Table of Contents

DEDICATION

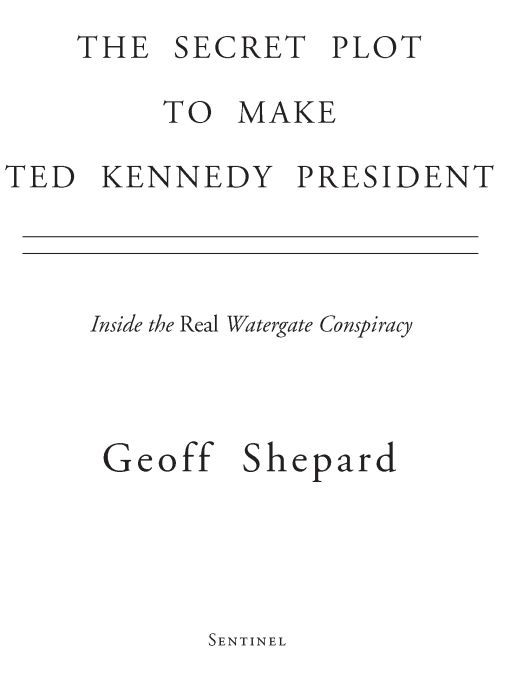

The Watergate Special Prosecution Force was established with the appointment of Archibald Cox on May 25, 1973. Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974, but the savage onslaught did not finally end until June of 1977well after the Democrats had regained control of the White House and vastly increased their majorities in both houses of Congress.

Charles Ruff, the fourth special prosecutor (and later counsel to President Bill Clinton), observed in a farewell interview with Bob Woodward that he expected his work on Watergate to be questioned someday, saying there are judgment calls that were made that people can legitimately question.

Ruff assured Woodward that, should he be called to testify at such an inquiry, Id say, Gee, I just dont remember what happened back then, and they wont be able to indict me for perjury and that, maybe, thats the principal thing that Ive learned in four years.... I just intend to rely on that failure of memory.

This book marks the beginning of that inquiry, and is dedicated to the thousands of Republicanscandidates, supporters, contributors, and all of their familieswhose aspirations were thwarted, whose careers were ended, and whose lives were ruined in the single-minded effort to destroy them and the GOPto the end that Ted Kennedy might become president and the restoration of Camelot finally be achieved.

PREFACE

After graduating from both Whittier College in 1966 and Harvard Law School in 1969, I took a job with a law firm in Seattle. At the same time I applied for a White House Fellowshipalthough I knew that the odds of winning one of those highly competitive slots were slim at best.

Richard Nixon himself coincidentally had been responsible for my interest in the Fellows program. In 1965, shortly after being elected student body president at Whittier, also Nixons alma mater, I was informed that I had been selected to receive that years annual Nixon scholarship ($250, which at that time was not an insubstantial amount) from the Whittier Republican Womens Club.

It turned out that Nixon had agreed to present the award in person, and I was seated at the head table next to the former vice president. When he rose to speak, he didnt talk about politics or national affairs. Instead, he set about comparing his experiences at Whittier with mine. We had both, he said, won student body elections. We both had been on the college debate team and active in the societies (the Quaker equivalent of on-campus fraternities). He then reviewed his life in politics, but kept bringing everything back to his years at Whittier. He finished on a graceful note, saying that, having gotten to know me during lunch, he hoped I might go even further than he had. I left with quite a swollen head in addition to the very welcome boost in financial aid.

About a week later, I was called to the deans office for an even greater surprise. Nixon apparently had thought so much of our lunch together that when he got back to New York he wrote a personal check for another $250thus doubling my scholarship. There was no press release or public acclaim to be had; he simply thought I would benefit from the additional help. Years later this personal act of kindness was the determining factor in my decision to apply for a White House Fellowship in his administration.

The Fellows program was proposed by Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare John Gardner and established by President Johnson in 1964. The idea was to select a few young men and women in the early stages of promising careers and bring them to Washington. Each would be assigned either to the White House staff or to a cabinet member for a year of concentrated study and high-level government experience. They would return to their jobs and their communities with an enhanced understanding of (and possibly an increased desire someday to serve in) the federal government.

Each years class of Fellows is chosen by a national selection process, which typically begins with a thousand applicants. After national, regional, and local interview panels winnow the numbers, some thirty finalists spend a weekend being grilled and evaluated by the members of the presidentially appointed Commission on White House Fellowships. In the end, an average of fifteen is selected.

I was among those chosen for the class of 1969-70. Not yet twenty-five years old, I was among the youngest ever selected for the programbefore or since. I asked to be assigned to the Treasury Department, where I had the privilege of working with Undersecretary Paul A. Volcker. At the end of the Fellowship year, I was invited to join John Ehrlichmans Domestic Council staff, and made the short move from the Treasury building on the west side of the White House to the Old Executive Office building on the east side. In both places the grandeur of my surroundings (the high vaulted ceilings, the heavy carved doors, the patterned parquet floors) reflected the excellence of nineteenth-century craftsmanship rather than my entry-level position on the power grid.

It was very apparent that White House chief of staff H. R. (Bob) Haldeman ran a very tight ship. There were certain expectations of all the young professionals, especially those in policy-making positions on Ehrlichmans Domestic Council staff, and they were made quite clear from the outset. Nixon didnt like face-to-face discussions of policy issues with anyone except his three direct reports: Haldeman, Ehrlichman, and Henry Kissinger. With these three alone, he frequently thought out loud in wide-ranging discussions that included a great deal of venting and anger and frustrationmuch to his later disgrace when the White House tapes became known and were made public.

Haldeman was the doorkeeper who enforced the requirement that all issues reach the presidents desk in writing and via one-page cover memos on top of however much backup material was considered necessary. Very few staff members could draft papers to Nixons satisfaction. Slowly at first, I became the drafter of choice for papers on many domestic issues. In retrospect, I dont think that my success was because I wrote like a lawyer (since a good many of us were lawyers); it had to do with a shared experience at Whittier.

More than thirty years apart, both Nixon and I had taken Dr. Albert Uptons semantics course. Upton, a demanding and charismatic teacher, explored the ambiguity of words and stressed the importance of the proper use of language as the adjunct of logical thought. I think that Nixon, however unconsciously, recognized and appreciated the Uptonian influence on my writing.

In reviewing my files from those days, I discovered that in five years on the Domestic Council staff I prepared almost a thousand memos analyzing myriad domestic issues involving the Departments of Justice, Treasury, State, and Defense. Only a hundred or so were directly addressed to the president, but a lot of my other work was included in discussions or papers that did reach him.

I was a member of Richard Nixons staff for over five of the six years he was president. Ultimately, I became associate director of the Domestic Council. I knew all of the White House people who became involved with Watergate. I had worked with most of them; I was friends with many of them. I remember some with particular clarity. For example, I had a meeting with G. Gordon Liddy when he came back (as I learned much later) from reconnoitering the office of Daniel Ellsbergs psychiatrist for the break-in he conducted a week later. I asked him why his hand was heavily bandaged. He said it was because, while trying to light his pipe, he had become distracted by a pretty girl and inadvertently set the book of matches on fire. It turned out he had really burned his hand by placing it over a candle in order to demonstrate to his fellow burglars how much pain he could endure.