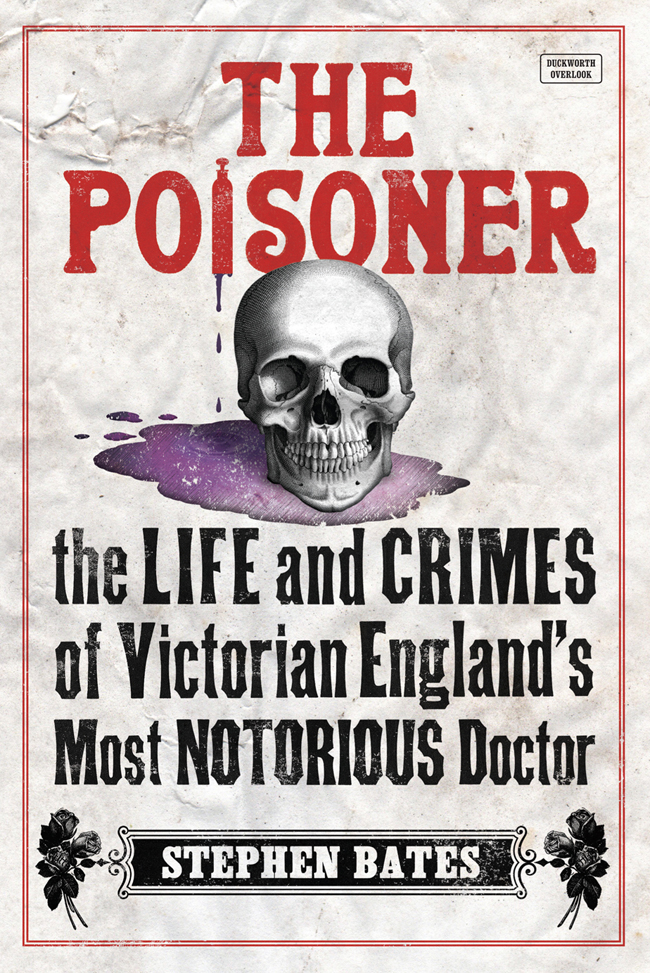

The Poisoner

OTHER BOOKS BY STEPHEN BATES

A Church at War: Anglicans and Homosexuality

Asquith

Gods Own Country: Religion and Politics in the US

The Photographers Boy: A Novel

Penny Loaves and Butter Cheap: Britain in 1846

The Poisoner

The Life and Crimes of

Victorian Englands

Most Notorious Doctor

Stephen Bates

DUCKWORTH OVERLOOK

This eBook edition 2014

First published in the UK and US in 2014 by

Duckworth Overlook

LONDON

30 Calvin Street, London E1 6NW

T: 020 7490 7300

E:

www.ducknet.co.uk

For bulk and special sales, please contact

or write to us at the address above

NEW YORK

141 Wooster Street, New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

2014 by Stephen Bates

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

The right of Stephen Bates to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBNs

UK hardback: 978-0-7156-4750-9

Kindle: 978-0-7156-4908-4

ePub: 978-0-7156-4909-1

Library PDF: 978-0-7156-4910-7

For James Meikle, who enjoys a good murder .. .

Contents

List of Illustrations

The Poisoner

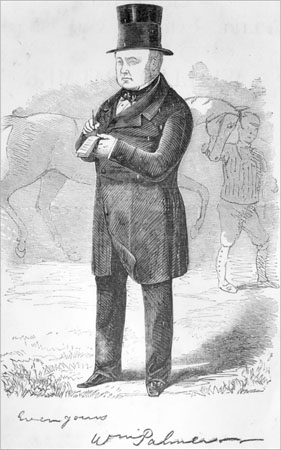

William Palmer, at the racecourse, assessing the odds, betting book in his hands and mourning band around his hat.

