LIBRARY OF AMERICA, a nonprofit publisher, is dedicated to publishing, and keeping in print, authoritative editions of Americas best and most significant writing. Each year the Library adds new volumes to its collection of essential works by Americas foremost novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, and statesmen.

Visit our website at www.loa.org to find out more about Library of America and to explore our popular Story of the Week and Moviegoer features.

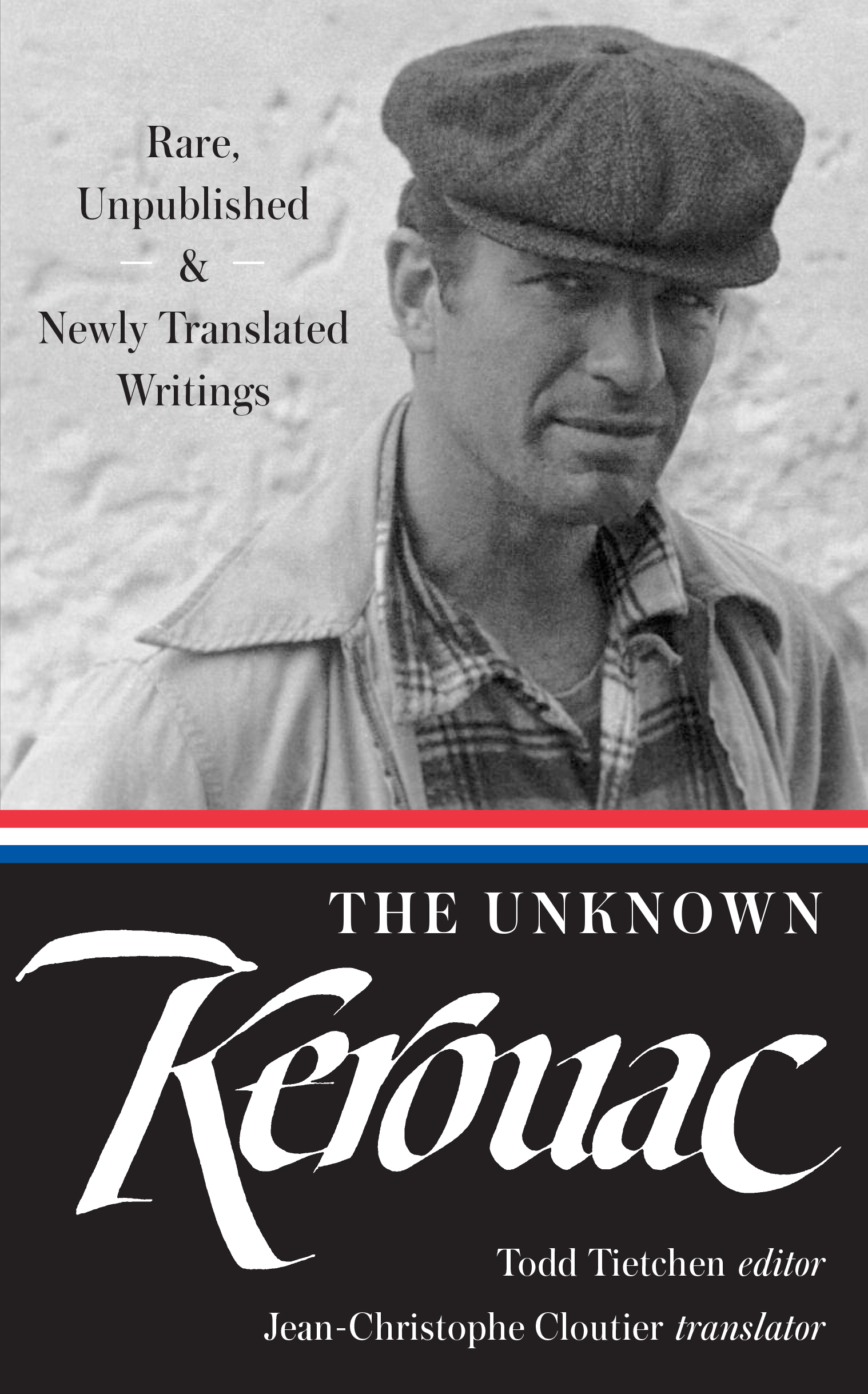

T HE writings that follow offer a substantial and vital enlargement of the Jack Kerouac canon, tracing the growth of his voice and vision and giving a fresh sense of the wellsprings of his literary art. Hitherto unexplored pieces in a moving and impressive chronicle of aesthetic development, they deepen our understanding of Kerouacs artistry and his evolution as one of the twentieth centurys most adventurous writers. These works, which span the course of Kerouacs authorial life, attest to his aspiration to become an enduring American writeran aspiration that drove him to reimagine the perspectives and cadences of American literature.

