and me on the same platformspeaking out together for a more compassionate scientific attitude.