Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

Guide

For my parents, Freda and Steve Jarmulowski, with love and appreciation

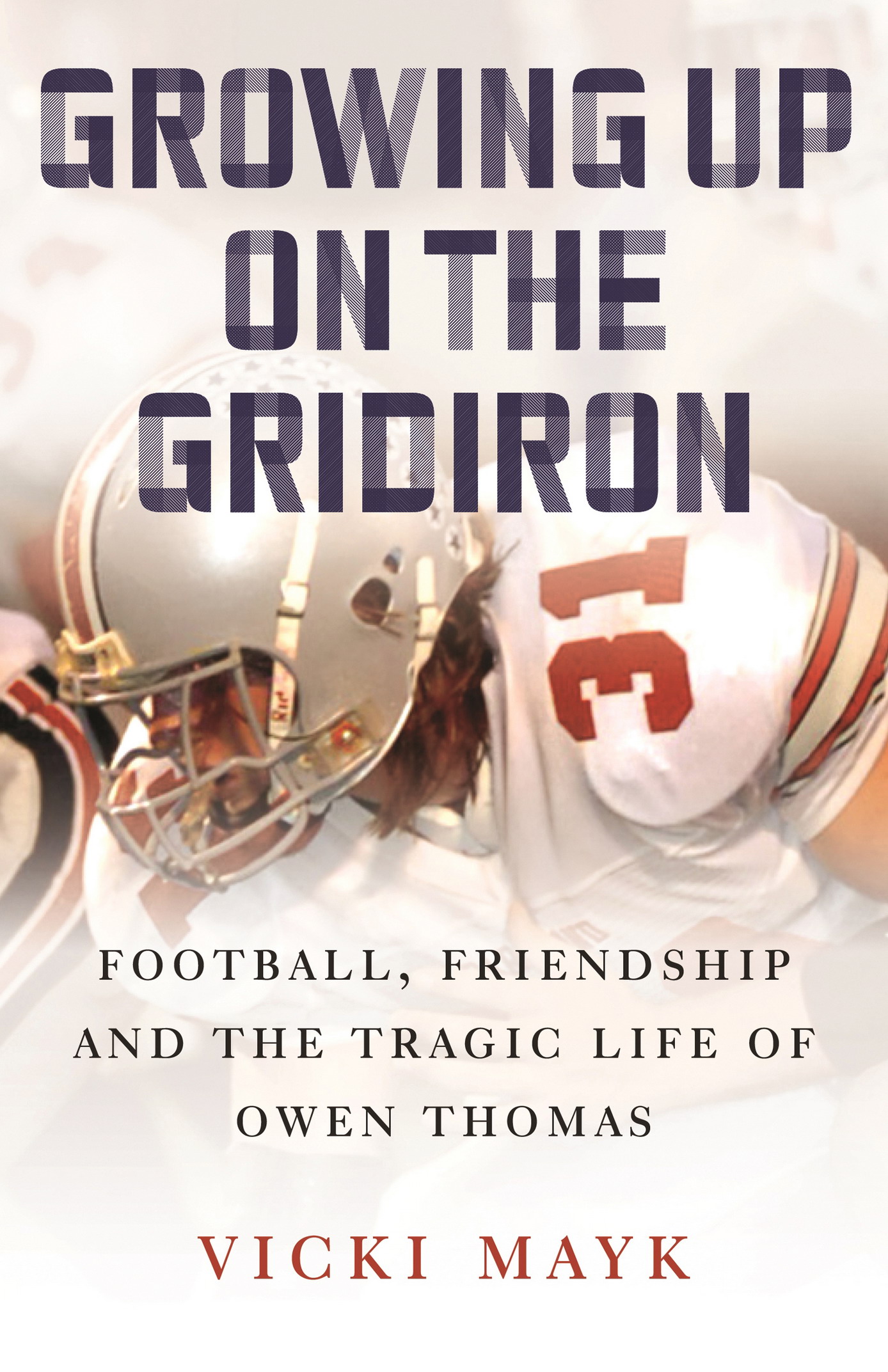

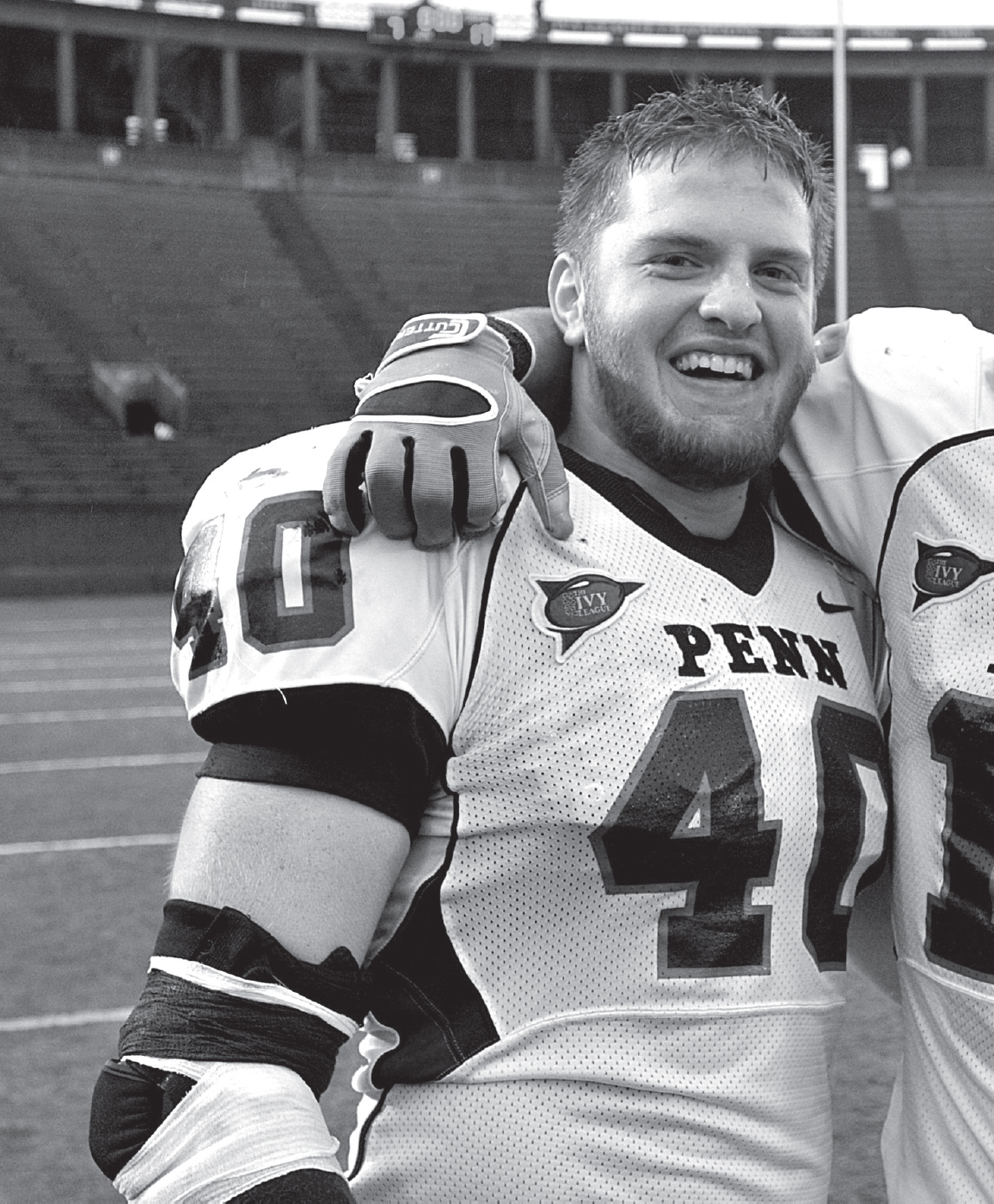

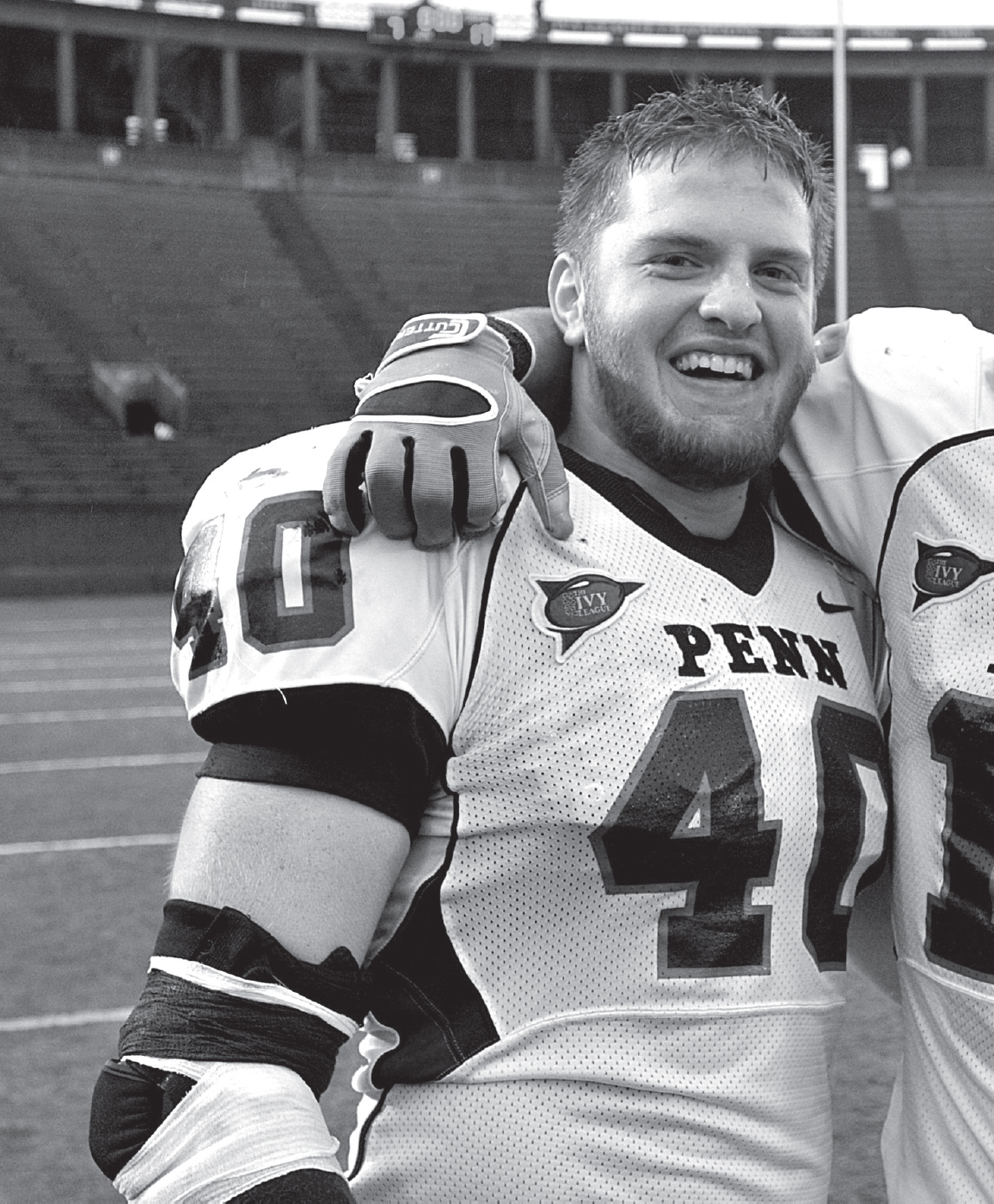

Owen Thomas after the University of Pennsylvania Quakers victory against the Crimson of Harvard University on November 14, 2009, at Harvard Stadium. (Photo Mickey Goldin)

PROLOGUE

APRIL 2010

THE BRAINS ARRIVE , usually by special courier, invariably packed in ice, to Dr. Ann McKees lab at the VA-Boston University-Concussion Legacy Foundation Brain Bank. The containers in which they are shipped could be mistaken for the ones used to ship prime steaks. Brains, however, are softer than meat in the market. More delicate, more gelatinous. Researchers pressed for a description of a brain often liken it to the popular fruit-flavored dessert that jiggles.

McKee, director of Boston Universitys CTE Center and chief neuropathologist for the Brain Bank, never forgets that they belonged to human beings, people who lived, were loved, had hopes. Most of the brains delivered to her share something in common: they belonged to people who played sports in high school or college, or professionally. Most often, they belonged to men and boys who played football.

