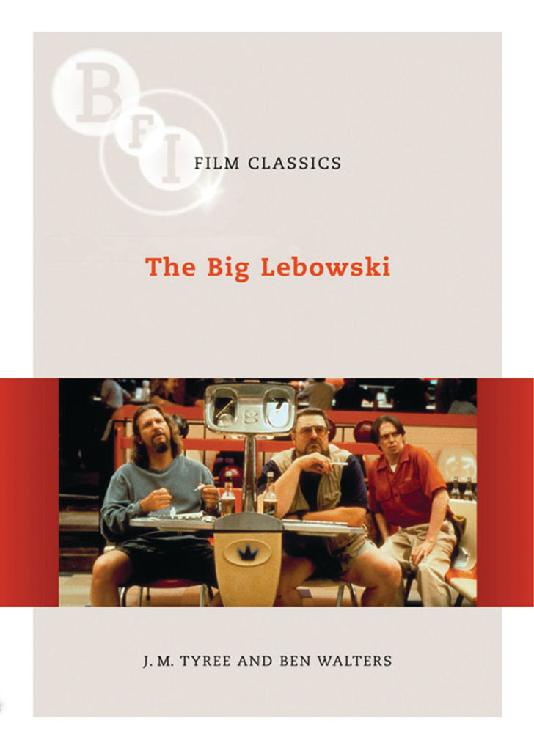

BFI Film Classics

The BFI Film Classics series introduces, interprets and celebrates landmarks of world cinema. Each volume offers an argument for the films classic status, together with discussion of its production and reception history, its place within a genre or national cinema, an account of its technical and aesthetic importance, and in many cases, the authors personal response to the film.

For a full list of titles in the series, please visit www.bloomsbury.com/uk/series/bfi-film-classics/

On 12 January 1953, the Toulouse Cine Club attempted an experiment when showing Murder, My Sweet a few weeks before the distribution rights lapsed. This involved finding out whether this film would create in the viewer that state of tension and malaise that the critics had been unanimous in describing seven years before. The experiment was negative. Marlowes third blackout, which at the time had elicited a genuine feeling of anguish, provoked a general outburst of laughter.

Raymond Borde and tienne Chaumeton,

A Panorama of American Film Noir 19411953

Contents

Since we wrote this book in 2007, The Big Lebowskis status has grown from cult to classic, featuring on most best-ever comedy (if not best-ever movie) lists and feeding ever-growing cottage industries of devoted fandom and academic analysis. The movie now has broad enough mainstream recognition for Jeff Bridges to play the Dude in a Super Bowl commercial and for a portly, laid-back incarnation of a Marvel superhero to be widely known as Lebowski Thor. The word dude slipped into Boris Johnsons victory speech during his installation as British prime minister in July 2019. We were even asked to write about the film for the United States Library of Congress, which feels pretty canonical.

And the Coens themselves have been elevated from indiearthouse darlings to bona fide Best Picture Oscar-winning industry big shots. This has happened without the bastardization of their distinctive sensibility, which both affirms their self-determined savvy and reminds us how imbricated that sensibility has always been with classical Hollywood terms.

Our working theory of the film that it is really fucking funny hasnt changed. And even if The Big Lebowski is now old enough to buy itself a White Russian, its richly layered text continues to yield new delights. We noticed only recently, for instance, how redolent the nihilists bizarre ransom delivery instructions are of a similarly complex set-up in Akira Kurosawas High & Low (1963), in which the cash is thrown from a moving train. Intentional or not, this resonance might be a droll way of indicating that the nihilists went to art school and got their ideas about how to stage a kidnapping from a vaguely remembered undergrad survey course on world cinema.

Were happy that the past decade has been kind to the Coens and Lebowski. As admirers of the Dudes nuanced, laconic, violence-averse and humane worldview, however, were dismayed that the same period has seen an upswing in polarization, conflict, simplification and othering. Big Lebowskis, not Dudes, stalk the land: sexist, racist, rich old white men fixed on rapacious and regressive notions of achievement; phony goldbrickers; human paraquats oozing toxic masculinity. It might even feel as if the revolution really is over and condolences! the bums lost.

Today, some of the movies absurdities take on a curious poignancy. Its celebration of promiscuous plurality feels even more valuable. The Dudes iconic status, including among many people younger than the movie itself, suggests an appetite for a more easeful, open and present-minded way of living post-ambition cosplay, perhaps, for a time of fraught precarity. And, for all its bombast, the Dudes friendship with Walter only grows more affecting and instructive thanks to its unstated premises of connection across difference, tolerance of shortcomings, acceptance of accountability and forgiveness of harm.

Lebowski joins rare company in cinema history, a comedy thats also a classic. Like other great comedies, it lives on not through pretension to universalism or impeccable anticipation of the norms and values of future generations but rather through its idiosyncrasy and blatant unacceptability in polite company. Somewhat in the manner of Chaplins jokes about starvation and cannibalism in The Gold Rush (1924), Lubitschs jaunty mockery of fascist war crimes in To Be or Not to Be (1942) or Kubricks slapstick vision of nuclear armageddon in Dr Strangelove (1964), the Coens cartoonishly engage everything from police brutality and the tenets of National Socialism to sex-offender registers and the nuances of preferred nomenclatures related to ethnicity and disability. All without melodrama, hand-wringing or losing a beat or, crucially, losing sight of each and every characters humanity.

If the film continues to work its magic for future audiences (one never knows), this humane consideration might be the reason. There is something cosmic about the view of a sometimes redeemable and largely lovable world that is nevertheless filled to the gills with human folly. Perhaps were just rambling again, or blathering about a bygone era filled with our own youthful enthusiasm for a great popular comedy, but The Big Lebowski still makes us laugh to beat the band. We take comfort in that.

July 2019

Whence Lebowski?

While writing this book in 2007, we wondered how the Coen brothers came up with the name Jeffrey Lebowski but couldnt find any information. In 2018, around the release of The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, Ben interviewed the Coens and asked them. Heres what they said:

| ETHAN | A neighbour. Childhood, uh |

| JOEL | Its a friend of Yeah, it was a neighbour in the little suburb we grew up in. |

| ETHAN | Didnt Jeff Lebowski Isnt he, like, attorney general of the state or something? He had some prominence. [Jeff Lebowski became General Counsel in the Minnesota Department of Labor and Industry.] |

| JOEL | Our sister, her best friend was Bonnie Lebowski. |

| ETHAN | And her brother was Jeff, right? It was Jeff? |

| JOEL | Oh, I think so. I dont know if it was her brother. I think it was a relative. Im not sure. Anyway, yeah. It comes from there. |

| ETHAN | We once complimented Paul Schrader on the end of Taxi Driver. He [Robert De Niro] gets the note from the parents to Jodie Foster and its signed Burt and Ivy Steensma and we complimented him on the name and he said, Childhood friends. |

| JOEL | My mother, when she was still alive, whenever she would beg us to stop using the names of neighbours, in our movies, and friends of theirs when we were growing up. She would Please, would you stop using? Cause we did do that constantly. Mrs Samsky [used in A Serious Man] was our next-door neighbour when we were growing up. |

| ETHAN | The studio head in Barton Fink was our rabbi, Jack Lipnick. Well, actually, Jerry Lipnick. |

Collaborative writing sharpened our ideas and doubled our luck in finding connections, tracking down sources and catching at least some of our errors. It also gave us an appreciation for the working methods of artists who, like the Coens but unlike most critics, prefer not to work alone. This book benefitted from dozens of conversations with friends, family and fans: