Also by Vera Caspary

books

The White Girl

Ladies and Gents

Music in the Street

Thicker Than Water

Laura

Bedelia

Stranger Than Truth

The Weeping and the Laughter

Thelma

The Husband

Evvie

Bachelor in Paradise

A Chosen Sparrow

The Man Who Loved His Wife

The Rosecrest Cell

Final Portrait

The Dreamers

The Secret of Elizabeth

films

The Night of June 13th

Such Women Are Dangerous

Easy Living

Laura

Bedelia

Letter to Three Wives

Three Husbands

Out of the Blue

Les Girls

Bachelor in Paradise

plays

Blind Mice

(with Winfred Lenihan)

Geraniums in My Window

(with Samuel Ornitz)

Laura

(with George Sklar)

Wedding in Paris

(musical comedy)

The

Secrets

of

Grown-Ups

Vera Caspary

All rights reserved, including without limitation the right to reproduce this ebook or any portion thereof in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

First Edition published 1979 by McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Copyright 1979, 2013 by Vera Caspary estate

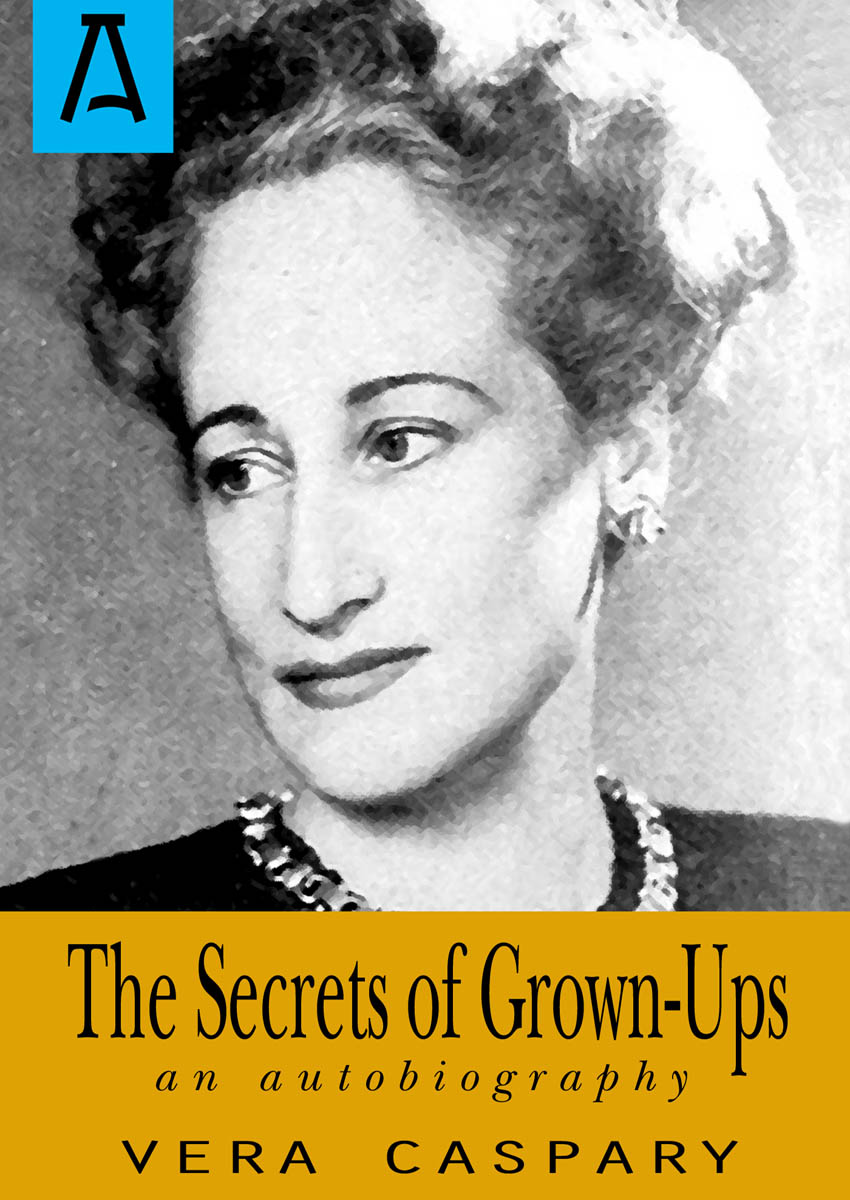

Cover photograph of Vera Caspary by Alfredo Valente, used courtesy of the Estate of Alfredo Valente.

