Contents

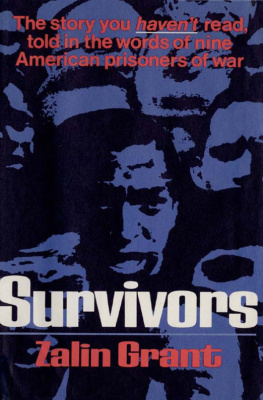

Survivors

Zalin Grant

This book may well be the most unusual document to come out of the Viet Nam war. It is the moving story of nine American soldiers and pilots who were captured and held prisoner for five years. It could only be told in their own words; and so author Zalin Grant interviewed each of the nine men, and edited and wove their accounts together to form a single, compelling narrative of war and survival.

For three years these Americans were held in a Viet Cong jungle prison, where they struggled against starvationand themselves. They describe the details of their daily existence as the war ebbed and flowed around them: the rats, the terror of American bombing raids, the sickness. Through juxtaposition of their individual stories we see the subtle, destructive tensions that operate on a group of men in such desperate circumstances.

Then they were marched up the Ho Chi Minh trail to Hanoi, where their physical ordeal gave way to an agonizing moral dilemma. Should they join the Peace Committee, a group of POWs protesting the war? Or should they resist their captors by all possible means as ordered by the secret American commander of the Hanoi prison? After three years in the jungle on the edge of survival, each man had to answer the questions: Who am I? What do I believe?

These nine men form a cross section of the army we sent to Viet Nam. Their words illuminate not only their individual background and experience, but also the meaning of this war for all of us.

Copyright 1975 by Claude Rene Boutillon

First Edition

All Rights Reserved

Published simultaneously in Canada

by George J. McLeod Limited, Toronto

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title:

Survivors.

1. Vietnamese Conflict, 1961Prisoners and prisons, North Vietnamese. 2. Vietnamese Conflict, 1961Personal narratives, American. I. Grant, Zalin.

DS559.4.S9 1975 959.70437 7517637

ISBN 0-393-08727-1

ISBN 978-0-393-24250-8 (e-book)

to Claude

SURVIVORS

SURVIVORS

FRANK ANTON, 24, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Pilot.

Captured January 5, 1968, near Happy Valley.

DAVID HARKER, 22, Lynchburg, Virginia. Rifleman.

Captured January 8, 1968, Happy Valley.

JIM STRICTLAND, 20, Dunn, North Carolina. Rifleman.

Captured January 8, 1968, Happy Valley.

WILLIE WATKINS, 20, Sumter, South Carolina. Grenadier.

Captured January 9, 1968, Happy Valley.

JAMES DALY, 20, Brooklyn, New York. Rifleman.

Captured January 9, 1968, Happy Valley.

ISAIAH (IKE) McMILLAN, 20, Gretna, Florida. Mortarman.

Captured March 12, 1968, Happy Valley.

TOM DAVIS, 20, Eufaula, Alabama. Mortarman.

Captured March 12, 1968, Happy Valley.

JOHN YOUNG, 22, Chicago, Illinois. Special Forces.

Captured January 30, 1968, near Khe Sanh.

TED GUY, 38, Elmhurst, Illinois. Pilot.

Captured March 11, 1968, in Laos.

The radio message came at 7:01 Friday evening as I was writing a school classmate to tell her I would be home in two months. A battalion commander asked brigade to send a couple of gunships to assist a rifle company under small-arms and mortar attack southwest of Happy Valley. There was nothing unusual about the request. Id answered dozens of a similar urgency during my tour. This time, though, I felt a little uneasy when the word first came down from the tactical-operations center. I thought maybe it was because Id just gotten back two days earlier from a Bangkok R n R. I knew of cases where pilots took a week off, dulled their reflexes, and made mistakes when they returned. My copilot, who was new in-country, had done the flying all day. To become an aircraft commander it was necessary to be checked out by the old hands in the platoon; and I was the only one he hadnt flown with. I dreaded night flying, especially on a rainy night. But I decided I had better take over. When we reached the helicopter, I slid into the right-hand seat.

On the way to the valley we were shot at by a 50 caliber. The tracers looked like reddish-yellow baseballs coming up at us. The North Vietnamese had green tracers which I dont think they liked to use because we immediately knew it was them. The reddish-yellows we might confuse for friendly ricochets. I turned off my running lights and asked Lead if he wanted me to try to get the gun. Negative, he radioed. Lets see what C Companys got out there.

Charlie Companys commander had been killed. The artillery forward observer, a lieutenant, was on the radio. My unit has been overrun, he said as we made contact. I could tell from the pitch of his voice that he was very scared. They were being hit by mortarswe could see the muzzle flashes. Friendly 105-mm howitzers were firing close-in support from a nearby hill. Lead radioed the lieutenant to shut off the howitzers so we could get the enemy mortars. We didnt want to get knocked out of the air by our own artillery.

Firebird, this is Goblin, the lieutenant replied. Negative. Repeat, negative. We may be attacked again. Ill keep it going a few more minutes. Then Ill turn it off and you can come down and get them.

We pulled off to the south and orbited over the river. We drew small-arms fire and climbed higher. Forty minutes passed. It was getting darker. We were running low on fuel. Loaded with ammo we were good for about an hour and three quarters. It was fifteen minutes out and fifteen minutes back to brigade headquarters. That meant we had committed all but thirty-five minutes of our flying time. The battalion commander was on a hill several miles from Charlie Company. The radio frequency was busy with requests for flare ships, more artillery, and ground reinforcements.

Finally Lead called the lieutenant. Goblin, Goblin, this is Firebird. Look, were running low on fuel. If you want to use us youll have to do it fast.

Firebird, this is Goblin. Roger that. Wait one.

The artillery stopped abruptly. The lieutenant called us down. Two red flares were to mark the edges of the companys perimeter and we were to hit outside the lights. We rolled in. Lead saw both flares but I could get a fix on only one. I ordered my crew not to fire. No help to blast our own troops. Lead made his pass through the area and broke right. As I followed I received quite a bit of ground fire, judging from the flashes. Just as I turned I heard a loud Wham! and the ship lurched to the left.

I glanced at the Christmas tree, the console between the copilot and me. If anything goes wrong, the bank of lights flash on. I thought we had taken a bad hit, but no indicators were showing. I radioed Lead that I had to return to the base. He said, I want to get those bastards, and wheeled to make another pass. A wingmans job is to follow his team leader. I followed but I didnt intend to go low enough to use my rockets. He rolled in, worked his machine guns and rockets, and broke right again. As I turned out behind him, my hydraulic warning lights flickered on. I smelled the heavy odor of leaking fluid. Without hydraulics a helicopter maneuvers like a ten-ton truck.

My controls were freezing, and as I began a slow turn to the right the whole world opened up. I would say two hundred soldiers with AKs and three machine guns were working us over. In thirty seconds we took thirty hits. I made a mistake by trying to turn left to get out of the fire. This took me west toward Laos, and the sky was filled with tracers. We were not returning the fire. My door gunners weapons had jammed. In our unit some door gunners guns never jammed and somes always jammed. Lewis, my crew chief, had the reputation of a jammer. Pfister, the other door gunner, was flying with me for the first time.

Next page