Kerouac transformed the materials of his life into a work of art realized across a multiplicity of genres and categoriesletters, journals, poetry, novelized prose, and mongrel modes of experimentation juxtaposing and blending these forms. He was a tirelessly prolific and relentlessly ambitious writer, at what often proved a significant personal cost. The writings collected in this book will become indispensable to future appreciations of Kerouacs work, prompting reconsideration of much that has been taken for granted about the intentions and scope of his accomplishment.

Many readers discover Kerouac through On the Road (1957), the signature work that seems to position its author as the generational voice of young people breaking free of their inherited past for the immensities of experiential possibility in Cold War America, hitting the road in a literal and figurative escape from crumbling moral conventions and mores. That is, in brief, the Kerouac myth. It has proven particularly hardy; and as myths are apt to do, it foregrounds one aspect of its subject at the expense of others. Kerouac himself resisted the myth. It becomes clear, for instance, from Beat Spotlightan incomplete scroll manuscript Kerouac labored over during the final year of his lifethat he came to lament the literary notoriety that followed the publication of On the Road, apprehensive that his name had become synonymous with aimlessness, irresponsibility, and criminality. Despite his dedication to the confessional and autobiographical, Kerouac died fearing that he had somehow remained unknown to critics and the reading public.

The Unknown Kerouac presents a more robust Kerouac. In the light of these newly available texts, On the Road can be seen as something more than a testament to unadulterated freedom and experiential journeying. In the wake of World War II, Sal Paradise and Dean Moriartythe novels dual protagonists based respectively on Kerouac and his close friend and muse Neal Cassadyfind themselves torn between the comforting promises of domesticity and their desire to flee conventional visions of the American good life for destinations less certain. Again and again, Sal attempts to slide out of his circumstances and into the possibilities of new experience on the road, into the new intensities that Dean heralds. Yet Sal also backtracks onto more predictable paths, into territories already settled. On the Road provides a detailed literary sketching of a generation torn between orthodoxies and unconventionalities, sentimental flirtations with nostalgia and optimistic longings for a world newly pried open.

Sal and Dean inhabit existential predicaments that Kerouac had already articulated in the holograph essays from the 1940s included here, composed while he was living in New York. Kerouac had moved to New York in 1939 from Lowell, Massachusetts, to attend Columbia University and play footballalthough his admission to Columbia required that he spend an additional year of preparatory work at the Horace Mann School. A talented athlete who also excelled in track and field and in baseball, Kerouac had harbored artistic hopes since his early teenage years. New York bohemian and jazz culture nourished those aims, as did his relationships with Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Lucien Carr, and other members of the nascent Beat orbit revolving around Columbia. In this heady environmentan environment detailed in I Wish I Were You (1945), included here as an appendixthe animating conflicts and characteristics of Kerouacs work began to take shape.

In the early essays that open this collection, Kerouac hovers somewhere between despair and triumphalism, seeking a common cultural ground with his generation while retaining his sense of being an outsider. In On Frank Sinatra, he identifies the profundity of feeling evident in the crooners voice as expressive of the mood of loneliness and longing experienced by young men during and after World War II. At times, those longings take on positive hues, as in America in World History, an affirmative essay in which Kerouac proclaims himself affiliated with his American brothers who as yet feel young and unfulfilled, poised to seek a cultural destiny distinct from the ossified traditions of Europe. Such generational optimism also infuses On Contemporary JazzBebop. Elsewhere, however, Kerouac retreats into nostalgia, as in A Couple of Facts Concerning Laws of Decadence, where couched within a critique of city intellectuals is a devotion to lineal heritage stirred by a liberal New York radio skit.

The tensions between these opposing perspectives would continue to resonate through Kerouacs writing. In the midst of his quest for the new, he often felt the pull of more familiar and consoling harbors. The allure of the quest coexists with what ultimately proves an unresolvable desire to feel rooted. Kerouacs is a literature of roots and routes. Jean-Christophe Cloutiers translations of The Night Is My Woman and Old Bull in the Bowerytwo narratives from the early 1950s originally composed in the French patois of Lowells Qubcois working class, as La nuit est ma femme and Sur le chemin respectivelybear out the crucial significance of Kerouacs roots in the French-Canadian culture of twentieth-century New England. Both works fill important gaps in Kerouacs autobiographical aesthetic, the multivolume project he outlined in his preface to Big Sur (1962) as the Duluoz Legend, greatly augmenting the ethnography of French-Canadian life contained in the Lowell trilogy consisting of