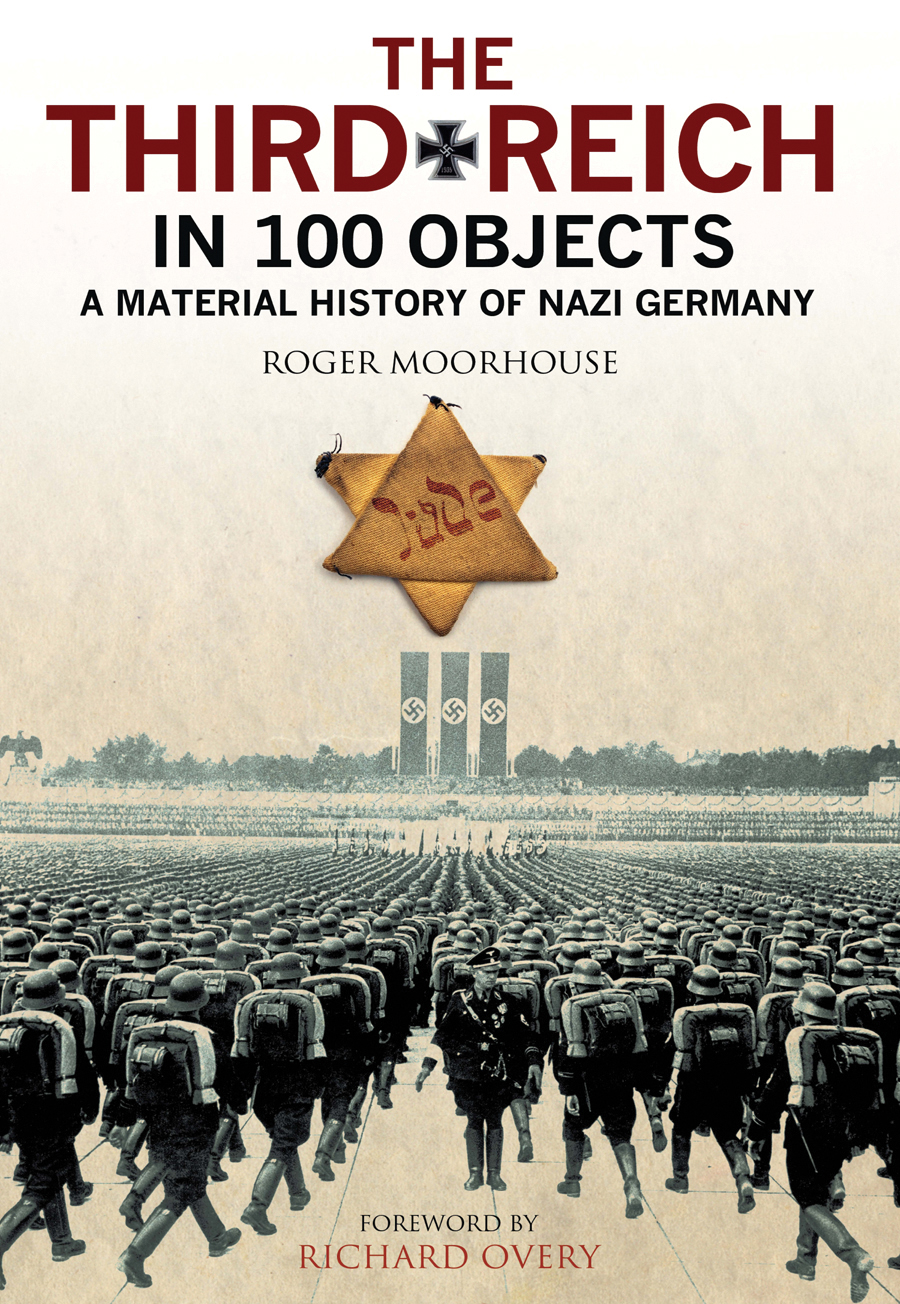

The Third Reich in 100 Objects

This edition published in 2017 by

Greenhill Books,

c/o Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley,

S. Yorkshire, S 70 2 AS

www.greenhillbooks.com

ISBN: 9781784381806

eISBN: 9781784381820

Mobi ISBN: 9781784381813

All rights reserved.