ISBN: 978-1-5040-2902-5

Distributed in 2016 by Open Road Distribution

180 Maiden Lane

New York, NY 10038

www.openroadmedia.com

For

Judy and

Michael and

Daniel and

Zachary

Book One

1. The Secrets of Grown-Ups

A specter haunts my ego. For most of my life I have tried to escape this ghoul, bury her in a respectable family plot, lock her in a closet smelling of old womens dresses. Tenacious and spiteful, she rises out of memory, laughing, mocking me with memories of failed dreams. Like everyone else in this contradictory world, I have two definite and well-developed sides, one that I show off and one I am afraid to see plain. So much of my life has been given to the exploitation of the exhibited side that the hidden self, the specter, has to be hunted down, smoked out of secret cells, stripped of disguise.

I see her now, a caricature of my showcase image, a skinny girl shivering as the Chicago wind sweeps across the Wells Street station of the South Side El. She is eighteen or nineteen and convinced that her life is a failure. She is cousin to my ugly old-maid cousins, who have devoted all their days (and, of necessity, their nights) to their dear mother and have never had husbands, lovers or fun; she is sister to my sister, a snob who talked loftily of culture, disdaining those who cared more for clothes and jewelry than for art and poetry, but who wanted more than anything else to be seen in the glittering garments of the rich; she is neighbor to my dull neighbors who played bridge and talked about clothes and the high cost of living; she is a stenographer among stenographers eternally trapped among the filing cases with men dedicated to percentages of profit. Saddest of all, she is a writer among those secretly writing in locked bedrooms the poem, the short story, the novel that will never be published.

As she rides on the South Side express, shoved, pushed, swaying, member of an ill-smelling crowd, she forces herself to look at scenes that, on brighter days, her eyes avoid. Open to the gaze of El passengers are the windows and lives of the poor of Chicagos Black Belt. She sees squalor as evidence of futility. Nothing really matters, she whispers again and again as in prayer. The nihilism brings perverse consolation. The South Side El will not travel through eternity, the loathed office job cannot last forever, and in the end she, along with the other passengers and the blacks in the squalid rooms, will die as unimportantly as flies squashed against a screen.

She was wrong, of course. To the passionate mind everything matters. In a full life no incident is without meaning, no element so important as change. Our century has seen so much of revolution and on so many levels that for women, especially, the historic role has been turned upside down. To have known the changes of this dynamic century is to have lived in drama such as no genius has conceived.

I was born by accident in the nineteenth century. No one expected me on that November day, certainly not my mother, who had kept her shameful secret concealed under loose house robes. When she had learned that she was pregnant at an age then considered next door to senility (she was well over forty), she was facing a major operation and believed herself entitled to an abortion. Our Dr. Frankenstein, young and scrupulous, refused to hear her pleas. Lacking courage to consult a more cooperative doctor, Mama played the role of invalid and took to tea gowns which concealed her scandalous condition. When I made my untimely escape from the womb, Mamas friends, sisters-in-law and grown children were honestly shocked. When she first laid eyes on the unfinished product my mother hoped the little monster would not last until the twentieth century. In November it was impossible to move a fragile infant to a hospital, so they rigged up a do-it-yourself incubator out of a wash basket which nurses kept filled with hot-water bottles in a room kept at an even temperature. After I had shown that I could survive the clothes basket, hot-water bottles, wet nurse and special formulas, Mama not only adjusted to what had seemed the horror of having a baby at her age but regarded me as something of a miracle. The rest of the familymy father, two grown brothers and a sisterloved, spoiled and bossed me outrageously. Aunts, uncles, cousins and family friends never dared enter our house without bringing tribute to the baby.

No child ever received more presents or thoughtless of them. Nothing material had value for me except in the receiving. I broke or lost dolls, mittens, lockets, crayons, balls, bracelets, pennies and pencils; left toys wherever I dropped them and looked for more when the doorbell rang. In the same way I received the petting and adulation, but along with it was forced to accept their various ideas of discipline. Not unnaturally I became a self-centered little girl, loving but rebellious, since the things I learned in my early years were confusing and untidy.

I cannot remember the naughtiness for which Papa gave me the only spanking I recall, but I can still see the frightened little girl being carried up the stairs, laid across dark blue knees, unbuttoned and smacked. It probably did not hurt much because Papa could not have been cruel to Baby, but the humiliation left a permanent scar. Papa unbuttoning my pants! Papa seeing my behind! He was my first idol, a strong and ardent man, gifted at love and passionate in honesty. Do you know what your name means? hed ask. Truth. A girl named Vera can never tell a lie.

This made me a clumsy and uncomfortable liar. Even the trifling falsehoods of social life, excuses for tardiness, broken dates, forgotten promises, have caused acute discomfort. Not that I can claim a life entirely free of deceit. During high school years my chum and I spent fifty-one cents at Walgreens penny sale for two boxes of Dorine cake rouge. Every school-day, after saying goodbye to my mother and sister, Id hurry into the bathroom, rub pink circles into my cheeks, tuck the rouge into the toe of a shoe at the back of the closet and race out before Mama or Sister caught sight of a painted countenance that would have disgraced the Caspary name.