ingmar bergman

ingmar bergman

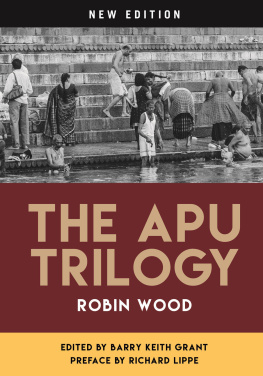

New Edition

Robin Wood

Edited by Barry Keith Grant

wayne state university press detroit

contemporary approaches to film and media series A complete listing of the books in this series can be found online at wsupress.wayne.eduGeneral Editor

Barry Keith Grant

Brock University

Advisory Editors

Robert J. Burgoyne

Frances Gateward

University of St. Andrews

California State University, Northridge

Caren J. Deming

Tom Gunning

University of Arizona

University of Chicago

Patricia B. Erens

Thomas Leitch

School of the Art Institute of Chicago

University of Delaware

Peter X. Feng

Walter Metz

University of Delaware

Southern Illinois University

Lucy Fischer

University of Pittsburgh

New edition 2013 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

17 16 15 14 13

5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wood, Robin, 19312009.

Ingmar Bergman / Robin Wood ; edited by Barry Keith Grant New ed.

p. cm. (Contemporary approaches to fi lm and media series) Includes bibliographical references and index.

Filmography:

p.

ISBN 978-0-8143-3360-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8143-3806-3 (e-book) 1. Bergman, Ingmar, 19182007Criticism and interpretation. I. Grant, Barry Keith, 1947 II. Title.

PN1998.A3B469 2012

791.430233092dc23

2012010812

Typeset by Newgen North America

Composed in Dante

Photos are from the collections of the Robin Wood estate and the editor.

To Gran Persson,

who taught me to think about Bergman

contents

contents

viii

foreword

Ingmar Bergman is the third book by infl uential fi lm critic Robin Wood to be republished by Wayne State University Press within its Contemporary Approaches to Film and Media Series. Like

Woods other early auteurist studies, Ingmar Bergman was an in-fl uential milestone when it was fi rst published in 1969. At a time when few reviewers and critics were taking fi lm study seriously, Woods careful and thoroughly cinematic commentary demonstrated the potential of fi lm analysis in a nascent scholarly fi eld.

It infl uenced a generation of students and cineastes.

Woods great contribution as an analyst of Bergmans fi lms is to make a compelling case for the logic of the fi lmmakers development over a period of some twenty years while still

respecting the distinctiveness of each individual fi lm. Wood constantly compares and contrasts the Bergman movies under

discussion, pointing out similar themes, motifs, symbolism, and narrative strategies. He is especially insightful on how Bergman utilized a stock company of actresses for multiple appearances in different fi lms. The astuteness of Woods insights into Bergmans work is clear when one considers how well they apply to the fi lms Bergman made after the book was published.

It is not only the books insights into Bergmans fi lms but also its style and distinctive voice that make it an important

foreword

work of fi lm criticism. Ultimately Woods greatest achievement as a writer is to communicate a passion for fi lms and their seriousnessa message that is, alas, at least as pressing today as it was in 1969. Back then, no one seriously interested in movies read this book without feeling an equally passionate response, nor will readers today. Woods voice is unmistakably his own, and his tone is wont to provoke. Because Wood is both dog-matic and transparent, the cruxes in his critical terminology so obvious, it is more productive, and certainly more exhilarating, to disagree with him than to be persuaded by most other writers on fi lm. In short, as a work of criticism, Ingmar Bergman is exemplary in eloquence and insight.

From the vantage point of today, however, over forty years

since the books appearance and the successful establishment of fi lm studies in academia, it might appear to some that the book is, as they say, dated. After all, Wood completed it before Bergman made such important later fi lms as The Passion of Anna,Cries and Whispers, From the Lives of the Marionettes,Scenes froma Marriage, and Fanny and Alexander. A signifi cant part of Bergmans career, which included many of his fi lms for television, was still to come when the original book, which ended with a perceptive discussion of Bergmans great 1968 fi lm Shame, was published. This incompleteness is perhaps most poignant in

Woods comment that Bergman was interested in mounting a

production of The Magic Flute, a project the fi lmmaker did indeed successfully bring to the screen in 1975.

It is unfortunate that Wood did not get to revise the book

as part of a projected plan to revisit several of his early monographs for Wayne State University Press on the model of what x

foreword

he had already famously done with his work on Alfred Hitch

cock. The only one he had managed to do before his death was the volume on Howard Hawks, which was published by the

Press in 2006. At one time Wood told me that he wanted to revise his Bergman and Satyajit Ray volumes next, and he looked forward excitedly to doing so. Undoubtedly, the astonishingly and always perceptive Wood, by incorporating new ideas from

his own subsequent development as a critic, a development

quite as remarkable in its way as Bergmans, would have offered new insights on the directors important later fi lms as well as on such ill-conceived projects as The Touch and The Serpents Egg.

Thus one might think of Ingmar Bergman as an incomplete account of one of the worlds most protean fi lmmakers from one of the worlds most resourceful critics, with much of each ones future development uncharted here. The book noticeably lacks anything resembling what became accepted as Theory in fi lm studies for decades after its publication. Throughout its pages Wood offers pronouncements on the western cultural tradition with complete assurance, in a manner that contemporary scholars would not dare since such terms have become, in the postmodern era, far more hotly contested. Woods common-sensical defense of that tradition, and his framing of Bergman as a fellow-defender, may strike some contemporary readers either as surprisingly conservative or as quaint Leavisite piety.

Yet it would be incorrect to conclude that Ingmar Bergman lacks a critical stance. Indeed, one of its central values is that it is perhaps the best elucidation of what is regarded as Woods early humanist perspective. The critics deep knowledge of Bergmans fi lms and his unerring sense of their place in a larger xi

foreword

cultural conversation impart an enviable authority even to his seemingly casual remarks. It is true that the book was written before Woods transition to his Marxist/feminist/gay liberation position, but it is apparent to anyone who has paid close attention to his work that the popular notion of these two phases

of Woods career is simplistic if not fallacious. Woods emphasis on questions of value (What makes a work important? How

Next page