Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

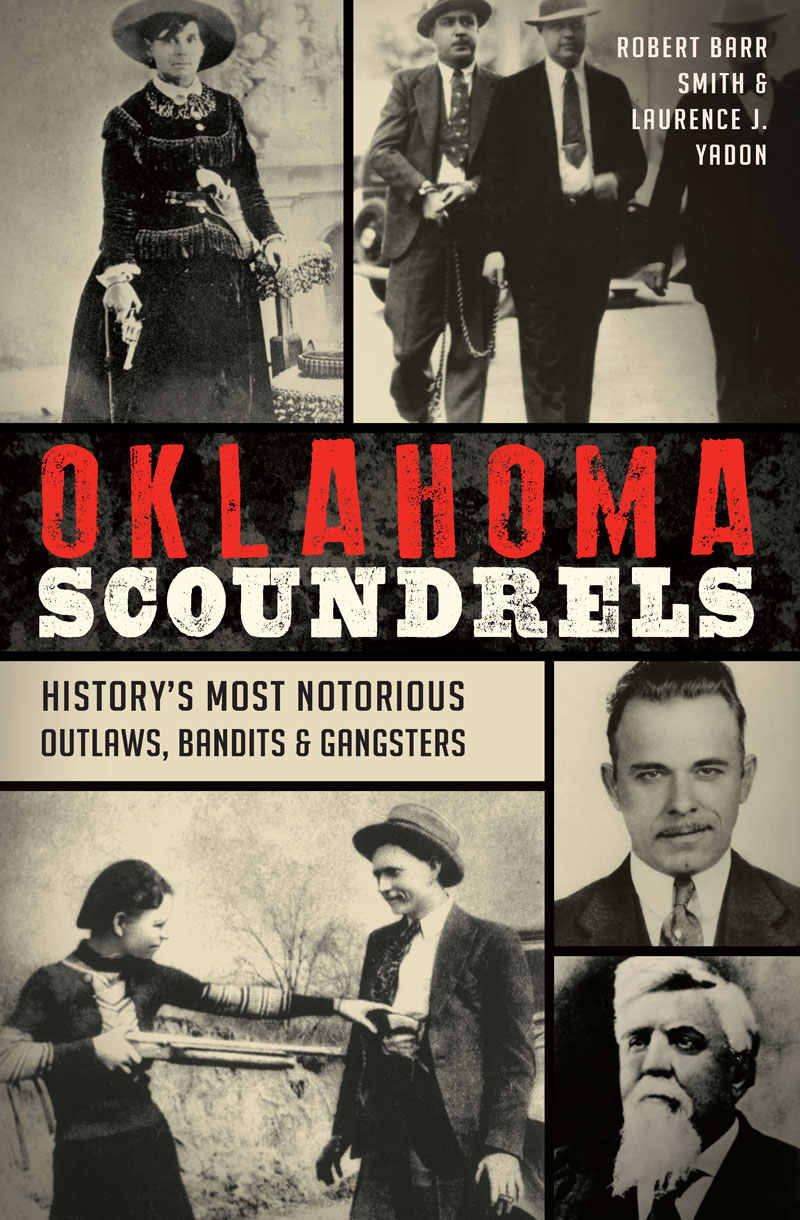

Copyright 2016 by Robert Barr Smith and Laurence J. Yadon

All rights reserved

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.62585.790.3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016943513

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.519.1

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The land we now call Oklahoma was wild and violent from its earliest days, from the creation of Indian Territory in 1830 as a refuge for the Indian tribes forced out of Tennessee, Georgia and Alabama. The Five Civilized Tribes, as the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek and Seminole tribes were eventually known, maintained no jails or prisons in the early years. Instead, justice generally followed two simple paths: whipping for minor offenses and a firing squad for the rest.

Their tribal justice systems at first relied on mounted police, called the Lighthorse. Over the vast expanse of Indian Territory, the Lighthorse not only investigated crime and made arrests but also appointed judges and juries and saw to punishmentall according to written rules. Save for occasional abuses, the system worked well. Except for one problem.

Tribal jurisdiction was very limited. A tribes Lighthorse law officersay, the Creek policecould arrest only members of his own tribe, adopted members and men of other tribes who had committed crimes within the Creek Nation. The jurisdiction of the United States was similarly complex: a deputy marshal could arrest only United States citizens. A marshal could apprehend an Indian only if the crime was against a U.S. citizens or involved alcohol (bootlegging being the perennial curse of the territory).

Early on, federal officers were largely limited to serving arrest warrants from the District Court in Fort Smith and returning prisoners to that busy tribunal. Unless reward money was available, the officers were paid only a puny per diem; they got nothing at all for a bad man killed resisting arrest.

