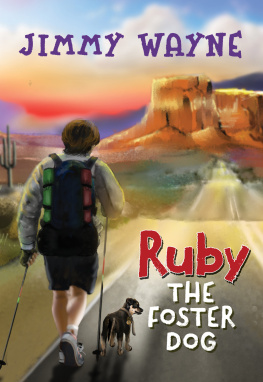

Dedication

In memory of my mother-in-law, Gladys Ruth King, who gave me the idea for this novel

Acknowledgements

With thanks to my sister-in-law, Pauline Masterson, who helped with the typing of the manuscript; and to Lord McColl of Dulwich and Dr Ian Hannah for their invaluable assistance relating to medical details in this book. Thank you also to my sister, Teresa Deere, who helped me to acquire a word processor, and to my brother, Tony Masterson, who taught me how to use it. A special thank you to my niece, Claire Guntrip, for keeping my children busy while I worked; and to the staff at Welling Library, for supplying me with reference books.

PART ONE

1887

Chapter One

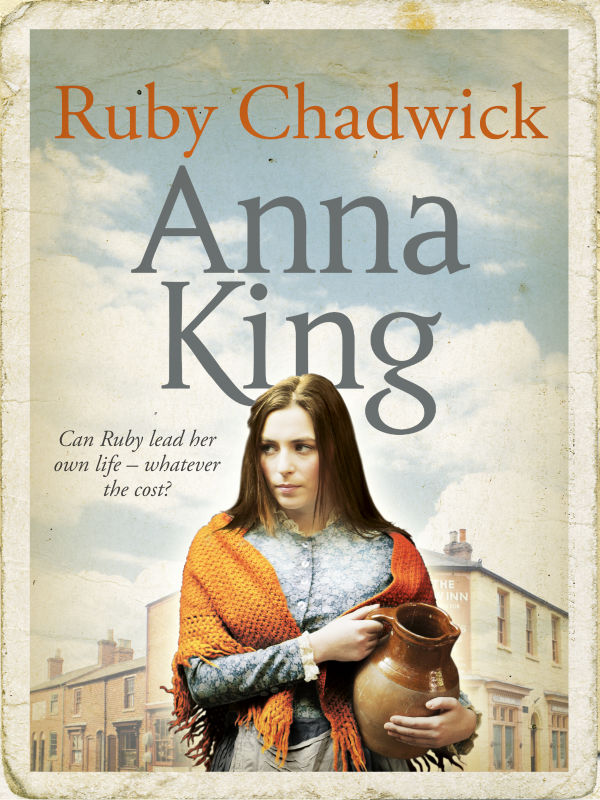

Beneath the pile of blankets a silent form stirred, a small leg appeared through a gap in the bed-covers, encountered the icy cold and was swiftly pulled back into the warmth. The sounds from the street carried up to her window as ten-year-old Ruby Chadwick tried to hang on to the last vestige of sleep. A womans voice, shrill with raucous laughter, brought Rubys head from her soft warm pillow.

Blast! she swore softly, her hands cupping the sides of her face as her long chestnut hair, parted into segments with cotton curling-rags, tumbled around her shoulders. Swinging her legs over the side of the bed, she shivered slightly before pulling off the coverlet and wrapping it round her slight frame. Half running, half hopping, she made her way across the cold floorboards to her bedroom window to look for the person who had so rudely awakened her.

The woman stood on the pavement, her heavily-painted face illuminated by the huge wrought-iron gas lamp that hung over the pub entrance below Rubys bedroom. On her head she wore a huge hat bedecked with multi-coloured feathers, her tattered green dress cut low at the neck revealing her soiled, much used breasts. By her side stood a seaman, his cap pushed to the back of his head, a drunken grin on his face.

As Ruby pressed closer against the window, his voice came clearly to her: Will sixpence do yer?

The woman cocked her head to one side as if considering the offer, then, shrugging her shoulders, she nodded. Arm in arm, the couple walked forward towards the door directly underneath Rubys window. She watched as the sailor tried to pull the woman in the opposite direction.

Lets ave a drink first, eh, love? wheedled the woman.

The sailor stopped in his tracks, his fuddled mind trying to come to a decision. He had docked only two hours ago after a year at sea, but his pay was almost gone and he still had to find somewhere to sleep tonight, unless he could find his way home to his wife in Stepney. Pushing away the womans arm, he stood back as if to see her more clearly, and then shuddered. His wife was no oil-painting, but at least she was clean and, more important, she didnt cost anything.

