Contents

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

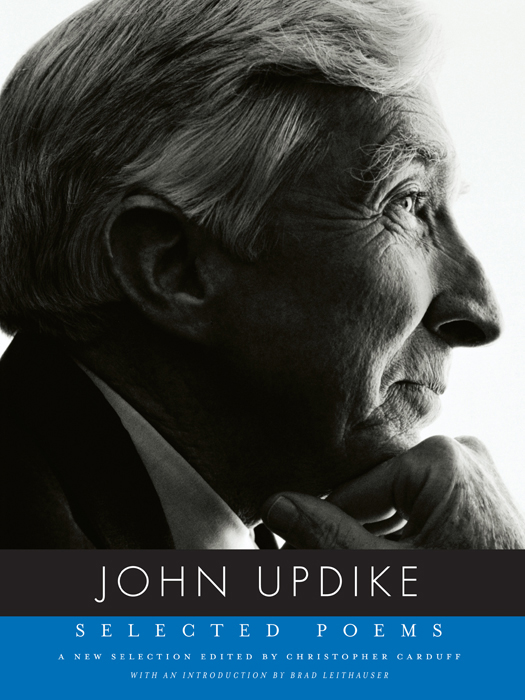

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF Copyright 2015 by John H. Updike Literary Trust. Introduction copyright 2015 by Brad Leithauser. All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A.

Knopf,

a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York,

and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada,

a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., Toronto. www.aaknopf.com/poetry Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC. Most of the poems here are from the following collections published by Alfred A. Knopf: Picked-Up Pieces, copyright 1975 by John Updike. Collected Poems19531993, copyright 1993 by John Updike. Endpoint and Other Poems, copyright 2009 by the Estate of John Updike. Higher Gossip, copyright 2011 by the Estate of John Updike. Higher Gossip, copyright 2011 by the Estate of John Updike.

Commuter Hop and Above What God Sees copyright 1971 by John Updike. Big Bard copyright 2001 by John Updike. Coming into New York copyright 2015 by John H. Updike Literary Trust. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Updike, John. [Poems.

Selections] Selected poems / John Updike; edited by Christopher Carduff;

introduction by Brad Leithauser.First edition. pages ; cm ISBN 9781101875223 (hardcover) I. Carduff, Christopher, editor. II. Title. PS 3571.

P 4 A 6 2015 813'.54dc23 2015022038 ISBN 9781101875230 (eBook) Cover design by Carol Devine Carson v4.1 a

Acknowledgments

Thirty-six of the poems printed here, and eleven of the seventeen parts of the poem titled Endpoint, first appeared in

The New Yorker. Others appeared in

The American Poetry Review,

The American Scholar,

Antus,

The Atlantic,

Bits,

Boston University Journal,

Bostonian,

The Christian Century,

Crazy Horse,

DoubleTake,

The Formalist,

The Georgia Review,

Grand Street,

Harpers,

The Harvard Bulletin,

The Harvard Lampoon,

Literary Imagination,

Michigan Quarterly Review,

New England Monthly,

The New Republic,

TheNew York Quarterly,

The New York Review of Books,

Ontario Review,

Oxford American,

The Paris Review,

Partisan Review,

Per Contra,

Poetry,

Saturday Review,

Scientific American,

Shenandoah,

The Southern California Anthology,

The Transatlantic Review,

Van Goghs Ear, and

The Yale Review. Shillington first appeared in

Fifty Years of Progress, 19081958: Shillington, Pennsylvania, a publication of Shillingtons Fiftieth Anniversary General Committee. The following presses first printed certain of these poems as broadsides or in limited-edition chapbooks: The Adams House and Lowell House Printers (Cambridge, Massachusetts), Limberlost Press (Boise, Idaho), The Literary Renaissance (Louisville, Kentucky), Lord John Press (Northridge, California), and Palmon Press (Winston-Salem, North Carolina).

Contents

Editors Note

This is a personal selection from the poetry that John Updike wrote between 1953, when he was twenty-one, and 2008, when he was seventy-six. The poems are ordered by date of completion, as determined by manuscript evidence gathered from the John Updike Papers at Harvards Houghton Library. The Index of Titles doubles as a ready reference for years of completion. Exact dates of composition and the publication history of each poem can be found in the Notes.

When Updike arranged the contents of his Collected Poems 19531993, he took pains to separate his poetry from his light verse, assigning the latter a secondary status and relegating it to a sort of appendix. If a set of lines brought back to me something I actually saw or felt, it was not light verse, he wrote in a preface. If it took its spark from language and stylized signifiersfrom a newspaper headline, say, or an exotic name or spellingit was. I have tried to honor this principle of segregation in making this selection, and to include only items that John Updike would have deemed poems. The contents are drawn not only from Collected Poems (1993), whose sheep-and-goats arrangement is unambiguous, but also from Americana (2001), Endpoint (2009), and other unsegregated sources. I have omitted not only light verse but also verse for children, poems in translation, found poems, and lines written for family birthdays and other private occasions.

I would like to thank Deborah Garrison of Knopf for inviting me to edit this book, and Brad Leithauser, William H. Pritchard, Martha Updike, and Geoff Wisner for helping me to choose its contents. If, however, the reader believes that a goat got through the gateor regrets that a favorite sheep is missing from the foldhe should lay the blame wholly on me. C.C.

Introduction

In one of John Updikes early stories, the narrator urges us to contemplate his dead grandmothers thimble. Moving through a dark house, heading downstairs, he upends a sewing basket left on the landing.

The moments dislocation encourages one of Updikes greatest strengths, his flair for simile and metaphor. Retrieving the thimble from the floor, briefly uncertain what it is, he describes it as a stemless chalice of silver weighing a fraction of an ounce. The metaphors religious overtones are brightly suited to his succeeding sensations: The valves of time parted, and after an interval of years my grandmother was upon me again, and it seemed incumbent upon me, necessary and holy, to tell how once there had been a woman who now was no more, how she had been born and lived in a world that had ceased to exist. He is inviting us to partake in one of literatures mystical ritesto drink deep and slake our souls from a chalice smaller, lighter than a tulip. Updike was still in his twenties when he wrote these words, which appear in a story that bore, I suppose, the lengthiest title of any piece of fiction he ever published: The Blessed Man of Boston, My Grandmothers Thimble, and Fanning Island. The young writer had already received, or was soon to receive, a host of propitious honors: a summa cum laude undergraduate degree from Harvard; employment at The New Yorker; book publication in three different genres (novel, poetry, short stories); and a widespread critical recognition that hed already become, and promised long to be, a decisive shaper of contemporary American literature.

By contrast, the woman whose lifes lineaments he was urging on his readers was a figure of little worldly consequence: elderly, insular, and infirm. She was sketched closely from life, and the fictional thimble was an actual thimble. She was Katherine Ziemer Kramer Hoyer, Updikes maternal grandmother, with whomalong with his mother, his father, and his grandfatherhe lived throughout his childhood, much of it in a century-old farmhouse in Plowville, Pennsylvania, outside Reading. Though finan cially strapped, it was a richly populous household for the rearing of an only child. It was also what might be called the House of His Life; though Updike wrote lovingly and knowingly about various homes and buildings throughout his career, this sandstone farmhouse (bought at his mothers insistence, over the objections of her husband and her son, who resented its isolation) became his souls dwelling place. Theres something touching in the distance between the blazing young man, so clearly bound for international fame, and the obscure woman who never to my knowledge went outside the boundaries of Pennsylvania, who had no possessions, who never attended a movie, and whom he never saw reading a book.