image

image

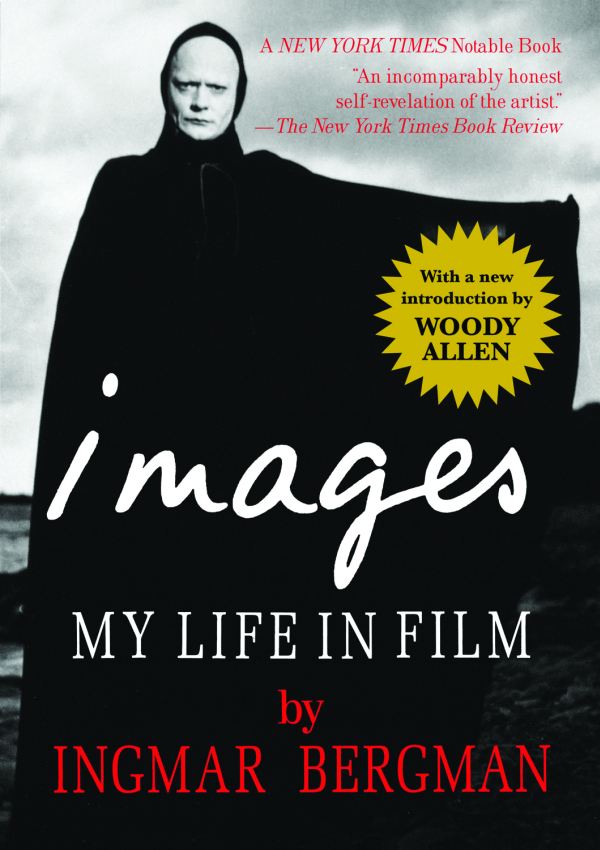

My Life in Film

I ngmar B ergman

Translated from the Swedish by

Marianne Ruuth

Introduction by

Woody Allen

Arcade Publishing New York

Copyright 1990, 2011 by Cinematograph AB

Translation copyright 1994, 2011 by Arcade Publishing, Inc.

Introduction 2007, 2011 by Woody Allen

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61145-041-5

Printed in China

My play opens with an actor walking down into the audience, where he strangles a critic, then reads aloud from a little black book all the humiliations he has noted therein. Then he throws up on the audience, after which he exits and puts a bullet through his head.

Workbook, July 19, 1964

NOTE

A number of Ingmar Bergmans films were released in the United States and Great Britain under different titles. In this book the first mention lists both titles wherever possible, with the British title appearing between parentheses. Subsequently, either title may be used.

Contents

The comedies

Smiles of a Summer Night

Introduction

THE MAN WHO ASKED HARD QUESTIONS

I GOT THE NEWS IN OVIEDO, a lovely little town in the north of Spain where I was shooting a movie, that Bergman had died. A phone message from a mutual friend was relayed to me on the set. Bergman once told me he didnt want to die on a sunny day, and not having been there, I can only hope he got the flat weather all directors thrive on.

Ive said it before to people who have a romanticized view of the artist and hold creation sacred: In the end, your art doesnt save you. No matter what sublime works you fabricate (and Bergman gave us a menu of amazing movie masterpieces) they dont shield you from the fateful knocking at the door that interrupted the knight and his friends at the end of The Seventh Seal. And so, on a summers day in July, Bergman, the great cinematic poet of mortality, couldnt prolong his own inevitable checkmate, and the finest filmmaker of my lifetime was gone.

I have joked about art being the intellectuals Catholicism, that is, a wishful belief in an afterlife. Better than to live on in the hearts and minds of the public is to live on in ones apartment, is how I put it. And certainly Bergmans movies will live on and will be viewed at museums and on TV and sold on DVDs, but knowing him, this was meager compensation, and I am sure he would have been only too glad to barter each one of his films for an additional year of life. This would have given him roughly sixty more birthdays to go on making movies; a remarkable creative output. And theres no doubt in my mind thats how he would have used the extra time, doing the one thing he loved above all else, turning out films.

Bergman enjoyed the process. He cared little about the responses to his films. It pleased him when he was appreciated, but as he told me once, If they dont like a movie I made, it bothers me for about thirty seconds.He wasnt interested in box office results, even though producers and distributors called him with the opening weekend figures, which went in one ear and out the other. He said, By midweek their wildly optimistic prognosticating would come down to nothing. He enjoyed critical acclaim but didnt for a second need it, and while he wanted the audience to enjoy his work, he didnt always make his films easy on them.

Still, those that took some figuring out were well worth the effort. For example, when you grasp that both women in The Silence are really only two warring aspects of one woman, the otherwise enigmatic film opens up spellbindingly. Or if you are up on your Danish philosophy before you see The Seventh Seal or The Magician, it certainly helps, but so amazing were his gifts as a storyteller that he could hold an audience riveted and enthralled with difficult material. Ive heard people walk out after certain films of his saying, I didnt get exactly what I just saw, but I was gripped on the edge of my seat every frame.

Bergmans allegiance was to theatricality, and he was also a great stage director, but his movie work wasnt just informed by theater; it drew on painting, music, literature and philosophy. His work probed the deepest concerns of humanity, often rendering these celluloid poems profound. Mortality, love, art, the silence of God, the difficulty of human relationships, the agony of religious doubt, failed marriage, the inability for people to communicate with one another.

And yet the man was a warm, amusing, joking character, insecure about his immense gifts, beguiled by the ladies. To meet him was not to suddenly enter the creative temple of a formidable, intimidating, dark and brooding genius who intoned complex insights with a Swedish accent about mans dreadful fate in a bleak universe. It was more like this: Woody, I have this silly dream where I show up on the set to make a film and I cant figure out where to put the camera; the point is, I know I am pretty good at it and I have been doing it for years. You ever have those nervous dreams? or You think it will be interesting to make a movie where the camera never moves an inch and the actors just enter and exit frame? Or would people just laugh at me?

What does one say on the phone to a genius? I didnt think it was a good idea, but in his hands I guess it would have turned out to be something special. After all, the vocabulary he invented to probe the psychological depths of actors also would have sounded preposterous to those who learn filmmaking in the orthodox manner. In film school (I was thrown out of New York University quite rapidly when I was a film major there in the 1950s) the emphasis was always on movement. These are moving pictures, students were taught, and the camera should move. And the teachers were right. But Bergman would put the camera on Liv Ullmanns face or Bibi Anderssons face and leave it there and it wouldnt budge and time passed and more time and an odd and wonderful thing unique to his brilliance would happen. One would get sucked into the character and one was not bored but thrilled.

Bergman, for all his quirks and philosophic and religious obsessions, was a born spinner of tales who couldnt help being entertaining even when all on his mind was dramatizing the ideas of Nietzsche or Kierkegaard. I used to have long phone conversations with him. He would arrange them from the island he lived on. I never accepted his invitations to visit because the plane travel bothered me, and I didnt relish flying on a small aircraft to some speck near Russia for what I envisioned as a lunch of yogurt. We always discussed movies, and of course I let him do most of the talking because I felt privileged hearing his thoughts and ideas. He screened movies for himself every day and never tired of watching them. All kinds, silents and talkies. To go to sleep hed watch a tape of the kind of movie that didnt make him think and would relax his anxiety, sometimes a James Bond film.

Next page