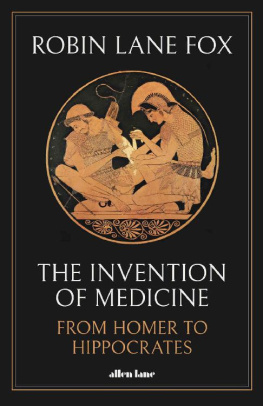

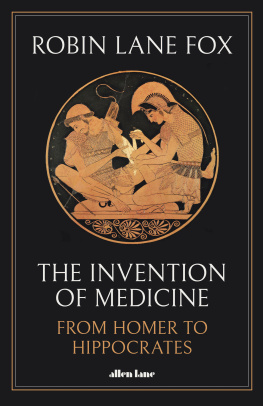

Robin Lane Fox

THE INVENTION OF MEDICINE

From Homer to Hippocrates

Contents

- PART ONE :

Heroes to Hippocrates - PART TWO :

The Doctors Island - PART THREE :

The Doctors Mind

About the Author

Robin Lane Fox is Emeritus Fellow of New College, Oxford, and taught Ancient History at Oxford University from 1977 to 2014. His books include Alexander the Great (1973), The Classical World (2005), Travelling Heroes (2008) and Augustine: Conversions to Confessions (2015) which won the Wolfson Prize for History. He has been the gardening correspondent of the Financial Times since 1970.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Alexander the Great

Pagans and Christians

The Unauthorized Version: Truth and Fiction in the Bible

The Classical World: An Epic History of Greece and Rome

Travelling Heroes: Greeks and Their Myths in the Epic Age of Homer

Thoughtful Gardening

Augustine: Conversions and Confessions

FOR LEO LANE FOX

Medicine is not only a science and an art: it is also a mode of looking at man with a compassionate objectivity. Why turn elsewhere to contemplate mans moral nature?

Owsei Temkin, The Double Face of Janus (1977), 37

The doctor sees terrible things, touches unpleasant ones and reaps a harvest of personal distress from other peoples misfortunes, whereas the sick are turned from the greatest hardships, sicknesses, distress, pain and death thanks to the [medical] craft.

Hippocratic On Breaths, c. 400 BC , 1.1

List of Illustrations

Book jacket: From an Attic red-figure shallow cup, or kylix, c. 470 BC , in which it is the tondo, or image inside on the bottom, which the drinker would see as he drank the last of his wine mixed with water. Achilles is bandaging the pained Patroclus, and an arrow, probably the source of the wound, is in the ground before him. The episode is not known in Greek poetry: it is discussed on my . An inscription states that Sosias made the cup. The painter is widely known as the Kleophrades painter, while his actual name is still uncertain. Found in the cemetery at Vulci in 1828. Now in the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung, inv. no. F 2278.

1. Doctor Iapyx fails to heal Aeneas arrow wound, while Aeneas mother, Venus, appears behind with her cocktail of healing drugs, including Cretan dittany. Aeneas son Ascanius weeps beside him, as in Virgil Aeneid XII.384424; my discusses it. Fresco-painting, c. AD 4560, from the House of P. Vedius Siricus, near the Stabian Baths in Pompeii, Ins.VII.1.25, excavated in 1851. Naples Archaeological Museum, inv. no. 9009.

2. Votive relief in the shape of a small temple, dedicated by Archinos to the healing hero Amphiaraos, at Oropos in north-east Attica, c. 360 BC . From left to right it shows three episodes of divine healing, a widespread resort for the sick from at least the later sixth century BC onwards, but the very opposite of the Hippocratic doctors medicine. The kindly hero (left) leans on his stick and attends a young patient, presumably representing Archinos, and treats his right arm, possibly with a bandage, not a knife. Behind, the right shoulder of the boy, now asleep on a couch, is being licked by a divine snake, related to the healing hero: snakes were also connected with the healing god Asclepius. Behind stands a young worshipper with his right hand raised, surely young Archinos now healed. The plaque, once painted, may have shown the item he dedicated in thanks. Amphiaraos appeared in the dreams of clients who slept in his sanctuary at night and was considered to heal them. Athens, National Archaeological Museum, inv. no. 3369.

3. Recently published fragment on papyrus of an unnamed medical text, found in the town of Oxyrhynchus in Egypt, first to second century AD . It is the first surviving reference by a Greek author to the Hippocratic Oath and to its use in the early training of medical students, but the author implies that the Oath was not used in that way by all medical teachers: for those young men who are being introduced to medicine in a reasoned way it is proper, as I see it at least, in the first place to make the beginning of learning from the Hippocratic Oath [the words are in the third line of the text] since it was established as a most just law and one which is extremely useful for life. For to those who have been initiated through it The words may belong at the beginning of a medical text. They testify to the Oaths continuing fame and its appreciation as most just. They also refer to pupils being initiated, presumably into medicine, a term used in the separate Hippocratic Law, discussed on my . P.Oxy 74.4970.

4. Sculpture of a young male, or kouros, c. 550 BC , inscribed on its right leg with the words Of Som[b]rotidas the doctor son of Mandrocles. It marked his grave. Made of marble from Naxos and imported when already cut into shape, but only partly, as its left arm is not detached from the body. The inscription is in lettering which is probably Samian. Found in the south cemetery of Megara Hyblaea, in Sicily, and discussed on my . Archaeological Museum Paolo Orsi, Syracuse, inv. no. 49401.

5. Silver tetradrachm of Abdera, c. 500475 BC . Obverse depicting a winged griffin and signature of the moneyer in the form of the first four letters of his name: PERI-. My suggest a possible link with the patient Pericles in the city. Paris, Bibliothque nationale de France, inv. no. M1694.

6. Silver drachm of Abdera, c. 475450 BC . Obverse depicting a winged griffin and signature of the moneyer in the form of the first four letters of his name: HERO-. My suggest a possible link with the patient Heropythos in the city. Heberden Coin Room, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

7. Marble grave stele, c. 480 BC , showing a bearded doctor, seated, before whom stands a youth, only partially preserved, who is holding a cupping glass in his left hand beneath a knife, probably attached to his belt. Two cupping glasses of different sizes hang on the wall between the figures, confirming the seated man to be a doctor with perhaps a young assistant, a son or a slave, before him. My favour the suggestion that he is a doctor from Cnidos. Basel, Antikenmuseum und Sammlung Ludwig, inv. no. BS 236.

8. On the left side of a major gateway into Thasos in the south-west of the citys wall, Silenus, the god Dionysuss horse-tailed companion, is sculpted striding forward with a deep drinking cup of wine in his right hand; c. 500490 BC . His left hand is held out with fingers extended as if to greet the citys residents, and his penis is massively erect, though now much worn after centuries of touching by ancient and modern hopefuls wanting the benefits of similar energy for themselves. About 2.5 metres high, this sculpture is the biggest known at this date in the Greek world. See my . Thasos city, modern Limenas.

9. Silver stater coin of Thasos, c. 510463 BC . Obverse depicting Silenus bending on one knee to carry off a maenad. His penis is erect. Her raised hand used to be read as a sign of her consent, but is now considered to be a mark to distinguish the coin-issue. The fine for each offence of flashing sexually on the roof or at the windows in one part of Thasos city was to be paid with one of these stater-coins. The Epidemic doctor will also have known and received them during his years of work in the city. See my . Classical Numismatic Group, Triton XIV, 4 January 2011, lot no. 49.

Next page