Roger Moorhouse, 2017

Foreword Richard Overy, 2017

The right of Roger Moorhouse to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the

Copyrights Designs and Patents Act 1988.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

Designed by Jem Butcher

For Nic & Eve with love

FOREWORD

Hitlers Third Reich lasted only twelve years , yet it continues to exert a macabre fascination long after its violent demise. There is no other modern political movement and no other modern dictator that can compete with the instant recognition of the images, symbols and propaganda surrounding Hitler and his regime. The swastika, adapted by Hitler himself from the traditional Hindu symbol of good fortune, is still daubed on walls by anti-fascists and neo-fascists because it enjoys such a powerful resonance even today. When the British comedy actor John Cleese chose to poke fun at the Germans in an episode of Fawlty Towers in the 1970s, his raised arm was all he needed to evoke in his audience an instant reminder of the hundreds of thousands of Germans in newsreel footage with their arms stretched out as far as they could go towards their adored Fhrer . The image of Hitler himself, with the neat black moustache and the limp forelock, has been superimposed on hundreds of election posters and advertising hoardings, or exploited in political cartooning. He enjoys as bizarre a celebrity status in death as he did in life.

Hitler with an excited young admirer at his Berghof retreat in happy prewar days.

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter, one of the crucial elements in Germanys early-war military successes.

