Library of America, a nonprofit organization,

champions our nations cultural heritage

by publishing Americas greatest writing in

authoritative new editions and providing resources

for readers to explore this rich, living legacy.

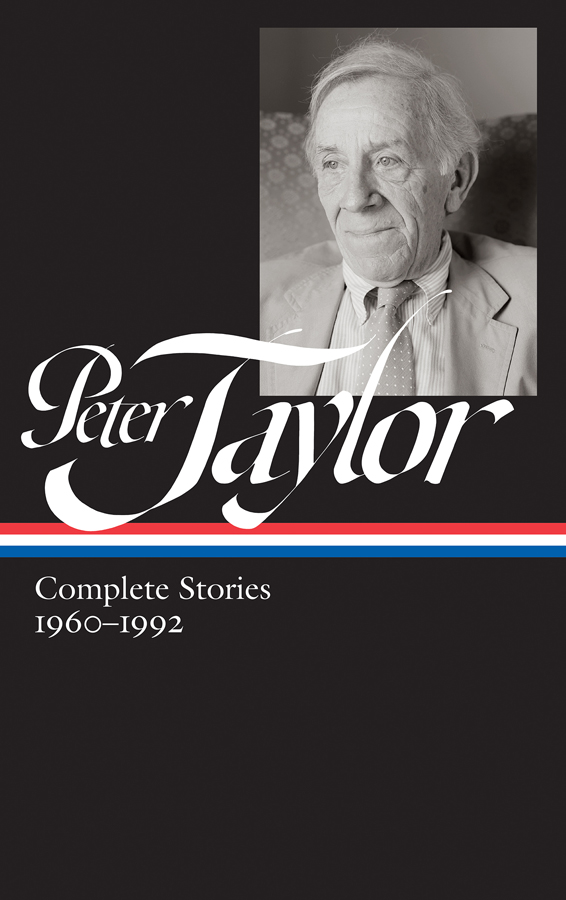

P ETER T AYLOR

COMPLETE STORIES

19601992

Ann Beattie, editor

THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA

Volume compilation, notes, and chronology copyright 2017 by

Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.

Introduction copyright 2017 by Ann Beattie.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without

the permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief

quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

All texts published by arrangement with the Estate of Peter Taylor.

Published in the United States by Library of America.

LIBRARY OF AMERICA, a nonprofit publisher,

is dedicated to publishing, and keeping in print,

authoritative editions of Americas best and most

significant writing. Each year the Library adds new

volumes to its collection of essential works by Americas

foremost novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, and statesmen.

Visit our website at www.loa.org to find out more about

The Library of America, and to sign up to receive our

occasional newsletter with exclusive interviews with

Library of America authors and editors,

and our popular Story of the Week e-mails.

ISBN 9781598535433

eISBN 9781598535693

Peter Taylor: The Complete Stories

is kept in print with a gift from

THE GEOFFREY C. HUGHES FOUNDATION

to the Guardians of American Letters Fund,

established by the Library of America

to ensure that every volume in the series

will be permanently available.

Contents

Introduction

BY ANN BEATTIE

M ATTHEW HILLSMAN TAYLOR JR ., nicknamed Pete, decided early to become simply Peter Taylor. The name has a certain directness, as well as a hint of elegance. Both qualities were also true of his writing, though his directness was reserved for energizing inanimate objects, as well as for presenting physical details. (His sidelong psychological studies, on the other hand, take time to unfold.) It was also his tendency to situate his characters within precisely rendered historical and social settings. His stories deepen, brushstroke by brushstroke, by gradual layeringby the verbal equivalent to what painters call atmospheric perspective. Their surfaces are no more to be trusted than the first ice on a lake.

Born in Trenton, Tennessee, in 1917, Taylor was a self-proclaimed mamas boy, though he said his mother never showed favoritism among her children: he had an older brother and two older sisters. She was old-fashioned, even for her day. Still, he adored her, and women were often the objects of his fictional fascination. The women in Taylors stories are capable, intelligent, if sometimes unpredictable in their eccentricities as well as in their fierce energies and abilities. Obi-Wan Kenobi wouldnt need to wish them anything: they already have the Force.

