A Genuine Barnacle Book

A Barnacle Book | Rare Bird Books

453 South Spring Street, Suite 302

Los Angeles, CA 90013

rarebirdbooks.com

Copyright 2018 by Stephen Jay Schwartz

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever, including but not limited to print, audio, and electronic. For more information, address:

A Barnacle Book | Rare Bird Books Subsidiary Rights Department,

453 South Spring Street, Suite 302,

Los Angeles, CA 90013.

Set in Dante

epub isbn : 9781644280225

Publishers Cataloging-in-Publication data

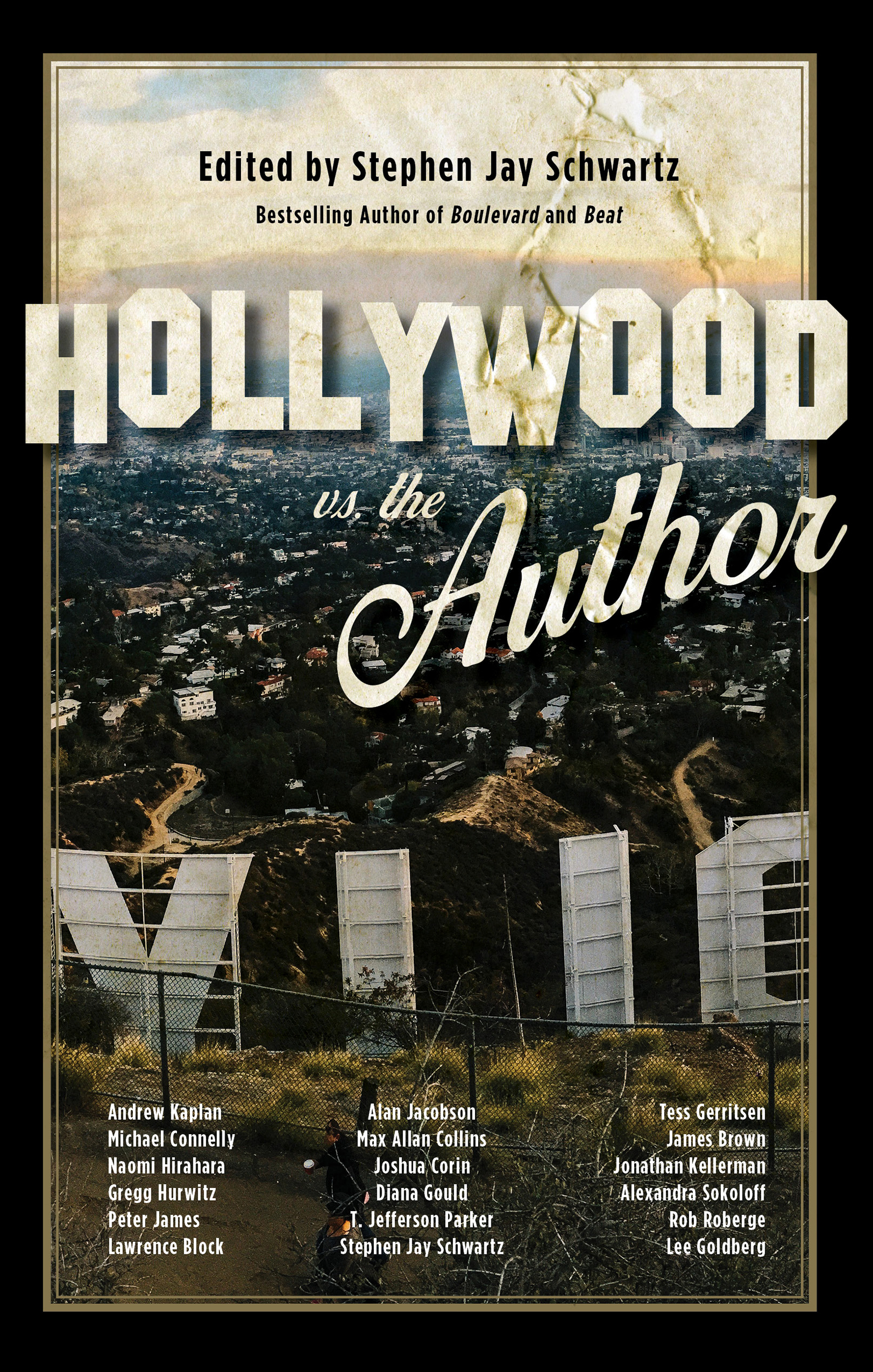

Names: Schwartz, Stephen Jay, editor.

Title: Hollywood vs. The Author / edited by Stephen Jay Schwartz.

Description: Includes bibliographical references. | First Trade Paperback Original Edition | A Barnacle Book | New York, NY; Los Angeles, CA:

Rare Bird Books, 2018.

Identifiers: ISBN: 9781945572869

Subjects: LCSH Motion picture authorship. | Motion picturesPlots, themes, etc. | FictionFilm and video adaptations. | Motion pictures and literature. | Film adaptations. | BISAC LANGUAGE ARTS & DISCIPLINES / Authorship | PERFORMING ARTS / Film / Screenwriting

Classifications: LCC PN1997.85 .H65 2018 | DDC 791.43/6dc23

For the authors who have published and

for the authors who have yet to publish.