Sorry, love, changed me mind. Got a wife an ten kids at ome. I avent seen em for over a year.

Seeing the look that came over the womans face, he hastily backed away, looking fearfully over his shoulder in case she had an accomplice waiting in one of the dark alleys that lined the street. He wouldnt be the first sailor to be found unconscious, a lump on his head and his pockets empty. Turning swiftly on his heel, he made off down the street, ignoring the stream of invective that followed him, anxious now to get to the safety of his home.

Still at her vantage place, Ruby watched the change in the woman. Gone now was the inviting smile; in its place came the face of an old woman, weary and drawn, a defeated look Ruby had witnessed many times from her window. Letting the lace curtains drop back, she scuttled back to her bed, muttering under her breath, Doxy!

The scene Ruby had just witnessed was a common occurrence, especially on a Saturday night. She lived over the Kings Arms public house in the Mile End Road and often bemoaned her misfortune at having to sleep in the bedroom directly over the bar and facing the street. If the noise from downstairs didnt disturb her sleep, the passing traffic almost certainly would. As she snuggled back down under the covers, she wondered how her two brothers managed to sleep so soundly in the box-room next door.

Yawning loudly, she settled down in the feather-tick bed, closing her eyes. Within minutes she was asleep.

Three hapence of gin, Guvnor?

Bernard Chadwick looked into the wrinkled face of the old woman, and then down at the counter to make sure the money was there. Swiftly scooping up the coppers, he turned to the bar behind him and picking up a coloured glass from the shelf he proceeded to measure out the three-hapence-worth of gin from a yellow bottle. Returning to the counter, he set the drink down before moving on to his next customer.

The Kings Arms was one of the many public houses that lined the Mile End Road, but Bernard Chadwick liked to think that his establishment was a cut above its fellows. The bar was spacious, the floor covered in clean sawdust and sand every Friday morning, the coloured drinking glasses were kept clean and well polished, as was the large looking-glass that ran the length of the bar and reflected the yellow, green and red bottles that lined the shelves beneath. At this time of the evening, just an hour from midnight, all the wooden tables and chairs were taken.

The East End women sat holding their pints of gin as they conversed about the days events; their children, often left alone while their parents frequented the gin palaces; and the latest fashion. As most of the women present hadnt had a new dress for the past 20 years or more, this conversation piece was somewhat academic, but to these women, born to a life of poverty, the public houses were their equivalent of the gentrys drawing rooms. And so they sat in regal supremacy, their grimy dresses showing the tattered petticoats beneath, until it was time to return to the hovels they called home.

Their menfolk stood, tankards of ale held between strong, often calloused, hands, holding forth on the topic of the day. This usually fell between two subjects, politics and religion. The arguments would rage back and forth, for the most part in good-natured camaraderie, but it would be a very dull Saturday night if the evening didnt end with a fight outside on the cobbled pavement. If the combatants were women, the entertainment was heightened considerably.

Daisy Chadwick stood at the far end of the bar counter, looking down on the dwindling plates of sandwiches and meat pies, wondering if she should replenish the food supply so vital to their trade. Raising her eyes, she looked down the length of the counter to try to catch her husbands attention, but Bernard was at that moment serving one of their more respectable customers, a costermonger and his wife from nearby Whitechapel market, their smart clothes singling them out from the rest of the crowd. Daisy could see Bernards face wreathed in smiles, the happy face he saved for his well-to-do clientele. She doubted if any of their regular customers had ever seen this side of his countenance, for in the past few years he had found it harder not to show the contempt he felt, had always felt, for the poverty-stricken people of the East End.

Daisy could remember clearly the first time she had seen him. She had been with her parents on a weeks holiday to Southend, and they had met while walking on the promenade. She could still remember his earnest face as hed talked about his dream of owning a hotel and public house combined. The exact location of this dream home Bernard had never quite divulged, but Daisy had always been under the impression that it would be in her beloved Essex. Even after all these years, she still thought of Essex as her home. She still missed the green fields and clean streets streets that didnt run with filth and clean people, especially clean people. They had married three months after their first meeting. Their short honeymoon had been a weekend in Brighton, and then he had brought her here to her new home. She had been so much in love that she had never queried where they would be living after the wedding; she had trusted him implicitly. The only thing shed known was that they would be renting a moderately large public house from the brewery while they saved for a better place.