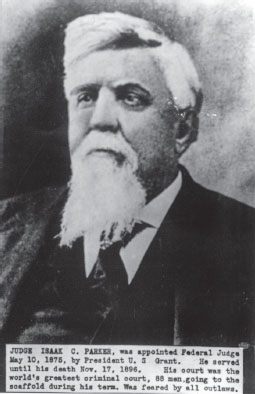

Hanging Judge Isaac Parker. Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries .

The two systems sometimes clashed. The worst conflict came in 1872 near the Arkansas border at Going Snake Schoolhouse, then being used as a temporary tribal courthouse. U.S. officers tried to arrest the defendant, the court objected and the resulting shootout with court personnel, spectators and even the defendant left at least ten men dead and the defendant on the run.

Three years later, Judge Isaac Parker was appointed to the federal bench in Fort Smith, a huge jurisdiction about the size of New England. Parker was then, and later, called the Hanging Judge. Some would say, Not hardly. A good man and a fine judge, in twenty-one years he tried a prodigious number of cases: more than 13,000. About 9,500 were convicted, and just 106 were sentenced to hang. Only 79 actually did.

The men who brought evildoers back for trial were at least as tough as the worst of their quarry. These included the three guardsmen, Heck Thomas, Bill Tilghman and Chris Madsen; big Bass Reeves, the first black deputy east of the Mississippi; Bud Ledbetter; and Frank Canton, who started as Texas cattle rustler and bank robber Joe Horner.

When the Muskogee (Creek) Nation was forced to abandon eastern tribal lands after 1826, the tiny settlement called Tulsey-Town was on the new tribal ground. Within a year, the Creek leaders had established a ceremonial town on a hill high above the Arkansas River, beneath a massive tree that still stands. Its called the Council Oak, and a second tree, still standing not far away, became a gallowsat least three rustlers died on it. For a time, the young town was a haven for outlaws, who, as one tale says, if they spotted no mount from their lookout on a nearby hill, boldly walked Tulsas streets, ate at its cafs and traded at its stores. Typical purchases included suspicious amounts of gunpowder and ammunition.

About the same time a Tulsa area murderer named Childers was ushered off this earth by Judge Parker, Tulsa had its first gunfight, a battle between city marshal Tom Stufflebeam and one Texas Jack, just one of a rich assortment of felons who haunted the area. Notable among them were Dick Glass, who sported a homemade bulletproof vest, and Wes Barnett, who tried to kill Creek chief L.C. Perryman and almost succeeded. It is said that Grat Dalton got into trouble in Tulsa shooting apples from citizens heads. Grat was drunk, of course, but that was nothing unusual for him. It was a tough town in a tough area. Somebody figured that between the Revolutionary War and the year 2000, over 40 percent of all U.S. deputy marshals who died in the line of duty were killed in what is now Oklahoma. And of course, outlaws who were that only in legend abound to this day. Take, for example, Annie McDoulet (or McDougal) and Jennie Stevensen (or Stevens), known to history as Cattle Annie and Little Britches, two teenage girls who supposedly were part of the notorious Bill Doolin gang. In fact, there is no documentation that Annie or Jennie engaged in anything more than minor thefts and bootlegging.

In contrast, the chapters to come chronicle the deeds and misdeeds of some of the worst outlaws in Oklahoma, plus a few of the truly inept, like bumbling Al Jennings. Al tried the owl hoot trail, was a miserable failure and spent some time in jail. He later became a politician, which some cynics would call a similar professiononly with clean sheets.

Four years after Judge Parker took his seat on the bench in Fort Smith, Tulsa got its very own post office, and in 1882, the grandly named St. Louis and San Francisco Railroadin common parlance, simply the Friscoarrived. The iron horse was critical to the survival of any frontier town, especially a settlement like Tulsa, which depended heavily on cattle. The next year, Fort Smith hanged its first malefactor, one John Childers. There would be plenty more, but as Robert Barr Smith tells us in the first chapter, Belle Starr wouldnt be one of them.

BELLE STARR

A LEGEND IN HER OWN MIND

Back before television, kids read books, played ball or went to the movies. Ah, the silver screen! Movies were cheapespecially if you were a kidand a big bag of popcorn cost only a nickel. Invariablyat least during Saturday matineesyou got to watch a double feature, plus an installment or two of Buck Rogers, a newsreel, the previews, one or two episodes of the Road Runner outwitting Wile E. Coyote, sometimes a travelogue and the ads for the local Chevy dealer and the plumber and whoever else your folks might need locally. You got a whole lot of entertainment for thirty cents, and you got to sit with your friends.