For the authors who have sold their screen rights and

for the authors who have yet to sell their screen rights.

Hold your heads high, for you are the storytellers.

Stand strong, and prepare for battle.

Contents

Introduction

by Stephen Jay Schwatrz

I n the beginning there was story. Told around the campfire, passed down from one generation to the next. At times the story was spoken; at times it was sung. But voices alone werent enough, so the stories became drawings on the walls of caves or woven into the fabric of ceremonial shawls or etched onto the surfaces of clay pots. Eventually the stories became words written on parchment, then typed onto paper, then immortalized onto the pages of the modern novel.

In another beginning there was a pinprick of light shown through a piece of paper. The light captured an upside-down image onto a silver plate. A lens was invented to upright the image, and a shutter was installed to separate the image into individual frames that created a sense of seamless motion onto a silver screen.

Two brothers named Lumiere got to work and, using something they called the Cinematographe, recorded common-day images of families and trains and friends playing cards. The images shocked an audience who had never seen photographs in motion. While these early films were revolutionary, they didnt seem capable of replacing the experience people had reading novels or watching plays. Movies were still a fad, a gimmick, incapable of telling stories in an intellectually satisfying way.

Early filmmakers sensed that the power of film rested in its ability to tell a story in ways never before imagined. Instead of observing a static play from the center of a theater, the camera allowed the audience to enter the story. The first close-up shots produced a sense of unease for moviegoersthe audience simply wasnt used to the sight of giant disembodied body parts. One early film financier is said to have exclaimed, I paid for the whole person, I want to see the whole person! But an audience eager to be entertained adapted to the language of film, and soon close-ups, medium and long shots, and zoom and tracking shots became the expected way of telling stories on film. Add to that the invention of film editing and the experience of watching movies rivaled anything that could be experienced in the theater or in a novel.

If stories were to be told using this new medium of film, then a new kind of writer would be needed. The writers job would be to describe images that would be seen on the screen, with sparse dialogue written on placards placed intermittingly between the pictures. The writers skill set required him or her to turn words into images, dialogue, and camera shots. Not a novelist or playwright, but a screenwriter.

Except for a handful of early directors, most notably F. W. Murnau and Abel Gance, films were not seen as art. In America, in particular, they were considered escapist entertainment for the masses, like vaudeville. The physical humor of Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd kept the world laughing, bringing nickels into the movie houses and financing the growth of the industry. Charlie Chaplin combined comedy with pathos by inventing his famed character the Tramp. This initiated a trend toward heartwarming, empathetic stories revealing the kind of character development more commonly seen in plays or novels.

Despite classic silent era films such as Pandoras Box, Sunrise, The Last Laugh, and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligary , motion pictures really came of age with the advent of the Talkies. No longer was dialogue relegated to the occasional placard inserted between dramatic action shots. The medium had found its voice and was suddenly capable of transmitting complex, dramatic messages to a large, mainstream audience.

And yet the film industry, now centered in the fantastical land of Hollywood, California, was viewed with contempt by East Coast critics who held theater and literature as truer forms of art. The new West Coast movie mogulsAdolf Zukor (created Paramount Pictures), Samuel Goldwyn and Louis B. Mayer (Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer), David O. Selznick (who would produce Gone with the Wind ), Walt Disney, Harry and Jack Cohn (Columbia Pictures), Jack Warner (Warner Bros.), Daryl F. Zanuck (20th Century Fox), and Carl Laemmle (Universal Pictures) wanted the kind of prestige bestowed upon Broadway plays and Pulitzer Prizewinning novels. They felt that the motion picture industry deserved similar accolades. Baiting their hooks with the prospect of fortune and fame, they set out to woo the greatest novelists and playwrights of their day.

And they hooked a few. William Faulkner. Nathanael West. James M. Cain. Raymond Chandler. F. Scott Fitzgerald. John Steinbeck. Bertolt Brecht. Anita Loos. Ben Hecht. More modern writers include Joan Didion, James Baldwin, Truman Capote, Ruth Prawer Jabvhala, and Patricia Highsmith. All were authors or playwrights of great esteem lured to Hollywood by promises of weekly salaries often rivaling the total payouts of their bestselling novels. Many of these authors soon learned that writing for the movies was vastly different from writing novels. Many, like Faulkner, admitted they were terrible adapters of novels. They did their time in Hollywood for the cash and retreated back to the comfort of writing books when their coffers were full. Others got the hang of it, realizing that novels and films were entirely different creatures. The ones who succeeded at writing both novels and screenplays understood that a four-hundred-page novel could never be faithfully translated into a one-hundred-twenty-page film. The film exchanged words for images. Three pages of description in a novel could be captured in a single image on film. Even dialogue became image, and the crafty screenwriter learned to take the content of a long soliloquy and turn it into a few choice bits of dialogue separated by images that reinforced the message of those words.

Not all authors could make the switch, and not all authors wanted to. While working with film director Billy Wilder to adapt James M. Cains novel Double Indemnity , fellow author (then screenwriter) Raymond Chandler had this to say about what he considered an agonizing time in Hollywood: Too many people have too much to say about a writers work. It ceases to be his own. And after a while, he ceases to care about it. He has brief enthusiasms, but they are destroyed before they can flower, ( Writers in Hollywood 19151951 by Ian Hamilton).