Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Ileene Smith

I honor beginnings. Of all things, I honor beginnings. I believe that what was has always been, and what is has always been, and what will be has always been.

Louis Kahn

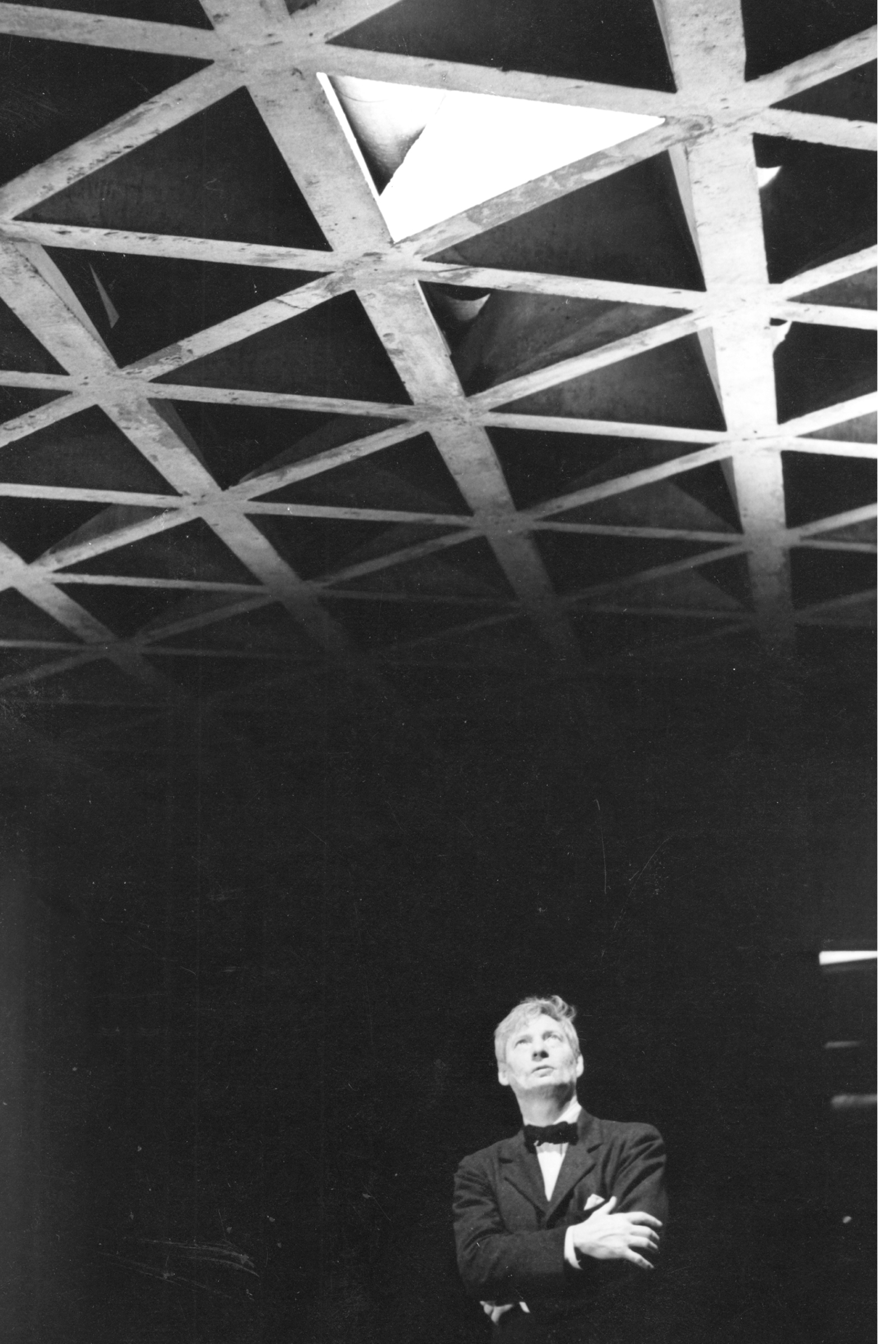

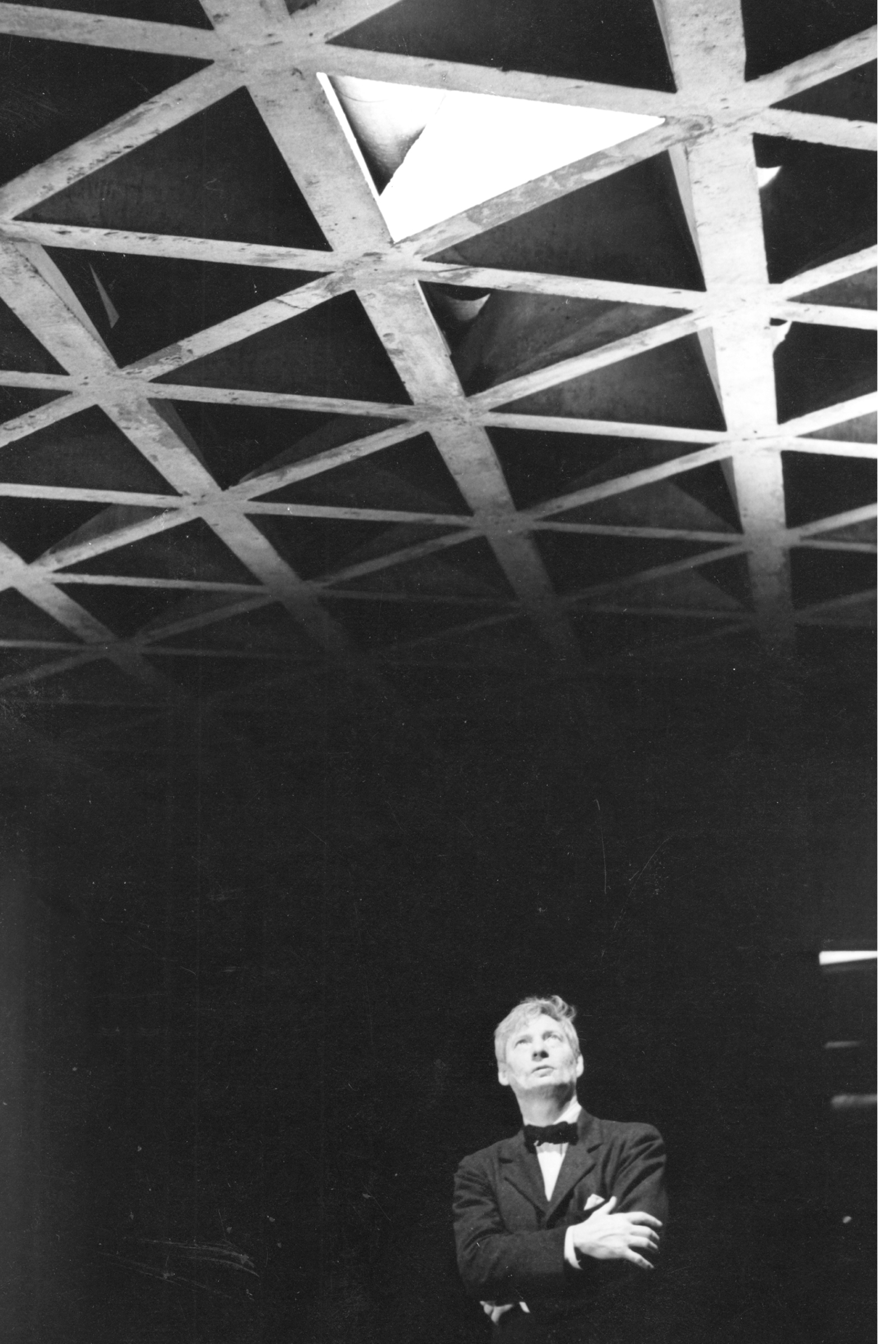

There was much to praise in his work, his colleagues felt, and they would not have hesitated to call him one of the greatest architects of the twentieth century. Just about everybody in the profession, across a broad range of architectural schools and styles, admired what he did. They thought of him as the artist among them. His output over the course of a lifetime was small, but his best buildings were uniquely his, and they were beautiful in a surprising new way.

If he inspired any feelings of envy, they were rare and strangely muted. Perhaps that was because he was such a bad businessman, so hopeless at the financial side of the practice that no one worried about having to compete with him. Or perhaps it was his soft, disarming manner. Through some combination of his poverty-stricken childhood, his unsuccessful school days, and his generally unprepossessing appearance, he had acquired a personality that was completely unthreatening. Even among people who knew how good his work was, the character he radiated was affable, conciliatory, and a bit self-mocking.

