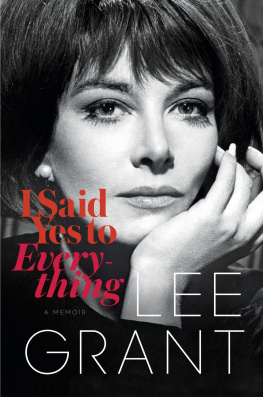

My Family

M y mothers job was to mold me into her American Dream.

Didnt young Witia from Odessa expose the child in her belly to every art museum in New York City, every day that she could carry me on her long legs? The magic of transformation was real in her young life. The Jewish child hunted in her cellar by goyim on horseback was transplanted to a new land where anything was possible, if you made it happen. And she wanted to make it happen for her daughter.

Witia was determined to plunge her hands into my baby fat and model me into a superior, beautiful being, who would either marry rich or rise above all others in the arts: ballet, theater.

There was no question about it.

M y father was born in the Bronx, the youngest son of Polish Orthodox Jewish immigrants. His brother and sisters were ambitious. His brother, Aaron, and sister Anne were show business lawyers.

My father, Abraham, was the good son, the good man. He graduated from Columbia, where he had studied economics with John Dewey and was on the wrestling team. He kept a neat, tight, muscular body all his life. He bent his head over the radio every Saturday afternoon to listen to the Metropolitan Opera. He loved coloraturas. My father was the director of the Young Mens and Young Womens Hebrew Association of the Bronx. It was a position of great responsibility, great dignity. He was the moral compass of the family.

My grandfather went to shul every day. His tiny wife, Ida, kept an Orthodox home. They lived in a clean, old apartment on College Avenue in the Bronx. Their children must have supported them, because my grandfather never left the shul for his hardware store. But they and America raised smart, goal-oriented children.

The story goes that my mother went to the Bronx Y to get a job giving classes in dance. She had just graduated from college, where she majored in movement in the Isadora Duncan tradition. I have pictures of her from school. She was beautifulfive feet seven, straight back, long shining dark hair, hazel eyes. When she smiled, her top and bottom teeth glistened like a Spanish dancers.

She sat in the chair in my fathers office, reciting her qualifications for the job. She was rocking in the chair, nonchalant, when she did one rock too many. The chair tipped over and she landed on the floor. My father came from behind his desk, laughing, and helped up my flustered, embarrassed mother. And that. Was that.

My mothers name was Witia Haskell, Americanized from Vitya Haskelovich. Her mother, Dora, had five childrenthree boys, Joseph, Raymond, and Jack, and two girls, Witia and Fremo. I never knew my grandfather Leon, for whom I was named. He was a clothing designer and a committed Zionist who left for Palestine with several other Zionist men before I was born. He must have done well, because he bought the brownstone on 148th and Riverside Drive before he returned to Palestine to establish a Jewish state.

They all died of malaria while fighting for their cause. There is a plaque in Rishon LeZion with his name on it. In Russian Leon is Lyov, as in Lyov Tolstoy, Leo Tolstoy. My name is Lyova. There is no such name in Russian. Try being a Lyova in a world of Bettys and Judys and Emilys and Janes.

Position your tongue for an L, then say yaw, then vah. In high school I changed the V to an R and Lyora, pronounced Leora, was born. Hence Lee.

From the time I can remember remembering, I was my mothers beloved thing, little girl, petted, brushed, combed, bathed, fed, beautiful, lived through. Her life. Her lovely sweet breath. The light in her hazel eyes.