Stafford, 14 June 1856

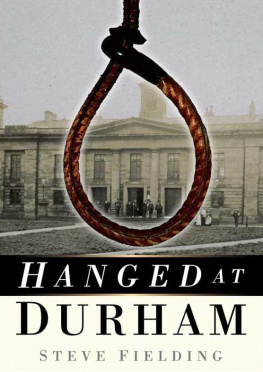

T HE NIGHT HAD BEEN UNSEASONABLY COLD AND WET FOR JUNE, BUT HOUR after hour the tramp of boots and clogs and the grind and clatter of iron-rimmed wheels could be heard down the country lanes and village streets of the Midlands. Children lying awake in their beds would never forget the sound. It seemed as if the whole world was quietly on the move through the darkness. Thousands of people, heedless of the intermittent gusts of rain, were converging on the county town of Stafford. There was to be a public hanging on the morning of one of the most notorious murderers Victorian England had ever known or read about, and they did not want to miss it. Dr William Palmer, the infamous Rugeley Poisoner, a respectable professional man from a wealthy family yet a serial killer, was going to swing for his crimes and it would be quite something to watch it would be a tale they could tell their grandchildren. Perhaps there would be an affecting scene, a breakdown, tears or, best of all, a confession and repentance: a true spectacle. That would be worth the sleepless night, the damp and the hours of walking in the pitch dark 10 miles, 20 miles some had done, then the same journey home to follow later. Why, it would be almost as good as a public holiday.

At Staffords new railway station, the excursion trains were pulling in every half-hour through the night: from Manchester and Liverpool, up from Birmingham and the industrial towns of the Black Country, Walsall and Wolverhampton, Tipton and Dudley, and across from Shrewsbury and Stoke. The passengers crowding the trains were joining the throng in the streets. They too were avid to see a man die before breakfast.

Stafford was bursting with revellers that night: the gathering crowd would swell it to at least twice its normal size. Later, it would be estimated that 30,000 spectators had been present, but no one could have done a headcount. The streets were packed and the pubs were open and doing a roaring trade as the visitors drank through the evening and into the early hours, sheltering from the rain, keeping their courage up and singing songs to while away the time. It was, said the Staffordshire Advertiser sanctimoniously in its next edition,

a miscellaneous company and occasional snatches of a Bacchanalian or a rustic song were heard as small parties moved unsteadily onwards the song being suddenly checked as the chaunters remembered where and for what they were going. Hundreds, tired, footsore and travel stained had evidently tramped many miles to reach Stafford and for five hours carriages of every kind, laden to the very extreme capacity... poured into the town in an unremitting stream... there was a complete procession of over-laden spring carts, omnibuses, many with four horses and all descriptions of vehicles. We heard one aged man boast he had walked from a place 14 miles off to see the sight and that he meant to walk back again. No doubt many others walked as far, or further, urged and supported by that indefinable, morbid taste which causes such large and miscellaneous gatherings of spectators at the execution of any criminal of peculiar notoriety.

Not everyone was drinking. Moving among the crowd were preachers and peddlers of improving tracts and ballads, men carrying placards warning of the wages of sin and others carrying Palmers last words before he had had a chance to make them and his confession before he had made that too.

Many journalists were also stalking the town that night. More than forty had been sent from the London papers, and the regional press from Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, Nottingham and many other towns and cities. The execution was a big story: the biggest of the year, bigger in column inches than the ending of the Crimean War. Even Queen Victoria had been following it: That horrible Palmer, she had written in her private journal the day after his trial, A doctor and a blackleg... everyone was convinced he had done it... the scoundrel. And the case of William Palmer was not only filling the newspapers of Britain: the New York Times had reported it the Borgia of the betting ring, it had called him, a story that outdistanced the best-selling romances of Bulwer Lytton. Even the Ballarat Star in far-off Australia had written up the story.

So great had been the expected crowd public executions always brought a rowdy mob, craning for a view and disappointed if they didnt get a spectacle that about twenty stands had been erected in the private gardens and on the roofs opposite the front of the prison where the hanging was to occur. The mayor had sent out the borough surveyor to inspect the structures sturdiness and to issue licences. Spectators would pay for such a view, even more if they could secure a place in the warm, at a window overlooking the road in front of the jail where the execution was to take place at 8 a.m. The last thing Stafford would want was a stand collapsing and crushing its occupants. They had had that once before: executions had formerly been carried out on the prison gatehouse roof, which had allowed everyone to get a good view, but the scaffold on that occasion had collapsed in mid-execution, so now there was a portable gallows and the sentence of the law was carried out only a little way above the ground. By three oclock in the morning the gallows, set on a large, black-hung box six feet high, had been wheeled into place on its four iron wheels outside the front gate. It had two stout beams, one at each end, and a cross-beam from which the rope dangled above a trap-door. Chains attached to the prison wall secured it in place.