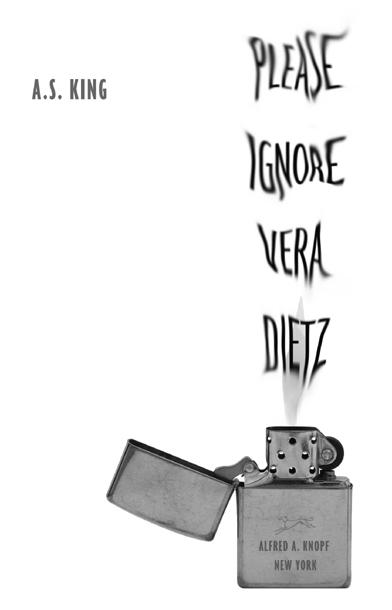

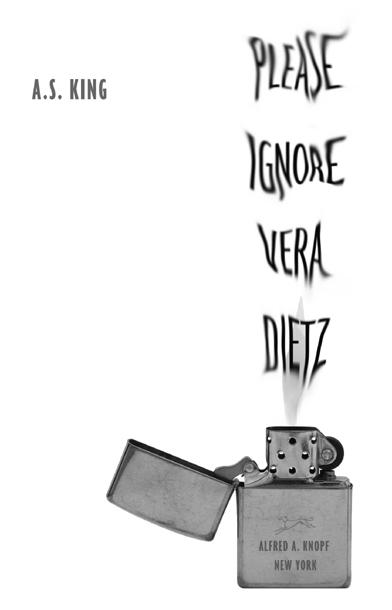

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright 2010 by A.S. King

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Random House Childrens Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Visit us on the Web! www.randomhouse.com/teens

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at www.randomhouse.com/teachers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

King, A. S. (Amy Sarig)

Please ignore Vera Dietz / by A.S. King. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Summary: When her best friend, whom she secretly loves, betrays her and then dies under mysterious circumstances, high school senior Vera Dietz struggles with secrets that could clear his name.

eISBN: 978-0-375-89617-0

[1. Best friendsFiction. 2. FriendshipFiction. 3. SecretsFiction. 4. DeathFiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.K5693Pl 2010

[Fic]dc22

2010012730

Random House Childrens Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

For my parents, who taught me about

flow charts and everything else .

Contents

What is your original face, before your mother and father were born?

Zen koan

PROLOGUE

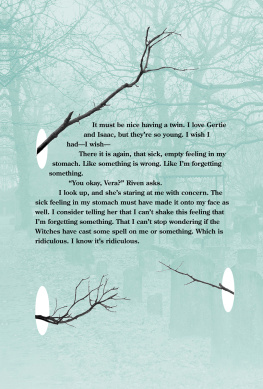

Before I died, I hid my secrets in the Master Oak.

This book is about my best friend, Vera Dietz, who eventually found them.

Charlie Kahn

(the pickle on Veras Big Mac)

To say my friend died is one thing.

To say my friend screwed me over and then died five months later is another.

Vera Dietz

(high school senior and pizza delivery technician)

PART ONE

THE FUNERAL

The pastor is saying something about how Charlie was a free spirit. He was and he wasnt. He was free because on the inside he was tied up in knots. He lived hard because inside he was dying. Charlie made inner conflict look delicious.

The pastor is saying something about Charlies vivacious and intense personality. I picture Charlie inside the white coffin, McDonalds napkin in one hand, felt-tipped pen in the other, scribbling, Tell that guy to kiss my white vivacious ass. He never met me. I picture him crumpling the note and eating it. I picture him reaching for his Zippo lighter and setting it alight, right there in the box. I see the congregation, teary-eyed, suddenly distracted by the rising smoke seeping through the seams.

Is it okay to hate a dead kid? Even if I loved him once? Even if he was my best friend? Is it okay to hate him for being dead?

