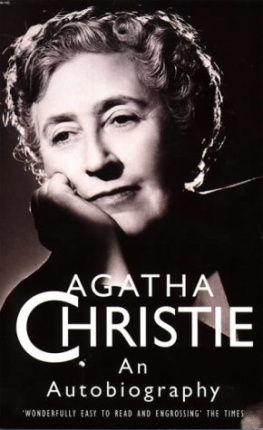

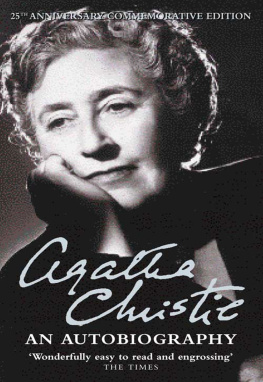

Agatha Christie began to write this book in April 1950; she finished it some fifteen years later when she was 75 years old. Any book written over so long a period must contain certain repetitions and inconsistencies and these have been tidied up. Nothing of importance has been omitted, however: substantially, this is the autobiography as she would have wished it to appear.

She ended it when she was 75 because, as she put it, it seems the right moment to stop. Because, as far as life is concerned, that is all there is to say. The last ten years of her life saw some notable triumphsthe film of Murder on the Orient Express; the continued phenomenal run of The Mousetrap; sales of her books throughout the world growing massively year by year and in the United States taking the position at the top of the best-seller charts which had for long been hers as of right in Britain and the Commonwealth; her appointment in 1971 as a Dame of the British Empire. Yet these are no more than extra laurels for achievements that in her own mind were already behind her. In 1965 she could truthfully writeI am satisfied. I have done what I want to do.

Though this is an autobiography, beginning, as autobiographies should, at the beginning and going on to the time she finished writing, Agatha Christie has not allowed herself to be too rigidly circumscribed by the strait-jacket of chronology. Part of the delight of this book lies in the way in which she moves as her fancy takes her; breaking off here to muse on the incomprehensible habits of housemaids or the compensations of old age; jumping forward there because some trait in her childlike character reminds her vividly of her grandson. Nor does she feel any obligation to put everything in. A few episodes which to some might seem importantthe celebrated disappearance, for exampleare not mentioned, though in that particular case the references elsewhere to an earlier attack of amnesia give the clue to the true course of events. As to the rest, I have remembered, I suppose, what I wanted to remember, and though she describes her parting from her first husband with moving dignity, what she usually wants to remember are the joyful or the amusing parts of her existence.

Few people can have extraced more intense or more varied fun from life, and this book, above all, is a hymn to the joy of living.

If she had seen this book into print she would undoubtedly have wished to acknowledge many of those who had helped bring that joy into her life; above all, of course, her husband Max and her family. Perhaps it would not be out of place for us, her publishers, to acknowledge her. For fifty years she bullied, berated and delighted us; her insistence on the highest standards in every field of publishing was a constant challenge; her good-humour and zest for life brought warmth into our lives. That she drew great pleasure from her writing is obvious from these pages; what does not appear is the way in which she could communicate that pleasure to all those involved with her work, so that to publish her made business ceaselessly enjoyable. It is certain that both as an author and as a person Agatha Christie will remain unique.

NIMRUD, IRAQ. 2 April 1950.

Nimrud is the modern name of the ancient city of Calah, the military capital of the Assyrians. Our Expedition House is built of mud-brick.

It sprawls out on the east side of the mound, and has a kitchen, a livingand dining-room, a small office, a workroom, a drawing office, a large store and pottery room, and a minute darkroom (we all sleep in tents).

But this year one more room has been added to the Expedition House, a room that measures about three metres square. It has a plastered floor with rush mats and a couple of gay coarse rugs. There is a picture on the wall by a young Iraqi artist, of two donkeys going through the Souk, all done in a maze of brightly coloured cubes. There is a window looking out east towards the snow-topped mountains of Kurdistan. On the outside of the door is affixed a square card on which is printed in cuneiform BEIT AGATHA (Agathas House).

So this is my house and the idea is that in it I have complete privacy and can apply myself seriously to the business of writing. As the dig proceeds there will probably be no time for this. Objects will need to be cleaned and repaired. There will be photography, labelling, cataloguing and packing. But for the first week or ten days there should be comparative leisure.

It is true that there are certain hindrances to concentration. On the roof overhead, Arab workmen are jumping about, yelling happily to each other and altering the position of insecure ladders. Dogs are barking, turkeys are gobbling. The policemans horse is clanking his chain, and the window and door refuse to stay shut, and burst open alternately. I sit at a fairly firm wooden table, and beside me is a gaily painted tin box with which Arabs travel. In it I propose to keep my typescript as it progresses.

I ought to be writing a detective story, but with the writers natural urge to write anything but what he should be writing, I long, quite unexpectedly, to write my autobiography. The urge to write ones autobiography, so I have been told, overtakes everyone sooner or later. It has suddenly overtaken me.

On second thoughts, autobiography is much too grand a word. It suggests a purposeful study of ones whole life. It implies names, dates and places in tidy chronological order. What I want is to plunge my hand into a lucky dip and come up with a handful of assorted memories.

Life seems to me to consist of three parts: the absorbing and usually enjoyable present which rushes on from minute to minute with fatal speed; the future, dim and uncertain, for which one can make any number of interesting plans, the wilder and more improbable the better, sinceas nothing will turn out as you expect it to doyou might as well have the fun of planning anyway; and thirdly, the past, the memories and realities that are the bedrock of ones present life, brought back suddenly by a scent, the shape of a hill, an old songsome triviality that makes one suddenly say I remember with a peculiar and quite unexplainable pleasure.

This is one of the compensations that age brings, and certainly a very enjoyable oneto remember.

Unfortunately you often wish not only to remember, but also to talk about what you remember. And this, you have to tell yourself repeatedly, is boring for other people. Why should they be interested in what, after all, is your life, not theirs? They do, occasionally, when young, accord to you a certain historical curiosity.

I suppose, a well-educated girl says with interest, that you remember all about the Crimea?

Rather hurt, I reply that Im not quite as old as that. I also repudiate participation in the Indian Mutiny. But I admit to recollections of the Boer WarI should do, my brother fought in it.

The first memory that springs up in my mind is a clear picture of myself walking along the streets of Dinard on market day with my mother. A boy with a great basket of stuff cannons roughly into me, grazing my arm and nearly knocking me flat. It hurts. I begin to cry. I am, I think, about seven years old.

My mother, who likes stoic behaviour in public places, remonstrates with me.

Think, she says, of our brave soldiers in South Africa.

My answer is to bawl out: I dont want to be a brave soldier. I want to be a cowyard!

What governs ones choice of memories? Life is like sitting in a cinema. Flick! Here am I, a child eating clairs on my birthday. Flick!

Two years have passed and I am sitting on my grandmothers lap, being solemnly trussed up as a chicken just arrived from Mr Whiteleys, and almost hysterical with the wit of the joke.

Just momentsand in between long empty spaces of months or even years. Where was one then? It brings home to one Peer Gynts question: