Hull Akasha Gloria. - But Some of Us Are Brave

Here you can read online Hull Akasha Gloria. - But Some of Us Are Brave full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Lightning Source Inc. (Tier 3), genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

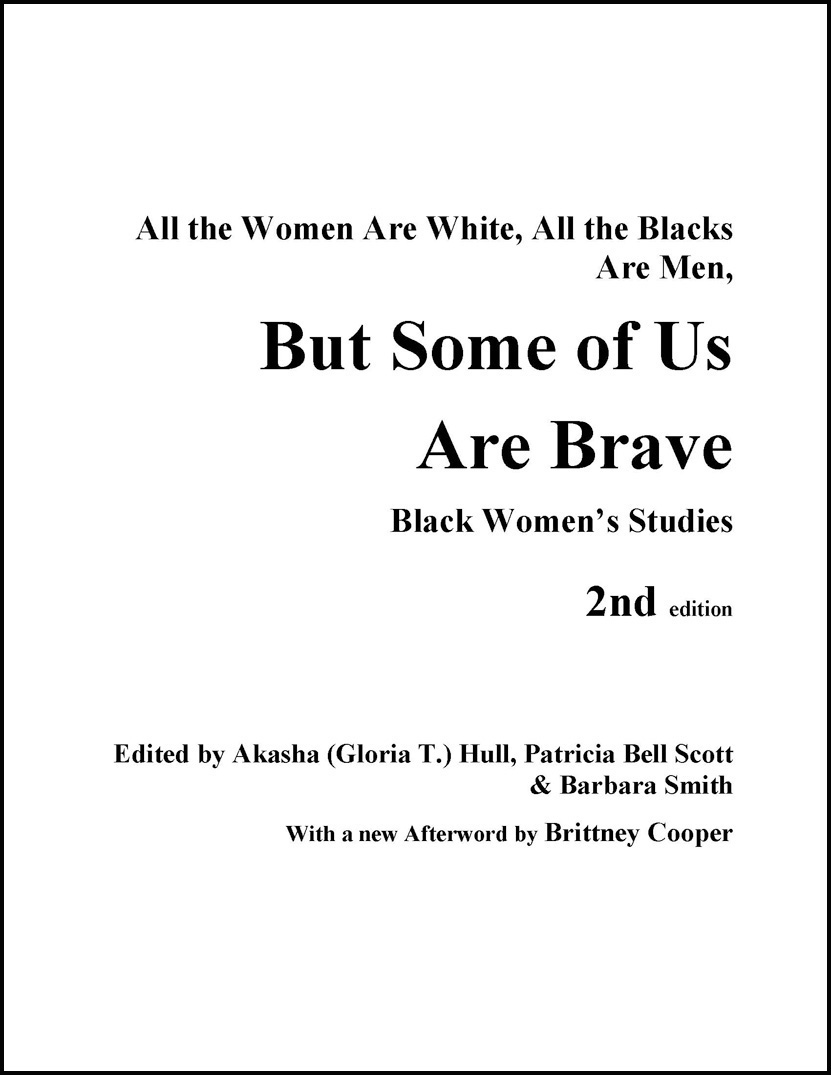

- Book:But Some of Us Are Brave

- Author:

- Publisher:Lightning Source Inc. (Tier 3)

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

But Some of Us Are Brave: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "But Some of Us Are Brave" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

But Some of Us Are Brave — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "But Some of Us Are Brave" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

But Some of Us

Are Brave

Compilation and introduction copyright 1982 by The Feminist Press and Akasha (Gloria T.) Hull, Patricia Bell Scott, and Barbara Smith. All rights reserved.

Afterword copyright 2015 by Brittney Cooper

Copyright information on individual pieces can be found on pages 39597; these pages constitute a continuation of the copyright page.

Published by the Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 365 Fifth Avenue, Suite 5406, New York, NY 10016

Second Edition

This work was developed under a grant from the Womens Educational Equity Act Program, U.S. Department of Education. However, the content does not necessarily reflect the position of that Agency, and no official endorsement of these materials should be inferred.

We gratefully acknowledge the Muskiwinni Foundation of New York, N.Y., for a grant which aided in the development and publication of this work, and we offer special thanks to the Polaroid Foundation and to Mary Anne Ferguson for their contributions toward the publication of this work.

eISBN: 978-155861-899-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this title.

Cover photo: French Collection. Library of Congress.

For Beverly Towns Williams whose commitment and generosity helped make this book possible.

Table of Contents

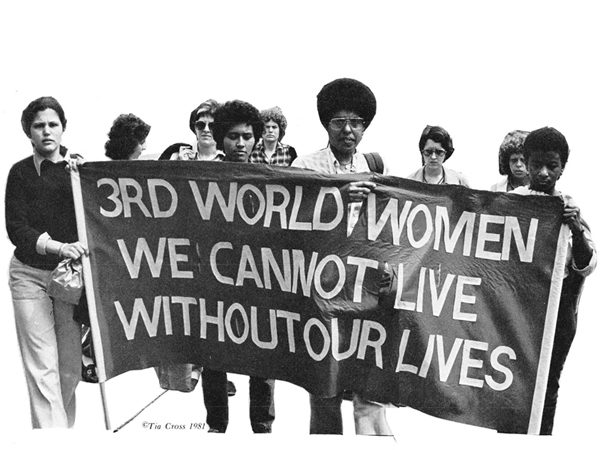

Photo by F.B. Johnston

Woman Seated at Tuskegee Institute, 1906.

Contents

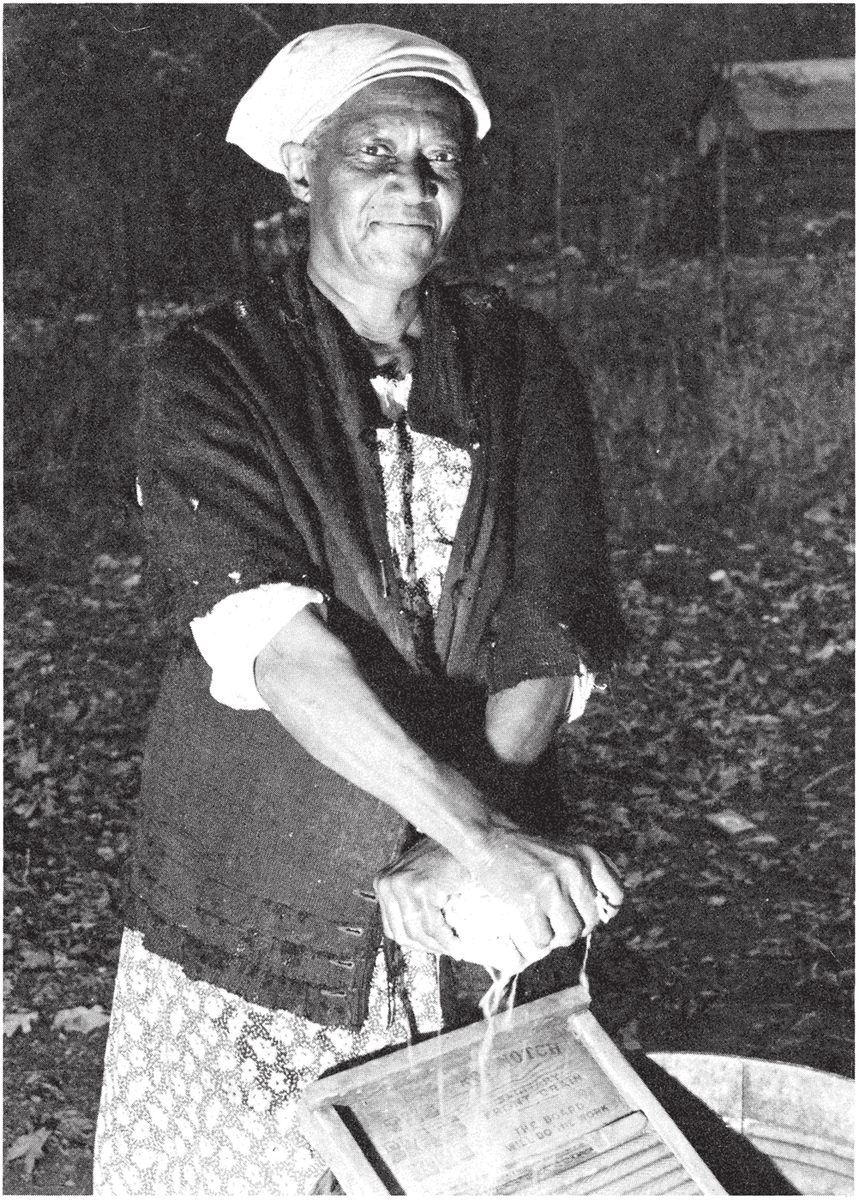

Photo by Arthur Rothstein

Evicted sharecropper, Butler County, Missouri; November 1939.

