Spellings of some words in quotations have been Americanized from the British versions for consistency and ease of reading. Italics have been maintained to preserve the original emphasis.

Prior to July 1, 1867, present-day Canada was referred to as British North America. For the sake of clarity and simplicity, this book employs the term Canada in place of British North America.

P ROLOGUE

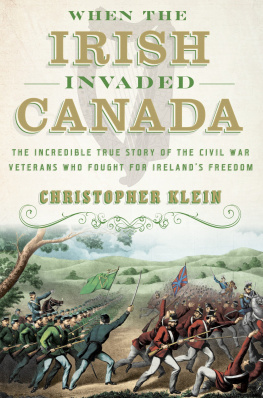

T HIRTEEN MONTHS AFTER Robert E. Lee laid down his sword at Appomattox Court House, former Confederate rebels slipped on their gray wool jackets. Union veterans longing to emancipate an oppressed people donned their blue kepis. Battle-hardened warriors from both the North and the South returned to the front lines, but not to reignite the Civil War. Instead, the former foes became improbable brothers in arms united against a common enemyGreat Britain.

Entwined by Irish bloodlines, the private army that congregated on the south side of Buffalo, New York, on the night of May 31, 1866, shared not just a craving for gunpowder but a yearning to liberate their homeland from the shackles of the British Empire. For seven hundred years, British rulers attempted to extinguish Irelands religion, culture, and language, and when the potato crop failed in the 1840s and 1850s, causing one million people to die, some Irish believed that the British were trying to exterminate them as well.

Many of the two million refugees fleeing the Great Hunger washed ashore in the United States, where the newcomers continued to face the scorn of nativist Know-Nothings who believed the Irish had no intention of assimilating into American culture but plotted to take handout after handout while imposing papal law on their adopted home. Even from a distance of nearly fifteen years and three thousand miles, the trauma remained raw for many of the insurgents who enlisted in the self-proclaimed Irish Republican Army. Radicalized by their collective ordeal, these Irish American Civil War veterans viewed their service in the bloody crucibles of Bull Run, Antietam, and Gettysburg as training for the real fight they wanted to wageone to free Ireland.

Wearing green ribbons tied to their hats and fastened to their buttonholes, eight hundred Irish paramilitaries who had traveled from as far away as New Orleans emerged from the boardinghouses and saloons of Buffalos Irish enclave, the First Ward, on a clear spring night. Carrying green flags sewn by their wives, girlfriends, and mothers and hauling nine wagons laden with secretly stockpiled rifles and ammunition, the Irish Republican Army set off on one of the most fantastical missions in military historyto kidnap Canada.

Bred to hate the British, the thirty-two-year-old colonel John ONeill was fulfilling his boyhood dream as he led the Irish Republican Army on its march northward. The governing passion of my life apart from my duty to my God is to be at the head of an Irish Army battling against England for Irelands rights, he declared. For this I live, and for this if necessary I am willing to die.

ONeill could neither forgive the British for the unspeakable horrors that he had witnessed as a boy coming of age during the Great Hunger nor forget his grandfathers soul-stirring tales of seventeenth-century ancestors who dared to take up arms against the Crown. Although they did not deliver freedom to Ireland, the young lad learned that just the mere act of fighting the British could render an Irishman a hero.

Even after taking a Confederate bullet in defense of the Union, ONeill never forgot the plight of his homeland. Lured by its plan to strike the British province of Canada, which was directly ruled by London, he enlisted in the Irish Republican Army after the Civil War. ONeill saw the logic in targeting the British Empire at its most accessible pointon the other side of Americas porous northern borderinstead of an ocean away in Ireland, a plan that had failed repeatedly over the centuries.

Canada is a province of Great Britain; the English flag floats over it and English soldiers protect it, he wrote. Wherever the English flag and English soldiers are found, Irishmen have a right to attack.

Far from some whiskey-fueled daydream, the plan for the Irish invasion of Canada had been carefully crafted for months by veteran Civil War officers, including the one-armed general Thomas William Sweeny. Keen students of military history, the Irishmen knew that attacking Canada had been as time-honored an American tradition as fireworks on the Fourth of July. In fact, even before John Hancock affixed his signature to the Declaration of Independence, the Continental army had launched its first major assault of the American Revolution by storming into Quebec.

In the first American century, the United States and Canada were hardly peaceful neighbors. Old-timers in Buffalo could recall when British soldiers breached the border during the War of 1812 and burned the nascent village to the ground in retaliation for similar measures by U.S. forces. American anger toward Canada surged during the Civil War, when the British colony became a haven for draft dodgers, escaped prisoners of war, and Confederate agents who plotted covert operations including raids on border towns, the firebombing of New York City, and the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

Given Great Britains tacit support for the Confederacy and American hopes that Canada would become the next territory to be absorbed as the country continued to fulfill its Manifest Destiny, President Andrew Johnson was more than willing to let the Irish Republican Army twist the tail of the British lion. The U.S. government sold surplus weapons to the Irish militants, and Johnson met personally with their leaders, reportedly giving them his implicit backing. The Irishmen had been free to establish their own state in exilecomplete with its own president, constitution, currency, and capitol in the heart of New York City.