Deeply researched and featuring a colorful cast of characters out of 18th-century England... Money for Nothing is narrative history at its best, lively and fresh with new insights.

LIAQUAT AHAMED

The Hunt for Vulcan is science writing at its best... Not just learned, passionate and witty it is profoundly wise.

JUNOT DIAZ

A fresh, smartly paced account... Levenson shines a light on how science really happens.

GUARDIAN

Equal to the best science writing I've read anywhere, by any author. Beautifully written, rich in historical context... Above all great storytelling.

ALAN LIGHTMAN

Levenson's style gives life to each of the episodes of his story with good humour and a lightness of touch.

TLS

The Hunt for Vulcan includes several thrillerish elements in its style... Enthralling.

LONDON REVIEW OF BOOKS

First published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York

This is an Apollo book, first published in the UK in 2020 by Head of Zeus Ltd

Copyright Thomas Levenson, 2020

The moral right of Thomas Levenson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781784973933

Head of Zeus Ltd

First Floor East

58 Hardwick Street

London EC R RG

WWW . HEADOFZEUS . COM

the great Follies of Life

L ONDON , 1719

The year had begun well enough for Londons stock traders, working from their corner of the city, a narrow passage called Exchange Alley. Buying and selling sharesdealing not in things but in numberswas still new to the city. There was no fixed marketplace for traders in paper. So those who had mastered what was to many still a very dark art concentrated in a few taverns and inns, at Garraways, a coffeehouse that catered to the gentry, and more of them just around the corner at Jonathans, the rival coffeehouse that saw the most feverish trade in all the new ways in which it was possible to makeor be money.