Louis Kahn was a warm, captivating man, beloved by students, colleagues, and friends, enduringly attractive to strangers and intimates alike. But he was also a secretive man hiding under a series of masks. There was the physical mask he wore permanently on his face, a layer of heavy scars produced by a childhood accident. Then there was the mask of conventionality he wore in his private lifethe forty-four-year marriage to Esther Kahn, mother of his oldest daughter and partner in his Philadelphia social lifewhich covered over his intense romantic liaisons with two other women, Anne Tyng and Harriet Pattison, each of whom bore him a child outside of wedlock. There was also his name, which was not really his name at all, but a convenient invention devised by Kahns father and subsequently imposed on his whole family when they immigrated to America. The boy who had been born Leiser-Itze Schmulowsky in Estonia became Louis Isadore Kahn in America: not an escape from Jewish identity itself, but a purposeful elevation from the lowly Eastern European category to the more respectable and established ranks of German Jews. And even Jewishness, for Kahn, may have been another kind of mask, defining him in the eyes of WASP Philadelphia, not to mention the echt-Protestant architecture world, but less fully defining him to himself. If he received more commissions to build synagogues than churches or mosques, it is nonetheless the case that among his built masterpieces only a mosque (in Dhakas Parliament Building) and a church (First Unitarian in Rochester) emerged triumphant; the synagogues, for the most part, foundered in the design phase. Im too religious to be religious, he once told a friend, after a major Philadelphia synagogue commission had disappointingly died on the drafting board following years of conflict with, and within, the congregation.

Perhaps he also meant that his sole religion was architecture. This was what everyone who knew him sensed about him. His wife, his lovers, and his three childrenSue Ann, Alexandra, and Nathanielcame to understand sooner or later that his work was his one great love. His fellow architects often voiced their respect for his tremendous integrity, repeatedly noting (perhaps with a combination of schadenfreude and chagrin) the way he emphasized the artistic side of the profession over the business side. Even his clients, who sometimes wanted to tear their hair out at his refusal to let a project out of his hands, perceived that his constant revisions resulted from a deep-seated perfectionism, not just orneriness or bad judgment.

His father had wanted him to be a painter, and his mother had wanted him to be a musician. They saw these talents in him as a child, and these remained important aspects of himself that he was to cultivate all his life. But even his parents recognized that once he had discovered architecture, there was no turning back. It became his life. It would not be quite accurate to say it was a life he never regretted, for even to contemplate regret implies the awareness of a path not taken, and for Louis Kahn there was no other path. He had always been meant to be an architect, or so he believed, and such convictions were at the core of his way of thinking. You say to brick, What do you want, brick? Kahn remarked in one of his famously gnomic talks. Brick says to you, I like an arch. If you say to brick, Arches are expensive, and I can use a concrete lintel over an opening. What do you think of that, brick? Brick says, I like an arch. For Kahn, there was no going against the inherent nature of the materialsand that included himself.

This is not to say that Louis Kahn was the kind of egotistical, overbearing, power-mad architect routinely handed to us by fiction and drama, in characters like Ibsens manipulative Halvard Solness or Ayn Rands appalling Howard Roark. The authors of such imaginary architects may nervously disown them, as Ibsen tries to do, or jealously adore them, in Rands heavy-handed mode, but either way this character is always a galvanizing central figure who wields tremendous force in his own realm. He doesnt just control the physical environment other people inhabit. He also seems to control the people themselves. Women are violently attracted to him, and he exploits this to the full. He is the master of all fates, his own and others, and whether things turn out well or badly for him, he is viewed by both his author and himself as the prime mover in his life.

That caricature does not describe Louis Kahn. (Perhaps it does not describe anybody, including Baron Haussmann and Albert Speer: reality, even at its most grotesque, rarely lives up to the overheated imaginings of writers.) If Kahn was an egotist, it was of a very different sort. He was a generous egotist, who wanted others to get as much pleasure out of life and work as he did. He was a communally minded egotist, who depended heavily on his collaborators and made them feel the value of their contribution, whether it was a single visual element or the knowledge of a specific building material. He was an egotist who supported and inspired the careers of his students. He was the kind of egotist who saw and acknowledged the corresponding ego in every other living thing, and even in some thingslike brickthat were not living. Perhaps, in the normal sense of the word, he was not an egotist at all, except in the way children are. But he certainly knew his own worth, he trusted his own instincts, and he was, in his own way, ruthless. It was these qualities that allowed him, in the face of the enormous opposition that life puts up against new ideas, to produce his architectural wonders.

An architect is a strange kind of artist. Compared to a painter or a writer, he stands at a rather distant remove from his finished work. The course of his artistic project, the shape of its ultimate outcome, even whether there will be an ultimate outcome are all subject to factors far beyond his control. Money is one of these factors; so are client tastes. Local climate conditions, building regulations, and availability of materials will also come into play. Even historypolitical or religious or cultural developments about which the architect has no say and possibly even no knowledgecan interfere with his project, and the larger the project, the more likely this is to happen.