Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

THE WORDS OF MY FATHER

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

YOUSEF BASHIR is a Palestinian from the Gaza Strip, the son of a respected educator. After relocating to the United States, he earned a BA in International Affairs from Northeastern University and an MA in Co-existence and Conflict from Brandeis University. Now living in Washington, DC, Bashir is a public speaker, author, and peace advocate. He currently works for the Palestinian Diplomatic Delegation to the United States.

THE WORDS OF

MY FATHER

Y O U S E F K H A L I L B A S H I R

Published in 2018 by

HAUS PUBLISHING LTD

4 Cinnamon Row

London SW 11 3 TW

Copyright 2018 Yousef Bashir

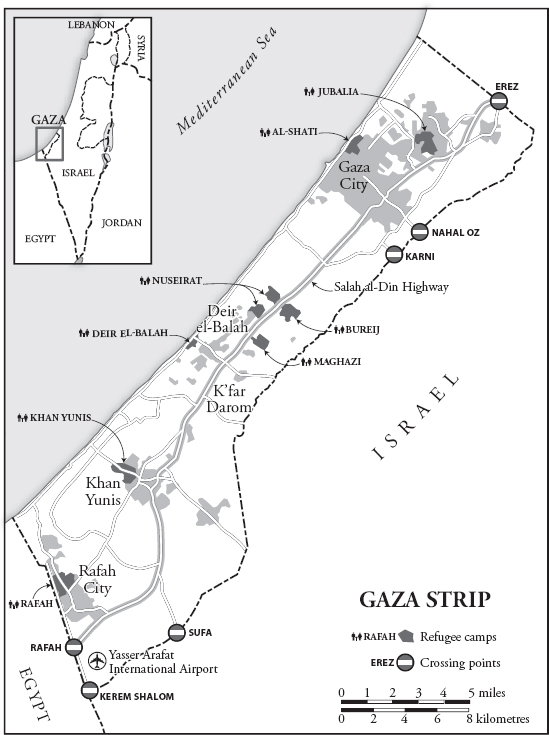

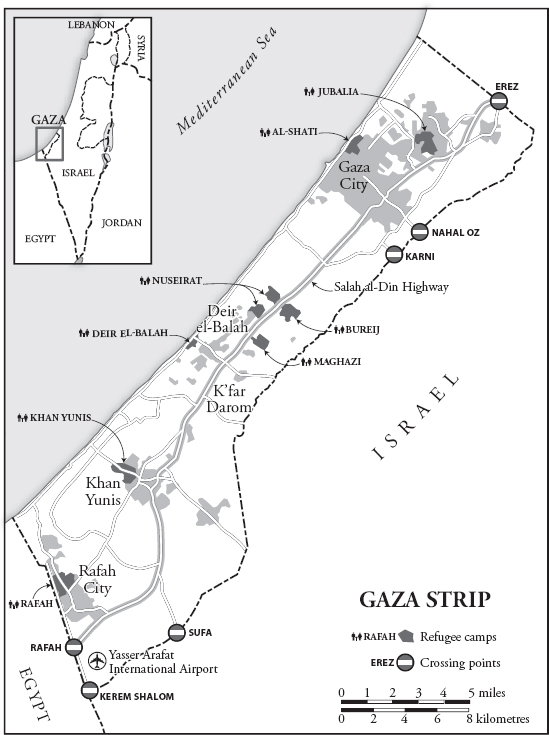

Map on p. vi created by Martin Lubikowski

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-912208-17-3

eISBN: 978-1-912208-18-0

Typeset in Garamond by MacGuru Ltd

Printed in the UK by TJ International

All rights reserved.

To my fellow Palestinians struggling for peace, justice, and freedom.

We must not let our wounded memory guide our future.

Khalil Bashir

Before I Start

I have learned to read my audiences. If there is a hush as I am led onto the stage, then I know I have already hooked them. If, however, the buzz in the room continues while someone shows me my seat and adjusts the microphone, I know they are thinking about other things and I am going to have to work a little harder.

If the room is small, like a meeting room or a classroom, I start working on eye contact right away. I suppose it is my way of announcing myself. In a large hotel function room like this one, I just scan the crowd. Some look back at me, as curious about me as I am about them. Most are checking their iPhones for important messages from friends about what they had for lunch. Others are networking. A typical Washington crowd. If I were not on the podium, I would be doing the same.

