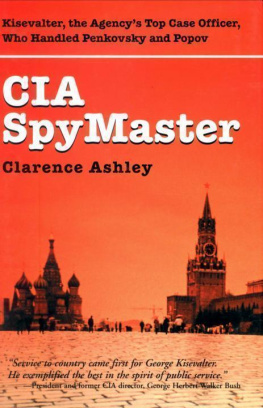

CIA SpyMaster

SpyMaster

Clarence Ashley

Foreword by Leonard McCoy

For George's old buddies in the clandestine operations group, who went

unheralded, who did not get medals, and yet who continued on in their

service, rewarded only by the self-satisfaction that they received from

knowing that they had done something worthwhile.

Contents

Part I: The Good Soldier

Chapter 1 27

Chapter 2 43

Chapter 3 52

Chapter 4 64

Part II: Popov

Chapter 5 81

Chapter 6 98

Chapter 7 109

Chapter 8 116

Chapter 9 127

Part III: Penkovsky

Chapter 10 141

Chapter 11 154

Chapter 12 189

Chapter 13 205

Chapter 14 214

Chapter 15 227

Part IV: The Reluctant Warrior

Chapter 16 237

Chapter 17 246

Chapter 18 252

Chapter 19 264

Chapter 20 277

Chapter 21 290

Chapter 22 307

Foreword

George Kisevalter's story is part of the epic struggle during the last century to determine which set of governing principles would prevail in civilized societies. The world from which he came, Tsarist Russia, was dying. But even as he left it for America in 1915, a new one was forming, one with new leaders determined to wrench Russia out of its feudal traditions, relieve the oppression inflicted for centuries on the majority of its rural population, and set it on a path of industrialization and economic growth befitting its potential. Any such objective, with the great obstacles and uncharted course its champions faced, however, was obliterated by the cunning and vicious assault led against the nascent Russian democracy by a coterie of Marxist theorists. The civil war that their actions provoked then raged on in George's background. One after another, his friends and relatives were swept up into the war or driven out of Russia and into a drifting population that journeyed to all corners of the globe, often only to spend a generation and then move on.

While its origins may be different, the violent end to Tsarist rule in Russia had remarkable similarity to the changes precipitated in America by its own Civil War. The Russian serfs and the American slaves had occupied similar positions in their respective societies, and their liberation was a crucial theme in the two civil wars. In Russia, however, liberation was only a slogan, a rhetorical theme, mobilizing the serfs to help subjugate those elements that opposed the seizure of power by Marxist theorists. The nobility of Russia, of* course, were natural enemies of those about to launch an irrational social experiment across a region whose area was one-sixth of the land mass of the entire world. As with the slave-holding families of the old South, the Russian upper classes contributed to the circumstances of their downfalls, but the consequences of the years of violence that then descended upon the two societies were diametrically opposite. Whereas America erased the blot of slavery that overshadowed the nation's developing grandeur, Soviet Russia brought forth tyranny that was to generate wave after wave of callous and brutal exploitation of its people for the benefit of its unprincipled leadership, the so-called "Nomenklatura."

The ensuing problems in U.S.-Soviet relations during the 1920s and 1930s abruptly seemed irrelevant, however, when both nations were drawn into World War II as allies in the fight with Germany. At that time, George became an integral and unique part of the U.S. effort to supply massive amounts of war materiel to the USSR. The period of direct contact between the national military teams formed in this common goal nonetheless demonstrated a lack of Soviet gratitude as well as a high degree of Soviet suspicion of Americans and American motives. The war was hardly won when the U.S. began to discover overwhelming evidence of hostile espionage activity conducted against the U.S. by its ally, the Soviet Union.

The postwar conflict between the U.S. and Soviet societies threatened more than once to involve the world in a new conflagration that could mean the end of the human race. Nevertheless, awareness of its involvement in this mortal conflict by a trusting, idealistic, even naive America was slow in coming. Some Americans, like many in other countries, were deceived by Soviet propaganda into collaborating in the oppression of the Russian people as well as the people of Eastern Europe and Asia. Even when defectors came to the U.S. out of the Soviet regime and revealed some of its tyranny, listeners too often doubted the news' validity as well as the motives of the messengers, or erroneously minimized the damage that Soviet espionage and propaganda were then inflicting upon America.

Fully appreciating the conflict between these two nations was the preoccupation of the adult life of George and is the basis of the debt that we all owe him. The profession in which he become a giant was first abolished in the United States as the war ended, then was reestablished as Soviet political intentions in Eastern Europe-and Soviet espionage against the U.S.-became apparent. The newly formed Central Intelligence Agency then began to assemble information from all sources to help us to understand the Soviet leadership, their intentions, their plans, and their capabilities. Draconian controls on Soviet society made this task practically impossible, while Soviet threats and hostile actions, particularly in Berlin, intensified. A nuclear confrontation between the two countries seemed ineluctably closer with each crisis. The requirement for accurate and detailed information on Soviet intentions grew ever more urgent. At precisely this point, George took his place in the Plato's cave shadows of Cold War history.

In 1953 the United States still knew very little about the Soviet regime and its plans. Early that year, a Soviet Military Intelligence officer in the Soviet Southern Group of Forces occupying Austria volunteered to provide the U.S. with significant information. George took his Russian heritage, his extensive knowledge of Russian history, as well as his masterful fluency in the Russian language to Vienna and met the officer. The interview provided our first indepth knowledge of Soviet military capabilities. More importantly, it began to give us insight into the Soviet mentality as it viewed the western world-and particularly the United States. The American government consequently began to develop some confidence that it could evaluate Soviet intentions, and that it had a reliable glimpse into Soviet capabilities. The CIA then realized that George was the only individual capable of efficiently working with this agent. George followed the officer to Germany in 1956 and maintained the flow of invaluable information until the man's ultimate return to Moscow in 1958.

Perhaps George's most vital contribution to our national security came in 1961, when a Soviet Military Intelligence officer senior to George's former contact provided information of staggering value. Again, the CIA reaffirmed its belief that only George was the appropriate conduit for the stream of information this man was to provide. The Secret Intelligence Service of the United Kingdom concluded the same. This Soviet officer had access to the highest levels of the Soviet government and over the next two years, the intelligence information that accrued from this liaison significantly elevated our level of confidence in dealing with the USSR. This increased understanding of Soviet thinking may well have drawn us back from the very brink of nuclear war on at least two occasions: the Berlin crisis during the autumn of 1961 and the Cuban missile crises in October of 1962. George's remarkable knowledge of Russian history and language and, above all, his immutable love and understanding of his fellow man, Russian or otherwise, provided much of the intelligence on which our national policies were based until the collapse of the USSR. Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that George played an important part in ensuring our very existence.