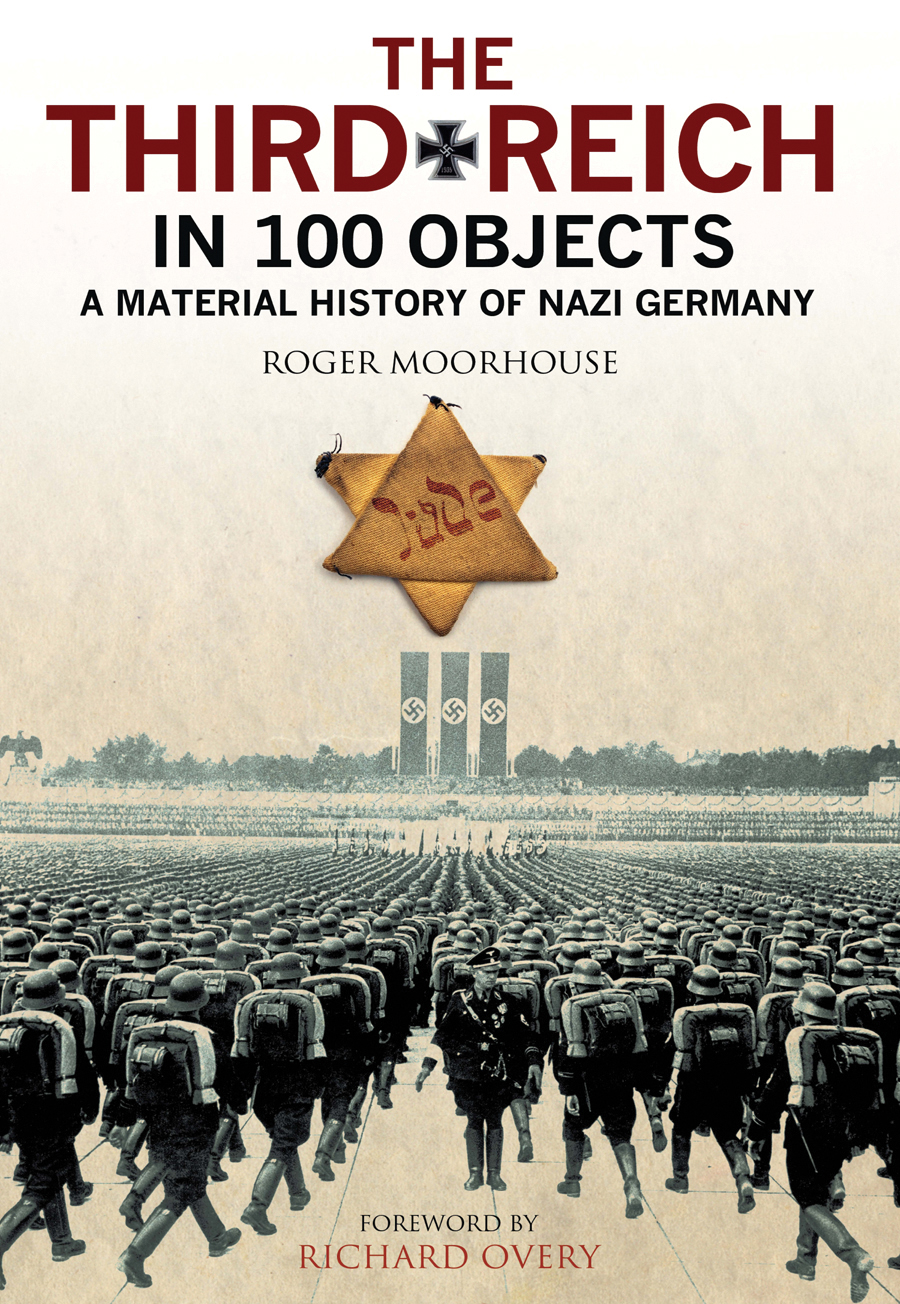

Image was all-important to Hitler and the National Socialist Party that he led. Visibility was one of the key explanations for their electoral success in the early 1930s, a quality that almost all other German political parties ignored. The image of Hitler himself was massaged all the time to show him alternately as the stern, unyielding messiah of the German people, or as the genial, unpretentious leader happy to pat small children and play with his dog. Hitler was completely absorbed by the image he presented as his political persona; no photograph of the leader wearing glasses was allowed to be published. The Party was also image-conscious. Its public face depended on the showy marches, the torchlight processions, the flags and symbols a carefully staged and choreographed political drama to make the movement distinctive. The Nuremberg rallies became orchestrated and disciplined expressions of the national revolution, impressive even by todays standards. The high point of this political artistry was reached in the Leni Riefenstahl film, Triumph of the Will , which conveys simply through image the powerful message of national revival and a single peoples community. The imagery itself encourages participation and belonging. The Heil Hitler! greeting and the Swastika flag draped from the bedroom window were as often as not spontaneous expressions of affirmation. Symbolism replaced the need to think very seriously about what it all meant.

The regime also generated a darker symbolism, evident in the choice of objects presented here. If there is no rubber truncheon, there are concentration camp relics, and the slogan Arbeit macht frei work makes you free which greeted prisoners at Auschwitz and other camps where work was usually a physical torture, or in many cases a prelude to early death. The name of the dreaded Gestapo, the political secret police, is still a byword for vicious oppression, though unlike the SS organisation with its black uniforms, silver badges and ornate daggers, the Gestapo is not immediately recognisable by any external trappings. The secret police were policemen, doing political detective work, or later pursuing Jews in hiding, and remain even today a more anonymous element in the history of the Hitler dictatorship than they should be. The SS, on the other hand, were designed to be seen, admired or feared. The black uniform and deaths head badge were an inspiration, a menacing fashion statement that the manure-coloured uniform of the SA could never match. The SS as a result features in the 100 objects a good deal.

Some of the symbols exploited by the regime were fatal in their consequences. In autumn 1941 Hitler finally ordered all German Jews to wear a yellow star sewn onto their clothing. The yellow star, first used in medieval Europe to distinguish Jews, was adapted by the regime for its policy of racial exclusion. Jews in all of German-occupied Europe were made to wear the star, which eventually made it easier to collect and deport them to their deaths in the extermination camps. The Jewish Star of David was visible from the start of the dictatorship when it was daubed on shop windows or the houses of Jewish attorneys and doctors to warn Germans not to buy goods or services from Jews. The caricature of the Jew was used widely in all party newspapers, a familiar narrow-eyed, hook-nosed figure clutching money-bags or menacing German womanhood.

The heart of evil: the rail tracks and gate at the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp.

The Reichsadler or Imperial Eagle, chosen by Hitler to be emblematic of the Third Reich.

Of course, choosing 100 objects to define the Third Reich can never be an easy task, and there will be things here that readers think should be included, just as there are many objects that will be reassuringly familiar. The selection below shows many different aspects of the story of Hitler, his rise to power and the dictatorship that followed. Taken together they provide a broad approach to the complex history of the period, and a set of images that give the history a firm material texture. The commentaries on each object are a reminder, however, that nothing is ever as simple as it seems. The objects need interpretation and context, whether they are as mundane as the brush Hitler used for his moustache, or as momentous as the volumes of Mein Kampf , Hitlers personal account of his brief life and the philosophy that informed it. The Third Reich was both ordinary and extraordinary, both daily life and malign drama. The 100 objects give a sense of those contrasts and of the way leaders and led experienced them.