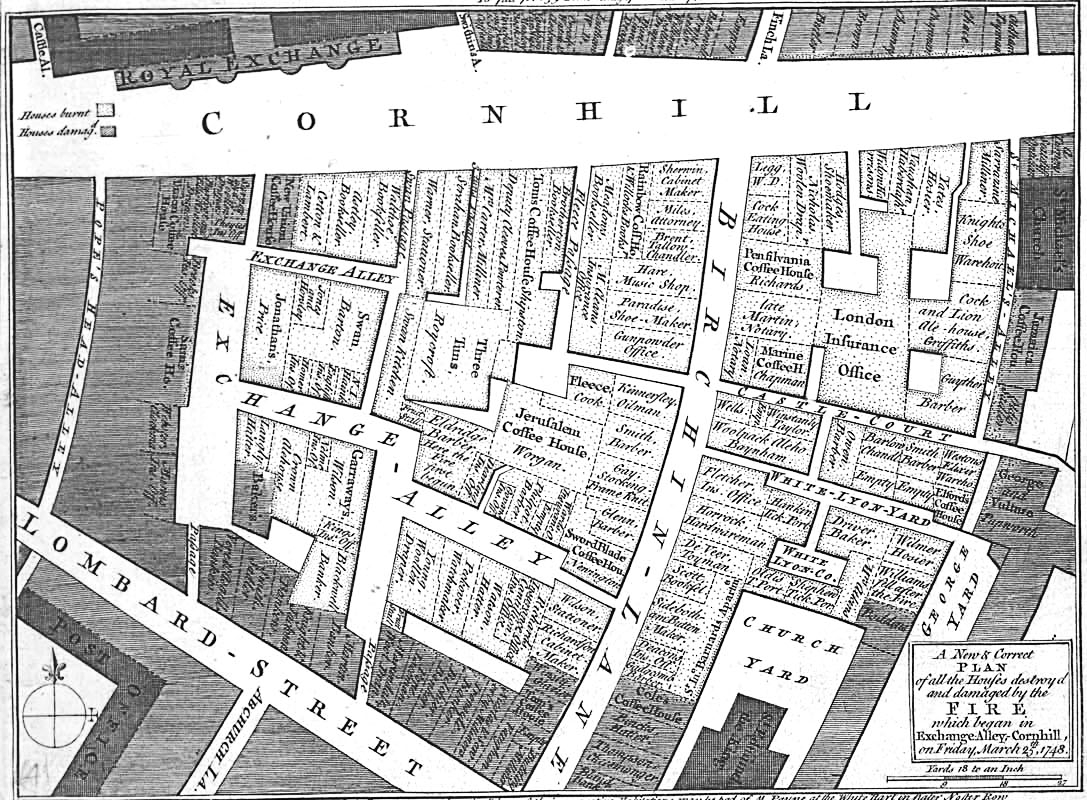

Exchange Alley in its early-eighteenth-century layout

Wikimedia Commons

For journalist, propagandist, and gadfly Daniel Defoe, Jonathans and the rest were familiarand dangerous: dens of iniquity. Defoe had been warning his fellow Britons about the perils of the Alley for almost three decades. Now, near midsummer, he was ready with his most desperate alarm yet, a pamphlet titled The Anatomy of Exchange Alley, or unlicensed dealer in stocks. In part, the pamphlet served as a kind of travel story, leading its readers on a journey to an exotic spot. Exchange Alley was an island in miniature. It could be walked in a minute or two: Stepping out of Jonathans [Coffeehouse] into the Alley, you turn your Face full South, moving on a few Paces, and then turning Due East, you advance to Garraway s; from thence going out at the other Door, you go on still East into Birchin-Lane, and then halting a little at the Sword-Blade Bank to do much Mischief in fewest Words, you immediately face to the North, enter Cornhill, visit two or three petty Provinces there in your way West. There, a few hundred paces at most, and the visitor would be almost done: Having Boxd your Compass, and saild round the whole Stock-jobbing Globe, you turn into Jonathan s again. Home again!but not in safe harbor, for the jobber concludes that as most of the great Follies of Life oblige us to do, you end just where you began.

And what folly it was! Defoe painted the risk faced by any reckless soul foolish enough to wander into Jonathans, in the tale of a navely avaricious countryman who encounters a couple of con men. They ply him with rumors, urge him to trade on their insiders knowledge, and surgically extract his entire fortune: his Coach and Horses, his fine Seat and rich Furniture, all sold to make good the Deficiency.

That was typical of Exchange Alley, Defoe warned his readers. It fostered a compleat System of Knavery a Trade founded in Fraud. Its tricks were hardly new, of course. In some form, theyre as old as human desire, as the book of Proverbs attests: , and Profit presents, to Stock-jobb [buy and sell] the Nation, couzen [trick] the Parliament, ruffle the Bank, run up and run down Stocks, and put the Dice upon the whole Town.

Stock-jobb the nation. That was the crux of Defoes polemic: schemes like this transformed the national debta public necessityinto a form that could be manipulated for private profit. That was, he argued, if not treason itself, then : Is not all that is taken from the Credit of the Publick, on such an Occasion is not every Step that is taken in Prejudice of the Kings Interest a plain constructive Treason in the Consequences of it?

In the most straightforward account of the events that were to comeknown to history as the South Sea BubbleDefoe would be proved right. In the year 1720, every Briton with two shillings to rub together, it seemed, would hear of the South Sea Company, would buy into its promises, and would be dazzled, for a time, at the prospect of riches beyond imagining. Half of Europe would too, and for a very great many it would end in ruin.

*

A ND YET , SEEN with enough distance (and a comfortable remove from those lost fortunes), its clear that Daniel Defoe was also wrong. What would happen in Exchange Alley over the next year wasnt simply the work of a Trade founded in Fraud, born of Deceit, and nourished by Trick, Cheat, Wheedle, Forgeries, Falshoods. The South Sea Bubblethe headlong rise and the sudden collapse of Londons nascent stock marketwasnt the original sin of early modern capitalismor rather, it was never only that.

Instead, as this book argues, if we are to understand the Bubble year, wider histories must come into play, ones that reach both backward and forward in time, from Defoes troubled days to our own. In this telling, the calamities of 1720 can be read as a watershed moment in the long, tangled process of creating the modern concept of money, and especially of moneys most dynamic incarnation, creditwhich makes promises expressed in numbers that connect the future to the present. The Bubble is a part of the history of finance but is not confined to it. Rather, it opens a window on the circumstances from which later financial thinking emerged: the grand shift over the preceding century in the way human beings understood their experience of the material world, an intellectual transformation better known as the scientific revolution.