Dad doesnt want me to see the burying part, but I make him walk to the cemetery with me, and he holds my hand for the first time since I was twelve. The pastor says something about how we return to the earth the way we came from the earth and I feel the grass under my feet grab my ankles and pull me down. I picture Charlie in his coffin, nodding, certain that the Great Hunter meant for everything to unfold as it has. I picture him laughing in there as the winch lowers him into the hole. I hear him saying, Hey, Veerits not every day you get lowered into a hole by a guy with a wart on his nose, right? I look at the guy manning the winch. I look at the grass gripping my feet. I hear a handful of dirt hit the hollow-sounding coffin, and I bury my face in Dads side and cry quietly. I still cant really believe Charlie is dead.

The reception is divided into four factions. First, you have Charlies family. Mr. and Mrs. Kahn and their parents (Charlies grandparents), and Charlies aunts and uncles and seven cousins. Old friends of the family and close neighbors are included here, too, so thats where Dad and I end up. Dad, still awkward at social events without Mom, asks me forty-seven times between the church and the banquet hall if Im okay. But really, hes worse off than I am. Especially when talking to the Kahns. They know we know their secrets because we live next door. And they know we know they know.

Im so sorry, Dad says.

Thanks, Ken, Mrs. Kahn answers. Its hot outsidefirst day of Septemberand Mrs. Kahn is wearing long sleeves.

They both look at me and I open my mouth to say something, but nothing comes out. I am so mixed up about what I should be feeling, I throw myself into Mrs. Kahns arms and sob for a few seconds. Then I compose myself and wipe my wet cheeks with the back of my hands. Dad gives me a tissue from his blazer pocket.

Sorry, I say.

Its fine, Vera. You were his best friend. This must be awful hard on you, Mrs. Kahn says.

She has no idea how hard. I havent been Charlies best friend since April, when he totally screwed me over and started hanging out full-time with Jenny Flick and the Detentionhead losers. Let me tell youif you think your best friend dying is a bitch, try your best friend dying after he screws you over. Its a bitch like no other.

To the right of the family corner, theres the community corner. A mix of neighbors, teachers, and kids that had a study hall or two with him. A few kids from his fifth-grade Little League baseball team. Our childhood babysitter, who Charlie had an endless crush on, is here with her new husband.

Beyond the community corner is the official-people area. Everyone there is in a black suit of some sort. The pastor is talking with the school principal, Charlies family doctor, and two guys I never saw before. After the initial reception stuff is over, one of the pastors helpers asks Mrs. Kahn if she needs anything. Mr. Kahn steps in and answers for her, sternly, and the helper then informs people that the buffet is open. Its a slow process, but eventually, people find their way to the food.

You want anything? Dad asks.

I shake my head.

You sure?

I nod yes. He gets a plate and slops on some salad and cottage cheese.

Across the room is the Detentionhead crowdCharlies new best friends. They stay close to the door and go out in groups to smoke. The stoop is littered with butts, even though theres one of those hourglass-shaped smokeless ashtrays there. For a while they were blocking the door, until the banquet hall manager asked them to move. So they did, and now theyre circled around Jenny Flick as if shes Charlies hopeless widow rather than the reason hes dead.

An hour later, Dad and I are driving home and he asks, Do you know anything about what happened Sunday night?

Nope. A lie. I do.

Because if you do, you need to say something.

Yeah. I would if I did, but I dont. A lie. I do. I wouldnt if I could. I havent. I wont. I cant yet.

I take a shower when I get home because I cant think of anything else to do. I put on my pajamas, even though its only seven-thirty, and I sit down in the den with Dad, who is reading the newspaper. But I cant sit still, so I walk to the kitchen and slide the glass door open and close it behind me once Im on the deck. There are a bunch of catbirds in the yard, squawking the way they do at dusk. I look into the woods, toward Charlies house, and walk back inside again.

You going to be okay with school tomorrow? Dad asks.

No, I say. But I guess its the best thing to do, you know?

Probably true, he says. But he wasnt there last Monday, in the parking lot, when Jenny and the Detentionheads, all dressed in black, gathered around her car and smoked. He wasnt there when she wailed. She wailed so loud, I hated her more than I already hated her. Charlies own mother wasnt wailing that much.

Next page