McKee speaks freely and informally to the people who visit her office and lab. She has a directness that probably can be traced back to her Midwestern roots growing up in Wisconsin. The directness is underscored when McKee makes eye contact with her bright blue eyes. Sometimes that gaze is muted by her oversized glasses. But when a visitor comes to her office at the VA, the glasses are likely to be sitting on her desk, somewhere amid the stacks of papers and the towers of stained slides. A white lab coat covers her shirt and slacks. Shes one of the foremost researchersthe leading CTE researcher, the one most frequently associated with the disease. CTE, or chronic traumatic encephalopathy, is a progressive degenerative brain disease caused by repeated brain trauma. The trauma can be in the form of powerful blows to the head that cause concussions. It also can come from other jarring blows that cause the brain to rattle within the skull like an amusement park bumper car. Such blows are sustained by soldiers exposed to bomb blasts in combat and by football players, soccer players, hockey players, boxers. Researchers assessing traumatic brain injury in sports call this second category of trauma subconcussive hits. While such hits are not powerful enough to cause a full-blown concussion, in 2010 researchers began to realize that they were enough to do the damage that can lead to CTE.

CTE is characterized by a buildup in the brain of a protein called tau. Brains are made up of 90 billion neurons, which relay signals through long fibers called axons. When the axons are jarred, they can break, releasing toxins. Thats when a concussion occurs and with it often comes a host of symptoms: headaches, confusion, fatigue, blurred vision, problems with sleep and mood. Time and rest are required for the brain to recover.

Unlike the more obvious symptoms of concussions, which appear relatively quickly, CTE symptoms burgeon over time. Tau protein supports microtubules found in the axons, the brains signal carriers mentioned earlier. When the microtubules come apartbecause of concussions or repeated jarring blows to the headthe tau protein is dislodged and begins to clump together, breaking down communication between neurons. Eventually, brain degeneration results and the condition known as CTE can occurcausing memory loss, confusion, impaired judgment, impulse control problems, aggression, depression, and, for some, dementia. Once underway, tau buildup never stops. Insidiously, it continues to grow, even after an individual stops playing football or hockey or any other activity that may have caused the initial damage. The presence of CTE can be confirmed only after death, by researchers like Ann McKee.

McKees obsession with CTE can be traced to 2003, when she performed an autopsy on a seventy-two-year-old veteran who had been diagnosed with Alzheimers disease fifteen years earlier. Under her microscope, she saw patterns of tau protein in a totally unfamiliar pattern. There was no evidence of the beta-amyloid plaques that are present in Alzheimers patients. The veteran turned out to have been a boxer. Two years later, in 2005, the same strange pattern of tau showed up in another patient. A call to his family revealed he, too, had been a pugilist.

McKee was recruited to head CTE research at Boston University in 2008, a year after Dr. Robert Cantu, a neurologist, neurosurgeon, and leading concussion expert, and activist Chris Nowinski, PhD, founded the Sports Legacy Institute and created the centers precursor, the Boston University Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy. The institute would later become the Sports Legacy Foundation, with a goal of raising awareness about the dangers of concussions, particularly among young athletes.

No longer encased in a skull under a thatch of flaming red hair, a brain arrives at McKees lab. McKee doesnt know about the red hair. What she does know is that this was the brain of a college football player. He was in his early twenties. He committed suicide. Any more details could prejudice her work, she says.

The brain belonged to Owen Thomas.

McKees lab has detailed procedures for dealing with specimens. When Owens brain arrives, it is weighed, photographed, and visually inspected for evidence of trauma or disease. Its then preserved with periodate-lysine-paraformaldehyde, referred to as PLP, a solution preferred by McKee and her colleagues because it keeps the brain tissue a bit softer than do other preservatives used in labs. Samples are taken from twenty-eight separate areas of the brain. The rest of the brain is frozen for future investigation, while the samples are sent to histology technicians, who dehydrate them and embed them in paraffin wax. The process makes them easier to slice. The technicians use a special tool called a microtome that slices extremely thin sections of tissue for study. How thin? Thinner than you can imagine. Twenty microns. Thats the width of a human hair. The slices are mounted on slides, which are each stained from two to six times with antibodies that will reveal the target proteins that will confirm the presence of CTE.

Its late in the day when McKee turns her attention to Owens case. The late afternoon sunlight has already ceded to evening. Twilight touches the Boston streets outside. She likes working after hours, when shes the only one in the lab. A lot of times, you get into your zen of looking at the case, McKee says. Its quiet; its very meditative for me, as Im looking through the case. That night, she expects shell be able to hurry through. It should not take long with a subject this young.

In the silence of the lab, she looks at tissue from Owen Thomass frontal cortex under the microscope. She is shocked at what she sees. Repeatedly in his brain, over and over, I saw areas of abnormalities that Ive never seen except in association with CTE, McKee says.