How wonderful that all the stories are now collected in two volumes in the Library of America series. A reader unfamiliar with Taylors work will here become an archaeologist; American history, especially the Upper Souths history of racial divisions and sometimes dubious harmonies, is everywhere on full display. Taylor was raised with servants. The woman who was once his fathers nurse also cared for him. Traditions were handed down, as were silver and obligation. Though he seldom writes about people determined to overturn the social order, Taylor never flinches when presenting encounters between whites and blackswhether affectionate, indifferent, or unkindand dramatizes them forthrightly.

The stories, rooted in daily life, use the quotidian as their point of departure into more complex matters. Writers have little use for the usual. Whenever a writer takes the pose that the events of his story are typical and ordinary, the reader knows that the story would not exist if this day, this moment, were not about to become exceptional. (Of course things will not go smoothly at the Misses Morkans annual dance in James Joyces The Dead.) Taylor mobilizes his characters and the plots that they create as if merely observing, as if capably invoking convention and happy to go along with it. To add to this effect, he sometimes creates a character, often a narrator, that the reader can take for a Peter Taylor stand-in: a child, a college professor, or a young man like Nat, the protagonist of The Old Forest, whose thwarted desires and covertness about tempting fate are at odds with what society condones and also with his inexperience. It is a woman who, in that particular story, turns the tables, and another womanNats fiance, Carolinewho, in the closing lines, kicks the table right out of the room, so to speak. It is one of the most amazing endings in modern fiction, with a revelation that rises out of the subtext: Though itsays Nat, referring to leaving home and rejecting an identity determined by othersclearly meant that we must live on a somewhat more modest scale and live among people of a sort she [Caroline] was not used to, and even meant leaving Memphis forever behind us, the firmness with which she supported my decision, and the look in her eyes whenever I spoke of feeling I must make the change, seemed to say to me that she would dedicate her pride of power to the power of freedom I sought.

The present tense of The Old Forest is the early 1980s, when Nat is a man in his sixties. The storys action, however, takes place in a remembered 1937, just before Nat, then a college undergraduate, is to marry Caroline. His wedding plans go astray when, while driving near Overton Park with another young woman, he has a minor car accident, after which the woman flees into the forest and disappears. The mystery of her disappearance must be solved before the marriage can take place. Nat, as narrator, has alerted us early on (no doubt so we might forget about it) that the story were about to read happened in the Memphis of long ago. It ends in an epiphany we never see play out. The futurethe now of the storyis only eloquently suggested. The story of the forty intervening years is barely, glancingly toldshocking as some of the few offered details are. Virginia Woolfs surprising use of parentheses to inform the reader of the death of Mrs. Ramsay in To the Lighthouse was stunning; Taylors narrator, who hurries through his account of family tragedies, is equally shocking, as the information he relays appears to be but a brief aside to the story he wishes to tell.

Every writer thinks hard about the best moment for a story to begin and end. Taylor does, too, but his dictionhis exquisite and equivocal choice of wordsoften suggests that beneath the surface action of the story dwells something more, something uncontainable. With pride of power comes the hint that Caroline is fiercely leonine (pride of lions) as well as heroically self-sacrificing. This, however, is projected onto her by Nat: it seemed to say to me. In other words, its worth noting that an idea has been planted, both in Nats mind and the readers, yet is unverifiable; we do not get to read the story of a lifetime that might otherwise inform us or offer a different interpretation of what were asked to understand. Elegant prose, calculated to convince, appears at storys enda literary high note, nearly one of elation, on which to conclude. But I wouldnt be sure. In retrospect, the story tells us a lot about Nat (perhaps that he can be as annoying as a gnat), who intermittently interrupts the narrative to inform us with disquisitions about the historical significance of the old forest. Its a ploy to distract our attention from all thats forming below the surface (as in the clich Miss the forest for the trees). Nat writes in the present, from the perspective of maturity. Nat knows himself, yet not entirely; he feels he must do the right thing, but does so only when prodded by Caroline, a strong woman; he is adamant that he and she must find another way, a new way, a way forward in which something is lost (Memphis, his family, and their expectations of him) but something also gained (autonomy and the ability to pursue ones passion). All this leaves the lioness a little on the sidelines, and the present-day reader might be saddened that the Caroline of 1937 understands that her only way forward is to attach herself to Nat, a manbut at the moment the story concludes, the two characters are united by the writer in their own version of triumph.