They were women then

My mamas generation

Husky of voiceStout of

Step

With fists as well as

Hands

How they battered down

Doors

And ironed

Starched white

Shirts

How they led

Armies

Headragged Generals

Across mined

Fields

Booby-trapped

Kitchens

To discover books

Desks

A place for us

How they knew what we

Must know

Without knowing a page

Of it

Themselves.

Alice Walker

MARY BERRY

Hull, Scott, and Smith have put together a volume that very much needed doing. The education of students has been long bereft of adequate attention to the experiences and contributions of Blacks and women to American life. But practically no attention has been given to the distinct experiences of Black women in the education provided in our colleges and universities. This absence of attention is molded and reflected in the materials made available by scholars.

Black historians and others who focus on Afro-American history are little better than other scholars on this issue. Without the pioneering work of Gerda Lerner and such younger scholars as Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, little would be available in print to begin the quest for knowledge concerning Black womens experiences.

Unfortunately, it is also true that womens studies, which has had to exist on the periphery of academic life, like Black studies, has not focused on Black women. The womens movement and its scholars have been concerned, in the main, with white women, their needs and concerns. However, there are exceptions. For example, in Jo Freemans Women: A Feminist Perspective, two extended essays are devoted to the particular condition of Black women. The feminist perspective, according to Freeman, looks at the many similarities between the sexes and concludes that women and men have equal potential for individual development. Differences in the realization of that potential, therefore, must result from externally imposed restraints, from the influence of social institutions, and values. The essay she includes by Pauline Terrelonge Stone, Feminist Consciousness and Black Women, describes the Black womans condition as differentiated from white womens, in the peculiar way in which the racial and sexual caste systems have interfaced. Black women, according to Stone, have suffered from double dependency on their mates and employers. They have been expected to work while white women have been expected not to. Sexism, however, consigns Black women to lower status jobs, to female occupations such as nursing and teaching. She believes a feminist consciousness would help Blacks to understand that many social problems affecting Blacks are in part at least attributable to the operation of sexism in our society. Black women need to understand that sexism and racism impinge on their opportunities negatively.

Hull, Scott, and Smith and their contributors would agree with Stones analysis as they state that a feminist, pro-woman perspective is necessary to understand fully the experiences of Black women in society. However, more importantly, perhaps Black womens studies will help Black women and men understand more about the way in which the Black community is oppressed.

Notes

For example, Anne Firor Scott in her introduction to the modern edition of Julia Cherry Spruills Womens Life and Work in the Southern Colonies (New York: W.W. Norton Co., 1972), does not note that the book is about white women. William Chafe in The American Woman: Her Changing Social, Economic and Political Roles, 1920-1970 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972) mentions Negroes twice. Both books, despite their titles, are not about American women but American white women.

For example, the leading history, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of Negro Americans (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1974) by John Hope Franklin pays no specific attention to Black womens roles.

Jo Freeman, Women: A Feminist Perspective (Palo Alto, Ca.: Mayfield Publishing Co., 1979), pp. xxi, 575-588.

GLORIA T. HULL and BARBARA SMITH

Merely to use the term Black womens studies is an act charged with political significance. At the very least, the combining of these words to name a discipline means taking the stance that Black women existand exist positivelya stance that is in direct opposition to most of what passes for culture and thought on the North American continent. To use the term and to act on it in a white-male world is an act of political courage.

Like any politically disenfranchised group, Black women could not exist consciously until we began to name ourselves. The growth of Black womens studies is an essential aspect of that process of naming. The very fact that Black womens studies describes something that is really happening, a burgeoning field of study, indicates that there are political changes afoot which have made possible that growth. To examine the politics of Black womens studies means to consider not only what it is, but why it is and what it can be. Politics is used here in its widest sense to mean any situation/relationship of differential power between groups or individuals.

Four issues seem important for a consideration of the politics of Black womens studies: (1) the general political situation of Afro-American women and the bearing this has had upon the implementation of Black womens studies; (2) the relationship of Black womens studies to Black feminist politics and the Black feminist movement; (3) the necessity for Black womens studies to be feminist, radical, and analytical; and (4) the need for teachers of Black womens studies to be aware of our problematic political positions in the academy and of the potentially antagonistic conditions under which we must work.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «But Some of Us Are Brave»

Look at similar books to But Some of Us Are Brave. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book But Some of Us Are Brave and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.