They are well dressed. These three-piece-suit people will ask questions that are heavy with facts and are more statements than questions. Students in jeans and t-shirts usually ask broader, more general questions.

An older woman comes over to me with a glass of water and makes sure I have everything I need. I do. She reviews the sessions format. Introduction. Speak for half an hour. She will give me a signal when my time is almost over. Twenty minutes of questions. I smile and thank her. I do not say that the questions will run long after the twenty minutes have ended, that when the session is over there will be a knot of people who come to the stage to ask even more and stay there long after everyone else has left the hall, or that a small group will trail me out to the lobby until they head off one by one. This happens all the time.

I look out over the audience. There are a couple of hundred of them. I presume that many, if not most, are Jews; this event is hosted by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee which more than any other entity impacts US policy towards Palestine. These people have voices that get heard in Washington. It is important that they hear me.

One of them will ask me about the Israeli settlements on Palestinian land. I have an answer for that, but perhaps they will hear me differently after I tell them my story.

Tell them your story, Yousef, I can hear my father saying. Tell them your story, then at least they will know something they did not know before.

My story is in so many ways my fathers story. My grandfathers story. And the story of so many grandfathers before him. For centuries before Europe exploded and sent its Jewish people in search of safety, my family has farmed the land along the Mediterranean coast in Gaza. Our town, Deir el-Balah, is named Monastery of the Date Palms after a monastery established there by the Christians in the 4th century CE. Even before then, it was already an important stopping point along the route to Egypt. It once had a fortress. Alexander the Great passed through, as did the Romans, the Ottomans, and probably even Joseph and his brothers.

My family, the Bashirs, watched them come and go, and maybe even sold them some of our dates. Two things had brought my ancestors to this place: fresh water springs that never ran dry, and the sweetest, reddest dates on the Mediterranean coast. We have been there forever. And for the past three hundred years since records were first kept, our name has been on them for this land.

Though my father, Khalil Bashir, was known as an English teacher in the local schools and later as a high school headmaster, our land was so much a part of his identity that he thought of himself as a farmer.

This land has been in my family for hundreds of years, I heard him say many times. It is my childhood. It is my memories. It is my family. I cannot leave, because history is watching and I am not prepared to make the same mistake my people made in May 1948 when they evacuated their homeland. This is a lesson to everybody: you must never give up your land or your country, otherwise you will lose your dignity and your life.

A well-dressed young man steps up to the podium and quiets the room. The audience put away their iPhones, at least for the moment. I will know that I am losing their attention if the phones reappear.

From the moment the young man says that I am a Palestinian, the room becomes extra quiet. It always does. I look out and smile. I can almost hear them thinking, But he looks so Jewish. Several, in fact, will say that to me afterwards. I just want to tell them now, Of course I look Jewish. We all have the same genes. The scientists have proven it. We are cousins. So why all these problems?

The young man briefly recounts my bio and mentions that I hold an MA from Brandeis University. What kind of Palestinian goes to Brandeis? some of them are thinking. I know this because I get that question all the time. I welcome their curiosity. It will make them more interested in what I have to say.

It is my time to speak. There is polite applause as I stand. For a split second, I am not sure where to begin. This always happens when I am facing a big group. I have brought some notes, which I will not actually use, but I look at them on the podium for a moment and let my fathers voice fill my mind.

Tell them your story, Yousef, I hear him say. I will do that. But first I will tell his.

I want to start by telling you two things about my father, I say. I speak quietly. My father was as much in love with his land as he was with my mother. And he loved both of them deeply.

Part One

PARADISE

Believers, eat the good things we provided you, and

thank God, if you are truly worshipping Him.

The Holy Quran, Surat Al-Bakarah (2:172)

Our Land, Our Neighbours

My father was as much in love with his land as he was with my mother. And he loved both of them deeply.

He loved the tall date palms along the edges of our farm that marked out an area larger than two football pitches. He loved his olive trees and the oil he produced from them. He loved his hives both for the bees and the amazing honey they produced pollinating his guavas, figs, and dates. He especially loved his greenhouses long tunnels of plastic stretched over metal frames. They covered almost half the land. He raised tomatoes in them, along with hot peppers, and aubergines that he sold to markets in Israel and Jordan, and sometimes Egypt. He had spent his lifetime enriching the sandy soil with compost to make it immensely productive.